The website Watch This Space (Man) began in 2015 as I started out in astronomy and is a record of my personal journey, comments and thoughts. Apart from the main blog, the website also contains links to other astrophotographers, astronomy tools, astronomy weather, and scientific papers etc., which can be accessed from the top menu.

Whilst there is a photo gallery of my work in this website, an overview of the better images can be found in the My Astrophotography FLICKR album, which can be found in the GALLERY menu. Furthermore, this year I took the plunge and joined the Astrobin community, where my images can be found using the appropriate link also in the GALLERY menu.

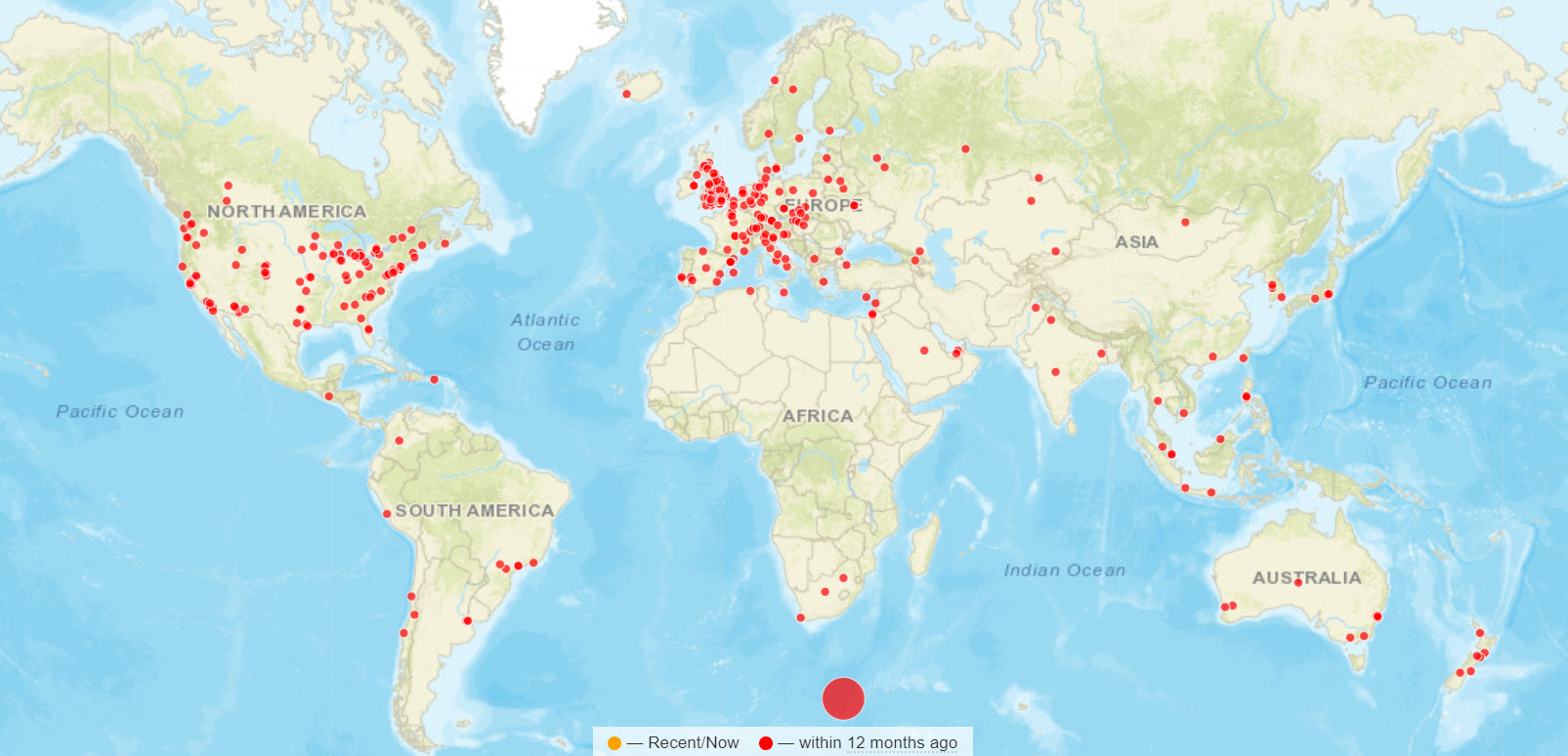

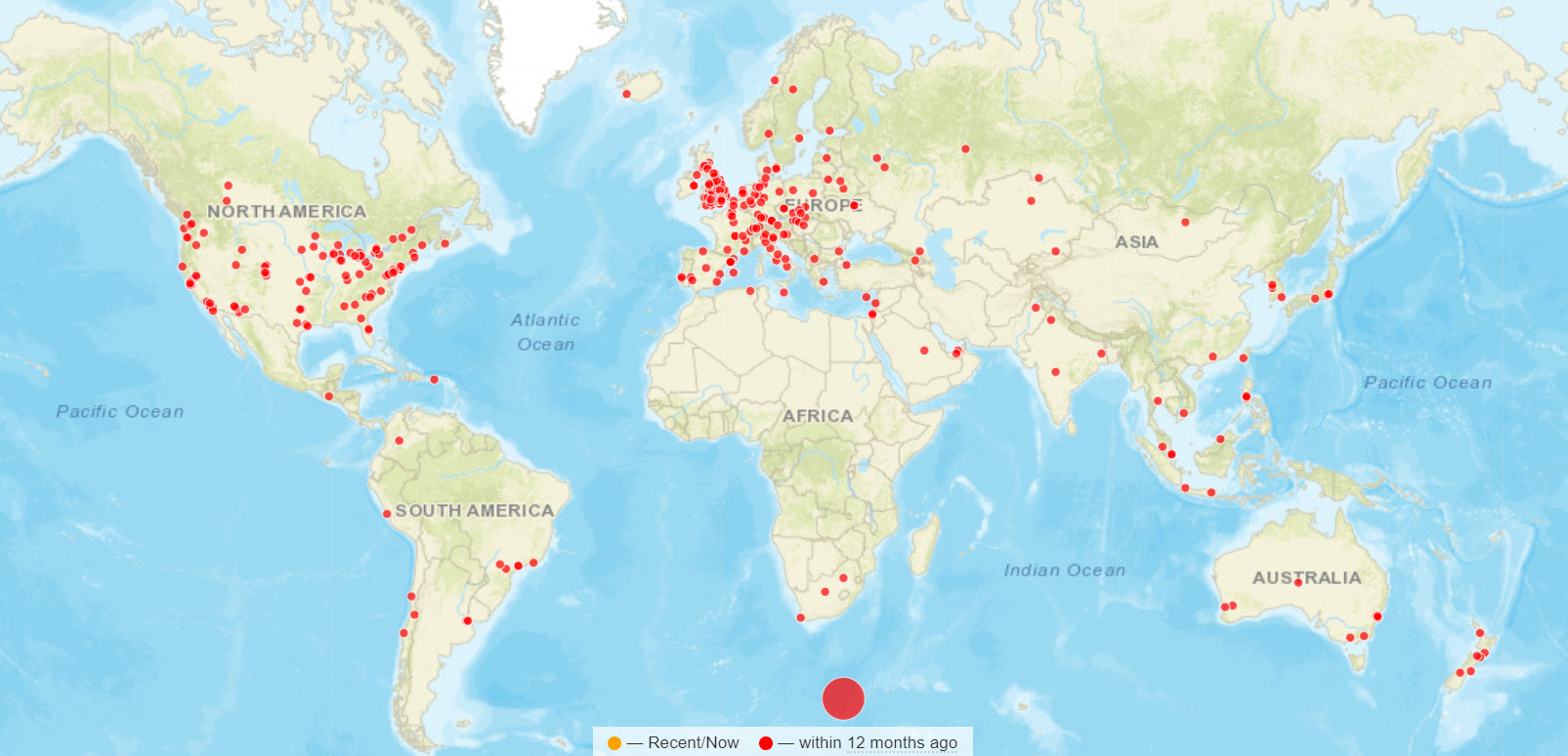

During the past year the site was visited from 64 different countries, literally from every corner of the world. I always like to hear from anybody out there – comments, questions, help or just to say hello – and can be contacted via details given in the ABOUT menu section or just leave a comment on any item if you prefer.

Reflections is compiled at the end of each year as a review of my astronomy and astrophotography during the previous twelve months, together with some thoughts on possible future developments.

Overview, Images & Goals for 2020

The past year’s plan was simple: build-on and experiment with developments from the previous year, in particular using Plate Solving to achieve longer integration times and explore further the north sky, which I could now see from the new Shed Observatory and operates during the spring and summer months.

By routinely using Plate Solving integration times, now obtained over a number of nights or even months, have increased by up to four-fold compared to previous years. As a result I concentrated on less objects but for longer time, achieving between 6 to 8 hours of subs on some occasions, the limiting factor as ever being British weather. Although quite modest compared to those able to use fixed observatories, or in clear, dry climates with Bortle 1 or 2 skies, I was very pleased with the positive impact this had on my images.

