This Christmas marks the 10th edition of my astrophotography calendar, consisting of my better images from the previous 12-months, which I produce for myself and members of the family. Wow doesn’t time fly? Based on these images, I also compile a video of the images set to music, which we all watch together before seeing the actual calendar. It’s become something of an occasion and is a great way to present the images, which look wonderful on today’s smart TV’s and is fun to watch and share with the family.

THE CALENDAR

Much longer imaging times (total of more than 145 hours), re-imaging old favourites in new ways and unusual, overlooked, or difficult objects, resulted in a very good 2023 astrophotography year and perhaps the best calendar yet? The calendar for 2024 on YouTube can be viewed by clicking HERE and below is a brief overview of each image. More detailed background information and imaging details for those interested can be found in relevant blogs I posted on this website. The background music is the track Appleshine from Underworld’s album Drift.

| COVER | SH2-284: Close-up of April’s image – along the inside of the ring structure are many dark dust pillars and globules, which on the right seem to resemble a hand with a bony finger pointing inwards! | |

| JANUARY | NGC 1333: Nestled within the western area of the Perseus Molecular Cloud, some 1,100 light-years from Earth is the colourful NGC 1333 reflection nebula, one of the closest and most active star-forming regions of the night-sky. | |

| FEBRUARY | Spaghetti Nebula: Straddling the boundary of Taurus and Auriga constellations, is the giant supernova remnant (SNR) Simeis-147. The stellar explosion occurred 40,000 years ago, leaving a rapidly spinning neutron star or pulsar at the core of the now complex and the expanding SNR. | |

| MARCH | Aurora Borealis: Situated just below the Arctic Circle, Iceland is well known both for its geology and views of the Aurora Borealis, which we saw in March on the south coast near Kirkjubaejarkklaustur. | |

| APRIL | SH2-284: A star-forming region of dust and gases, sculpted by radiation and interstellar winds emanating from a young (3 to 4 million years) star cluster located near the centre. | |

| MAY | M3 Globular Cluster*: Consisting of 500,000 stars and over 11 billion years old, M3 is one of150 globular clusters that orbit around the Milky Way Galaxy. | |

| JUNE | M27 Apple Core Nebula*: A planetary nebula, consisting of a glowing shell of ionized gas ejected from a red giant star in its late stage of life to become a white dwarf. Complex hydrogen (red) and oxygen (blue) fans form around the outer regions, with a pulsar-like beam transecting the nebula. | |

| JULY | Monkey Head Nebula: Located 6,400 light years from Earth in the Orion constellation, the ‘Monkey’ is a so-called emission nebula, where new stars are being created within at a rapid rate. | |

| AUGUST | SH2-115: This widefield image contains a richness of various emission nebulae, centred around the distinctive large blue SH2-115 region. Just to the left of SH2-115 is the small but enigmatic SH2-116 a faint, blue disc thought to be a planetary nebula. | |

| SEPTEMBER | LDN-768 Black Cat Nebula: Close to M27 in the constellation of Vulpecula (“Little Fox”), is a dense region of stars broken-up by dark nebulae to create intriguing shapes. Here strung out from left-to-right, several of the dark nebulae seem to coalesce (visually) to create the form of a black cat. | |

| OCTOBER | SH2-126 Great Lacerta Nebula: On the western edge of the Milky Way in the southern part of Lacerta, is the very large but faint emission nebula SH2-126. The red filament structures stretch over 3 degrees, to the right is the Gecko Nebula, a molecular cloud associated with bright young stars. | |

| NOVEMBER | Flaming Star & Tadpoles Nebula: Two emission nebulae: dust & gas of the Flaming Star (below) combined with red ionized hydrogen gas produces a flame affect. Above, the stellar winds and radiation pressure from hot massive stars creates the Tadpoles ‘wriggling’ away from the centre. | |

| DECEMBER | M51 Whirlpool Galaxy*: As the smaller galaxy passes behind M51, joint gravitational forces are interacting, resulting in the misalignment of stars and unusually bright blue and pink areas across the Whirlpool galaxy. Their fates are inextricably linked and might eventually merge. | |