Starting astronomy and astrophotography somewhat late in the day a few years ago, like many others after retirement, the learning curve was steep and often frustrating. There were times I’ve almost considered giving up but with perseverance I’ve made progress and often get great pleasure from some of the results, as well as just enjoying and learning about this wonderful subject. For me it is just a hobby but recognising some of my achievements and abilities acquired since starting out in 2014, I was especially proud this year to be elected a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society. For all the help in reaching this point, I’d like to thank all those who have helped me from the astronomy community, wherever they are.

Favourite Images

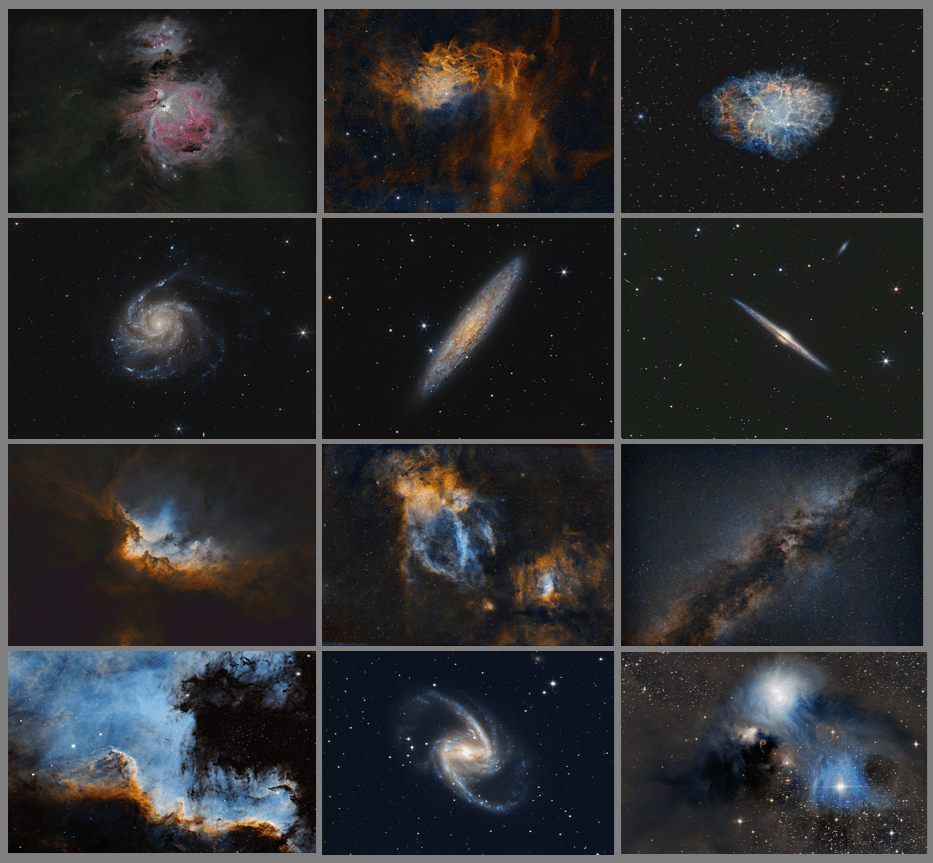

My weakness in astrophotography remains processing but having at last obtained some good integration times, this year I made a greater effort to improve these techniques – with some success. Adopting the theme less is more, I imaged just 17 different objects this year – of which nine were full narrow or broadfband images, with the rest being experimental or DSLR – with a total integration time of 65 hours (2018: 25 objects & 43 hours). The resulting images turned out well, achieving Picture of the Week on the British Astronomical Association website on six occasions. It’s therefore difficult to choose favourites from this select group based on merit alone, so this year’s favourites (see below) represent those good images that also mark a significant milestone in my astrophotography. Detailed reviews of these and all other images from 2019 are discussed in dedicated articles that can be found via the Blog Index under the ABOUT dropdown menu.

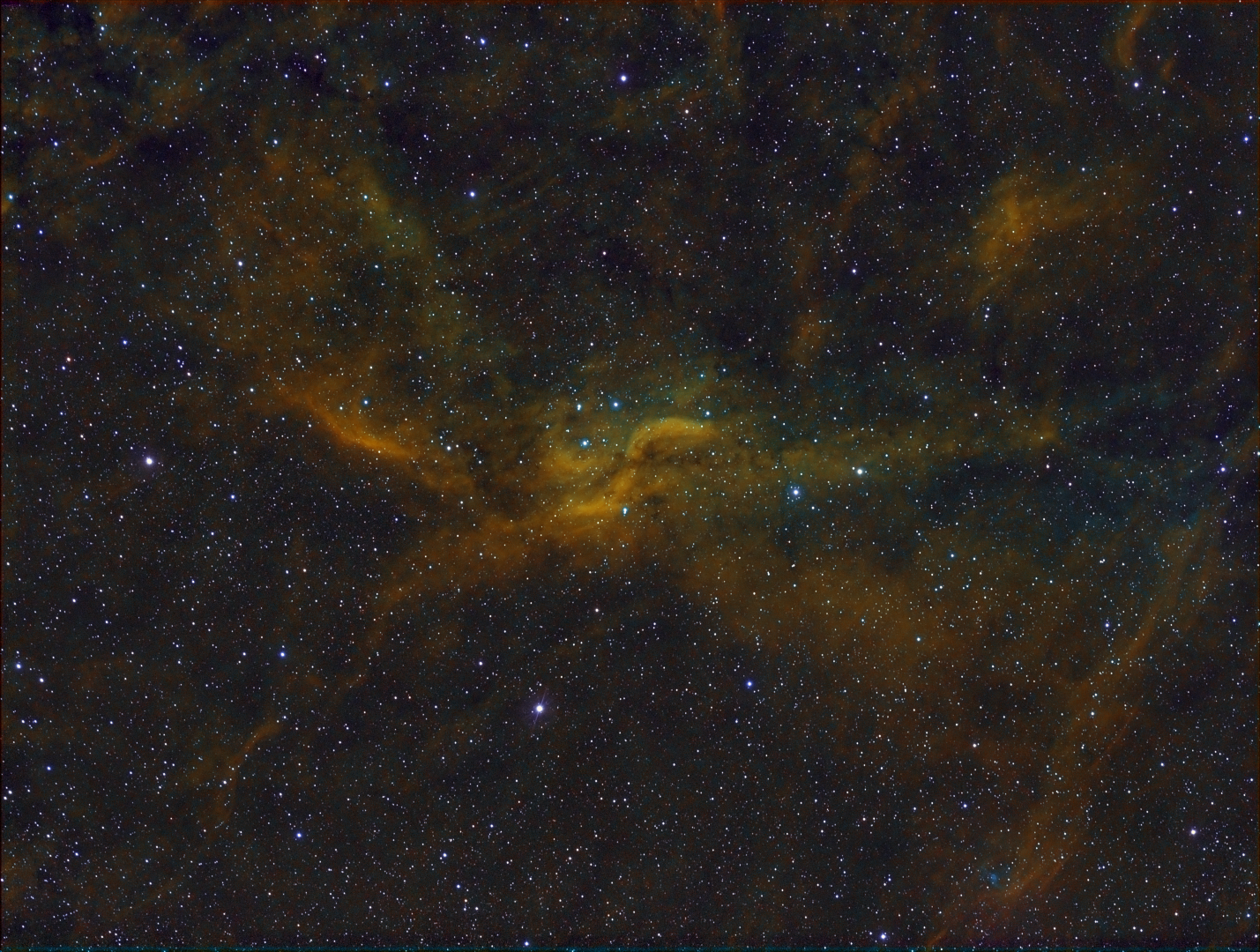

Horsehead & Flame Nebula: Usually imaged in LRGB broadband, this narrowband SHO version produced a very different affect and colours, whilst also showing the beauty of the accompanying clouds of interstellar gas and dust. Taken over three nights, at nearly 7-hours, this image was also one of my longest integration times to date.