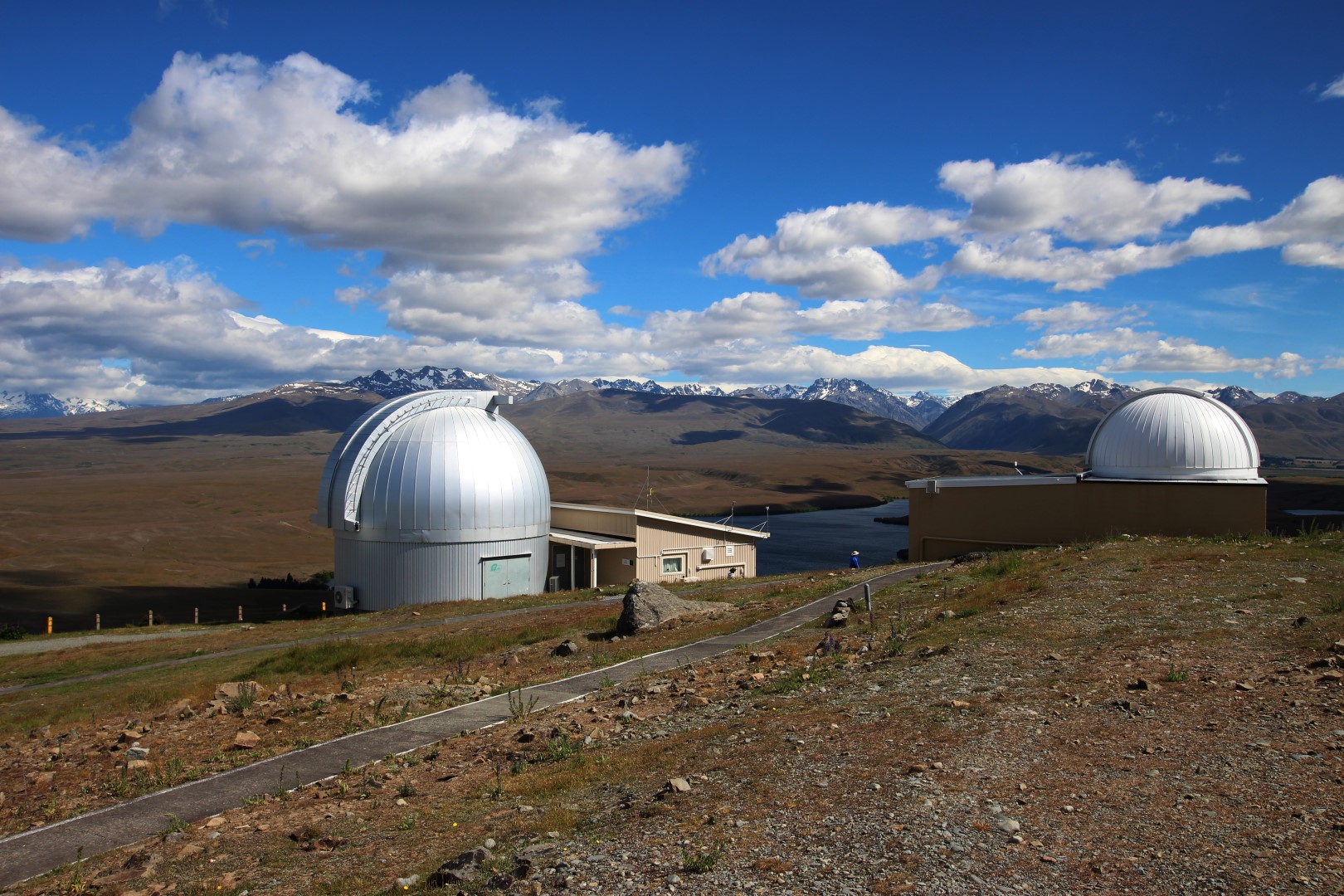

| Footnote: All images taken from Redhill, Surrey or telescope at a dark sky site in New Mexico, USA shown by an asterisk* | ||

| HAPPY NEW YEAR + CLEAR SKIES FOR 2024 | ||