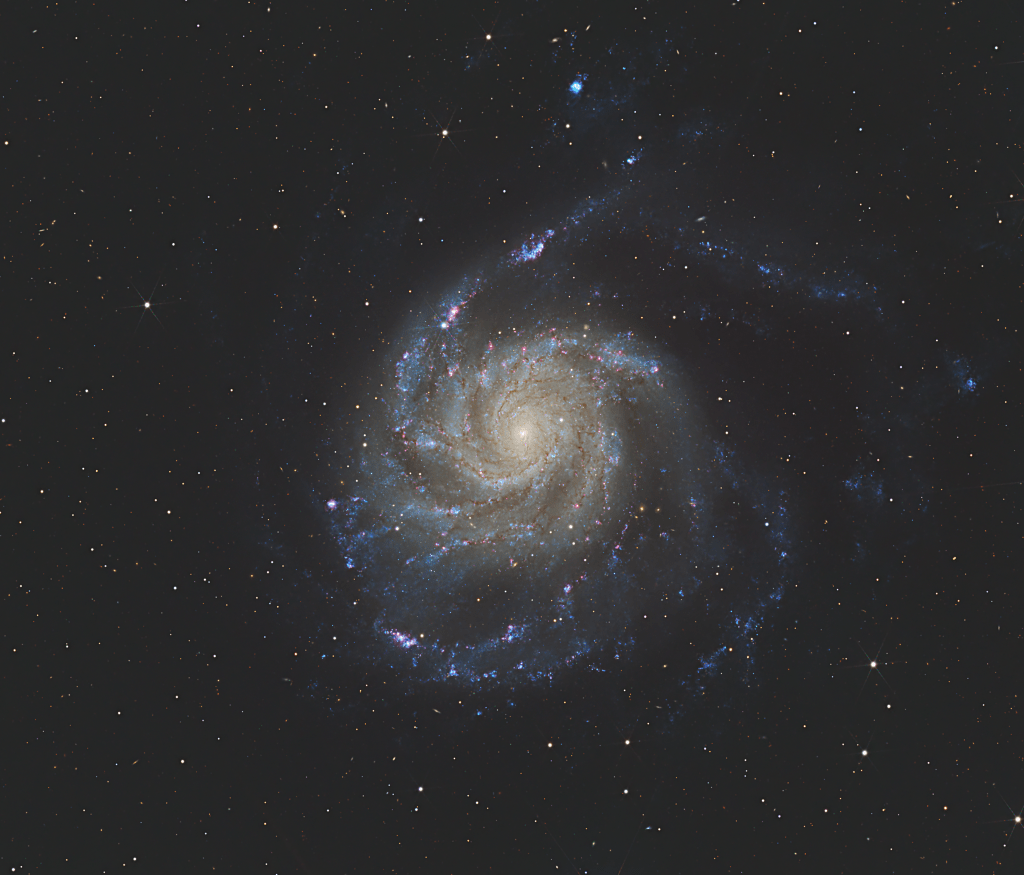

M101 Pinwheel Galaxy: Given Bortle 5-6 skies, being on the Gatwick Airport flightpath and a using a small refractor, I struggle to image galaxies and often LRGB images in general from Fairvale Observatory. However, on this occasion the combination of 5-hours HaLRGB subs and new processing techniques to enhance the colours, M101 proved the exception and is perhaps my first decent classic spiral galaxy imaged from home. Moreover, the HII regions light up along the spiral arms with the addition of Ha wavelength, producing a dazzling and dynamic image.

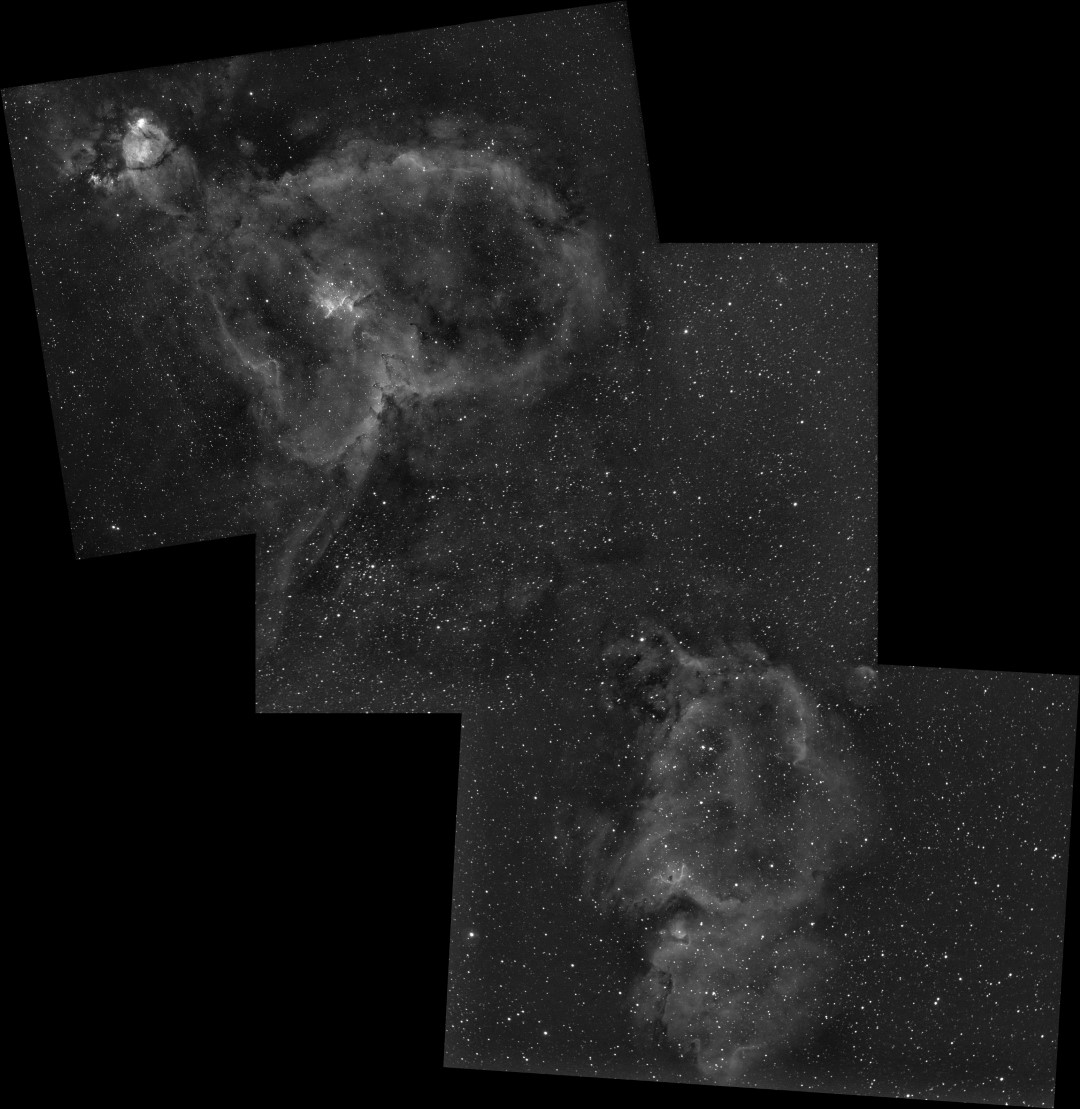

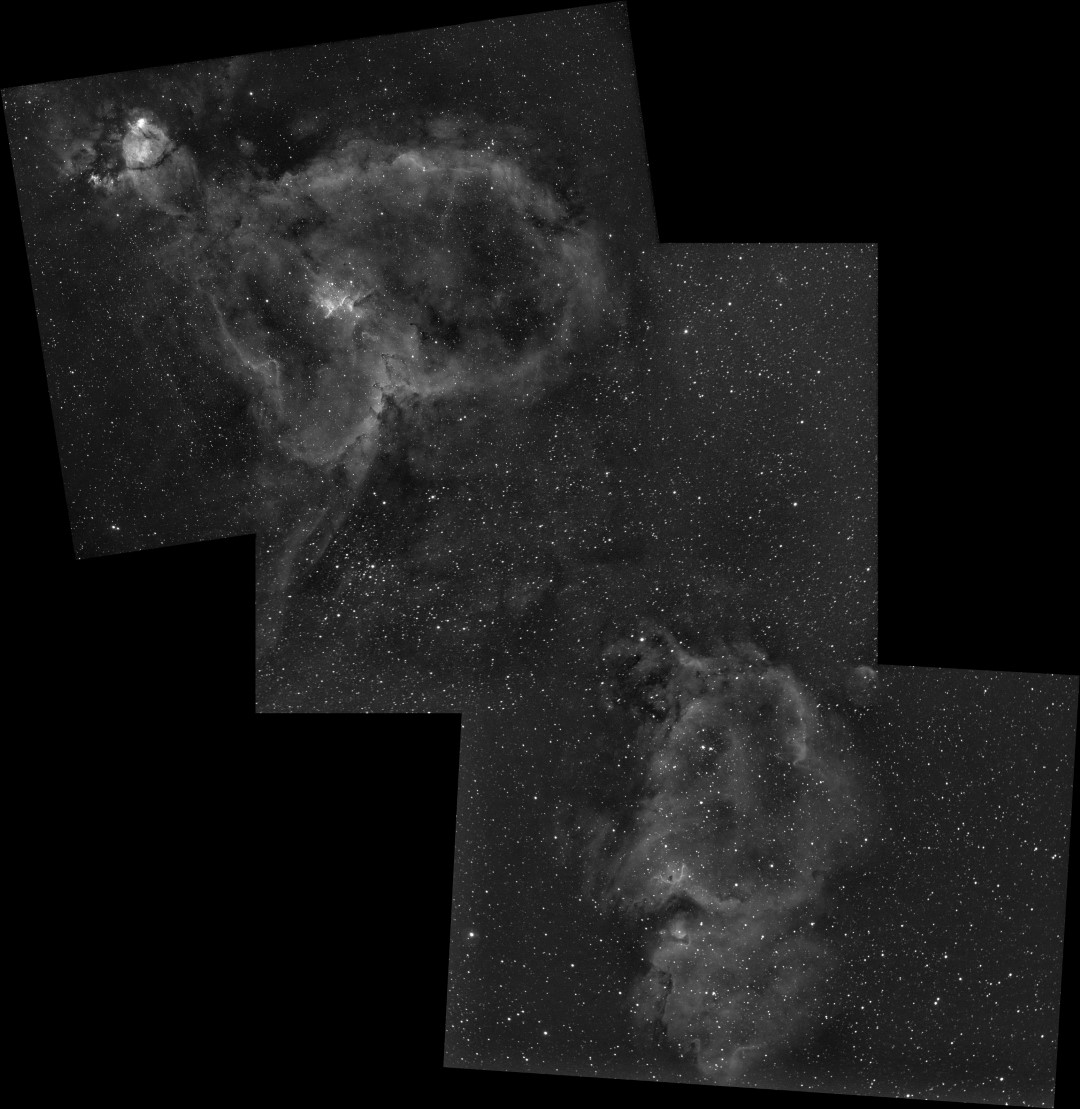

Heart & Soul Nebula: Combining existing data from 2018 of the Heart Nebula and new 2019 data of the Soul Nebula + the intervening space, this is my first albeit modest mosaic, which promises to open up significant possibilities in the future.

| RECORD CARD – 2019 |

| Goal |

Specifics / Results |

Outcome |

| Improve broadband and narrowband imaging

|

Achieved major increase of image integration times and overall quality. |

MUCH, MUCH BETTER

|

| Improve processing |

Continuing to make slow improvements, with greater use of new Photoshop techniques. |

BETTER

|

| Expand & Improve Widefield Imaging |

Despite some good images of the Milky Way in the USA, I never used the Vixen Polarie tracking mount and did not make it to any other dark sky sites = disappointing. |

FAILED

|

My objectives in 2019 mostly went well in (see above), so here goes for 2020:

- Imaging: There’s always scope to improve imaging techniques but probably most of all I still need to improve guiding quality and increase exposure and image integration times even further.

- Mosaic: Expand the use of mosaic imaging using Plate Solving and new CdC planning software.

- Improve processing: I expect this will continue to be something of a challenge for some time to come unless I go to the dark side and adopt software such as PixInsight & / or APP.

- New Observatory: Unfortunately this will not be a fixed obsy whilst I continue to live here at Fairvale which is unsuitable. However, I’m hopeful that another location between the Main (North) Observatory and the Shed Observatory might open up the north sky better and by getting away from the high hedges that surround the garden allow longer imaging sessions than can be currently obtained at the Shed.

- Other: My mind is always thinking about larger telescopes or a dual rig and / or a new high-end encoded mount but probably not until I make further progress with the above goals and / or move to a better dark sky location – dreaming is part of astrophotography = watch this space!

Although you never know, I don’t see any major breakthroughs in the coming year but more of the same – revisiting familiar objects in order to obtain new image versions based on greater integration time and hopefully using mosaic techniques to build-out images in order to encompass wider areas of the sky. This year I was surprised to discover objects that I had hitherto considered out of reach from my location (M101, M51 etc.), as well as exciting features that were completely new to me and still hold great promise e.g. DWB 111 AKA the Propeller Nebula.

Looking back I’m very happy to say 2019 was an excellent year for astronomy and astrophotography, almost certainly my best yet. You can’t ask for more than that and I hope that WTSM’s Reflections 2020 will record further such success.

Watch this space!

2019 CHRONICLE

Below is a quarter by quarter summary of my astronomy and astrophotography for the year, followed by an imaging record.

JANUARY TO MARCH

Towards the end of 2018 I decided to undertake a project, with the prime objective to gather a much longer period of integration than hitherto achieved by using my newly developed skill of Plate Solving. I’d previously imaged the Horsehead and Flame Nebula in the more traditional colour palette, either with a modded DSLR or by LRGB broadband. However, I’d recently seen this iconic image undertaken using the Hubble Palette to great affect and was inspired to do the same myself. Thereafter, for more than 2-months the clouds rolled in and I thought my project would then be impossible, not least because by now Orion had crossed the Meridian in the early evening and imaging times were at best limited. But as is often the case with astrophotography everything suddenly changed and it was game on!

The first evening of clear skies since 11th November 2018 coincided with the full lunar eclipse on 21st January, which I was therefore able to image once again. Then six days later a very untypical clear and quite warm period of weather arrived and I was able to complete my intended project after all, with further time to image both the Great Orion Nebula and the reflection nebula M78 + Barnard’s Loop (see images below).

Achieving much longer integration times of between 5 and nearly 8-hours, the impact on the resulting images was transformative. I was especially pleased with the outcome of the Horsehead project in SHO (see Favourites Images section) but found the Ha-only starless version of the same scene (see below) particularly mesmerising, as the large HII structures throughout this region bring the image to life.

By the end of February the night sky at 51o latitude has moved inexorably on to the so-called Galaxy Season, which provides something of a dearth of imaging opportunities for my 81mm telescope. However, with a good patch of weather at the end of March, whilst experimenting with the Leo Group I noticed that small areas of Ursa Major region could be seen directly above for a couple of hours, which to my surprise opened up a whole new world of possibilities hitherto considered unavailable. Shortly after I managed to obtain almost 5-hours of data on M101 the Pinwheel Galaxy, which is one of my best galaxy images taken from Fairvale Observatory (see Favourite Images section).

APRIL TO JUNE

Having discovered the albeit limited possibilities of seeing Ursa Major, I moved to the Shed Observatory early in April, which by then afforded slightly better views of the same area of sky and thereby to my great joy provided the possibility of imaging the wonderful Whirlpool Galaxy, M51. Unfortunately time was somewhat limited but it was better than nothing and I was thrilled to obtain an image of this wonderful object for the first time. Weather permitting I’ll be back for more data in 2020 with which to build on the promising result obtained this year.

By the end of April just 8-weeks away from the summer solstice astronomical darkness is in short supply. Fortunately having moved earlier to the Shed Observatory this year, I was in a good position to return to inaging the Bodes and Cigar Galaxies (see below), which had been my first ever image of north sky objects in 2018.

JULY TO SEPTEMBER

From May until late July the absence of Astronomical darkness makes astronomy difficult and frankly having progressed from the time of being a beginner, it is quite refreshing to take a break. Therefore it was only after an evening viewing the partial eclipse on 16th July and a brief experiment with the Wizzard Nebula (something for the future) at the beginning of August, that much later I returned to astrophotography seriously.

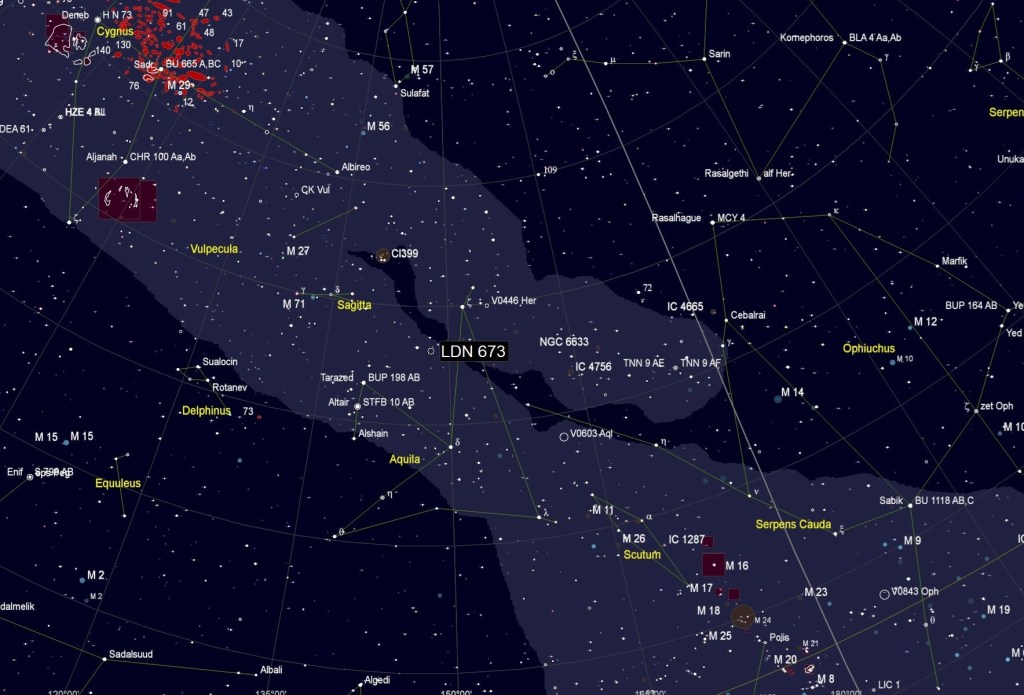

Having messed up imaging the Soul Nebula with poor framing in 2018 and being at the Shed Observatory, I decided to re-image the Soul properly, together with some of the adjacent sky in order to combine the new data with last year’s adjacent Heart Nebula to form a mosaic of both objects. I don’t know why but this was my first attempt at a mosaic. Only very recently has integrated software for mosaic planning combining Cartes de Ciel and Astrophotography Tool for image capture has been released. However, on this occasion I planned and implemented the said mosaic imaging manually, with a satisfying outcome (see Favourite Images section) but with the new software now available I hope to embark on more extensive mosaic projects in the near future.

This year’s astrophotography has followed two themes, the aforementioned ‘less is more’ with the aim of producing better images using much greater integration times. The second has been largely determined by chance, being the discovery of new objects that had hitherto either been unknown to me or considered to be out of view from Fairvale Observatory; the combination of my house, very high hedges + trees and adjacent houses obscures large swathes of the night sky. Earlier in the year such chance had led me to the M101 and M51 galaxies and in the autumn it was first the iconic Pacman Nebula and then an exciting area of Cygnus constellation.

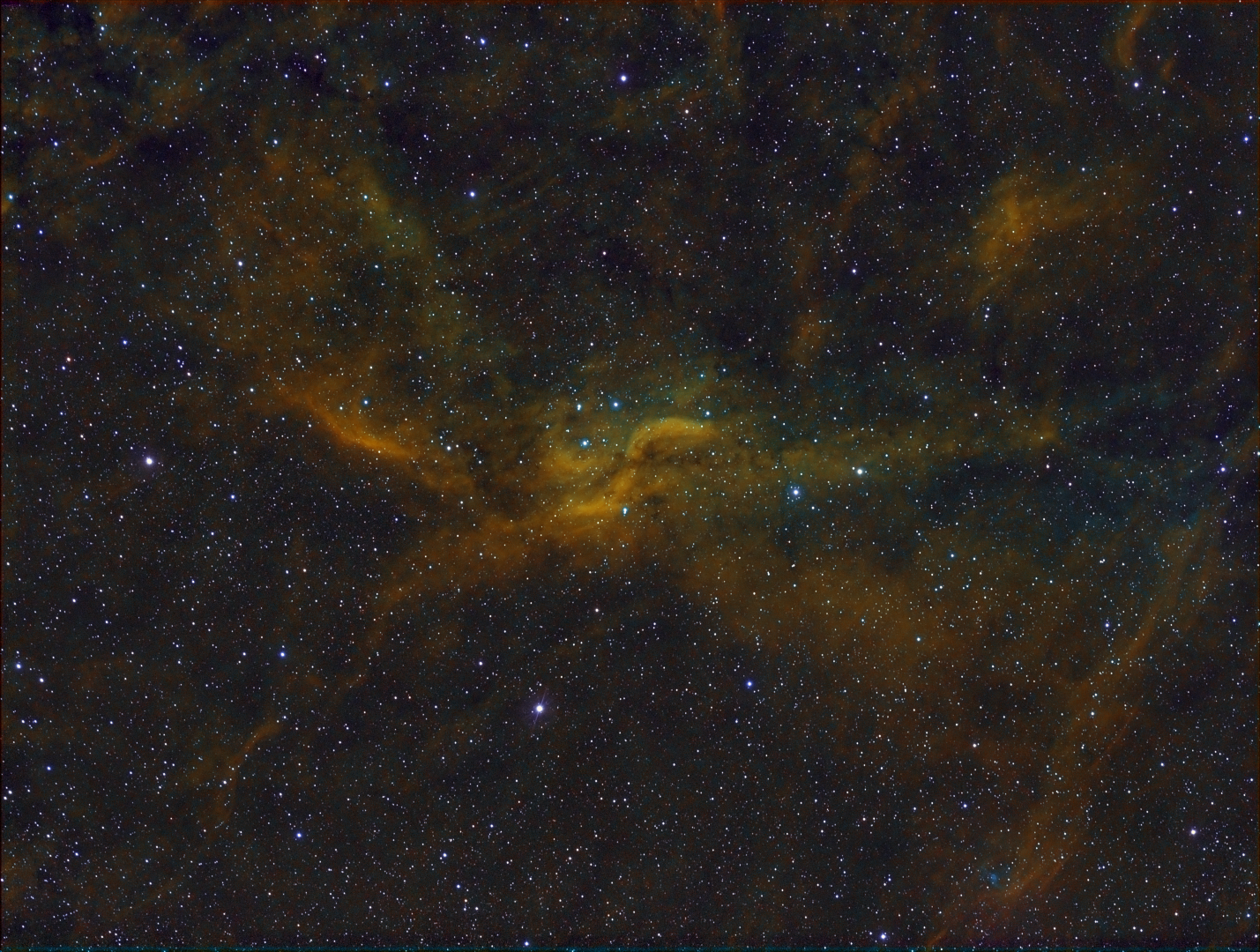

Pacman is not particularly large for my equipment but nevertheless produced a decent narrowband image, my last from the Shed Observatory for this year. Not until late September did the clouds again relent for my next project that initially seemed something of a long shot but actually turned out very well. The Propeller Nebula is located in a vast HII region of the Cygnus Constellation, which from my point-of-view was a complete surprise. At some 25 arc seconds the nebula is again on the small side for my equipment but the complexity of the adjacent HII region transforms the wider image into something really spectacular (SHO version below), which I certainly intend to visit again next year to build on the current data and explore further afield the HII region which presents exciting possibilities.

A subsequent long trip to the USA stopped all astronomy in Surrey but a couple of evenings out in Wyoming and Utah produced some incredible dark skies and DSLR Milky Way images (see below). Despite the remoteness of Spilt Mountain in the UTAH section of the Dinosaur National Monument – designated a Dark Sky Area – whilst imaging at 20 second exposures only one-in-ten images were without a plane track, very sad.

OCTOBER TO DECEMBER

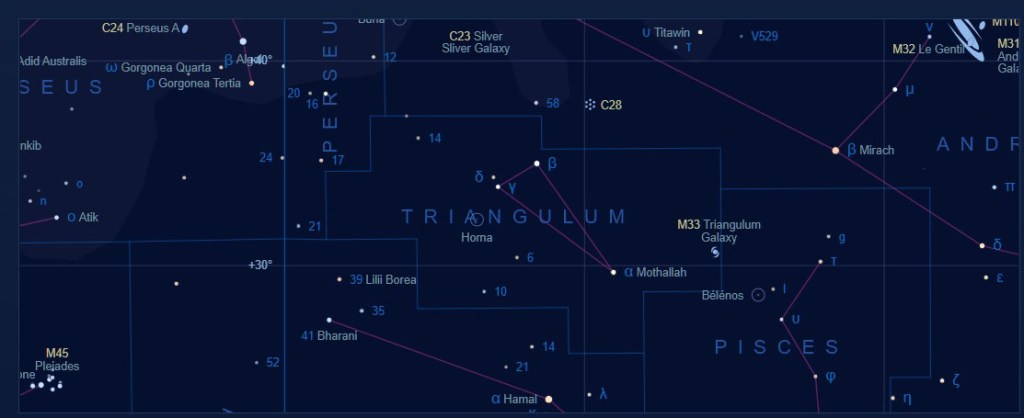

Prior to the arrival of Orion and other fun objects of the mid-winter night skies, imaging opportunities are sparse with my equipment but it’s been a couple of years since I last imaged M31 the Andromeda Galaxy and therefore for two evenings in late October it was time to give our neighbour the extended integration treatment. At 7½ hours data acquisition went well but although the processed image is probably my best yet of this object, there’s room for improvement, which I suspect will require a move to more advanced processing software?

ASTROMINAGING RECORD 2019

| No |

Date |

Type |

Object |

Name |

| |

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

21/01/19 |

DSLR |

Full Lunar Eclipse |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| 2 |

27/01/19* |

NB |

Barnard-33 &

NGC 2024 |

Horsehead & Flame Nebula |

| |

|

|

|

|

| 3 |

23/02/19* |

Combo |

M42 |

Great Orion Nebula |

| |

|

|

|

|

| 4 |

25/02/19* |

Combo |

M78 |

Reflection Nebula Orion |

| |

|

|

|

|

| 5 |

12/03/19 |

BB |

NGC443/444 |

Jellyfish Nebula |

| |

|

|

|

|

| 6 |

24/03/19 |

Combo |

M95/96/105 |

Leo-1 Group |

| |

|

|

|

|

| 7 |

29/03/19* |

Combo |

M101 |

Pinwheel Galaxy |

| |

|

|

|

|

| 8 |

10/04/19 |

Combo |

M51 |

Whirlpool Galaxy |

| |

|

|

|

|

| 9 |

13/04/19 |

BB |

M81 & m82 |

Bodes & Cigar Galaxies |

| |

|

|

|

|

| 10 |

16/07/19 |

DSLR |

Partial Lunar Eclipse |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| 11 |

02/08/19 |

NB |

NGC 7380 |

Wizzard Nebula |

| |

|

|

|

|

| 12 |

23/08/19* |

BB |

IC 1848 |

Soul Nebula +

Mosaic Link |

| |

|

|

|

|

| 13 |

26/08/19 |

NB |

NGC 281 |

PacMan Nebula |

| |

|

|

|

|

| 14 |

05/09/19* |

NB |

DWB 111 |

Propeller Nebula |

| |

|

|

|

|

| 15 |

Sept |

DSLR |

Milky Way |

Split Mountain Utah |

| |

|

|

|

|

| 16 |

22/10/19* |

Combo |

M31 |

Andromeda Galaxy |

| |

|

|

|

|

| 17 |

18/11/19 |

BB |

M74 |

Galaxy |

| |

|

|

|

|

| 18 |

18/11/18 |

NB |

SH2-240 |

Spaghetti Nebula |

| |

|

|

|

|

*multiple evenings Combo = HaLRGB Underlined = BAA published

POSTSCRIPT

The ones that got away – imaged but not seen in WTSM this year – warts and all

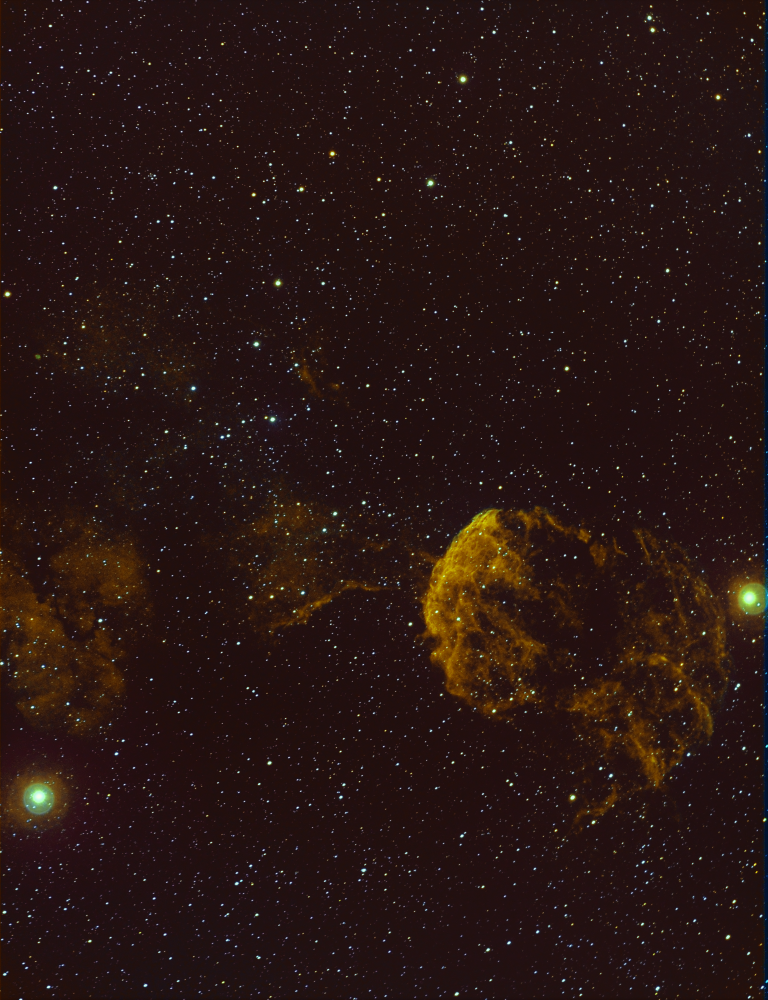

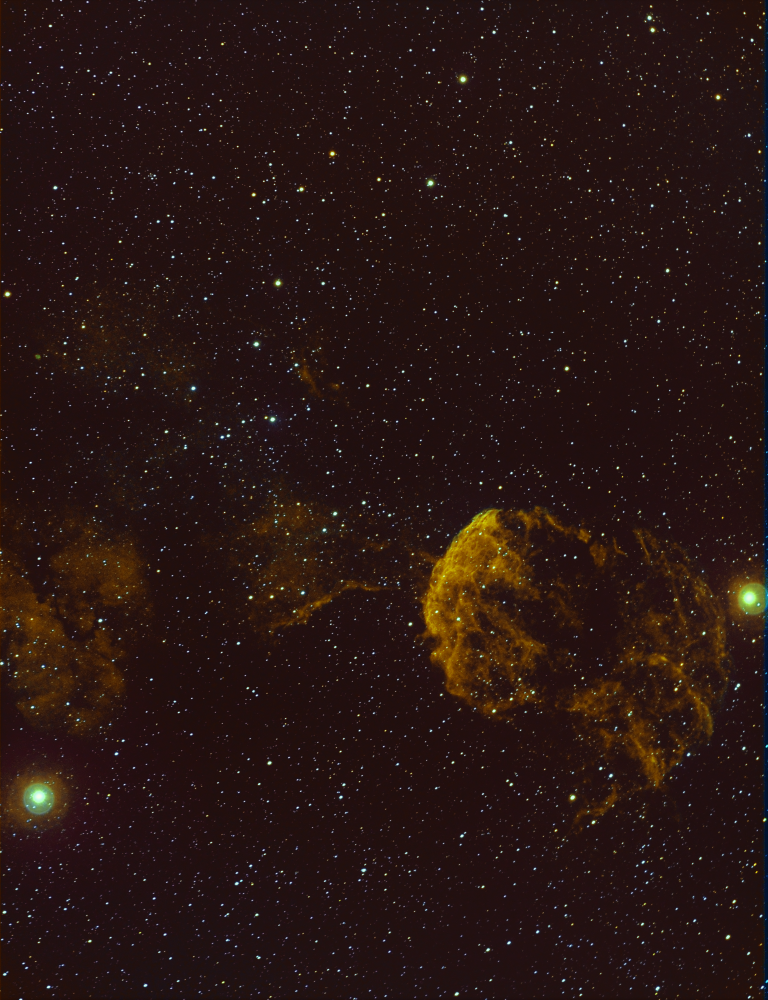

I saw some wonderful narrowband versions of the supernova remnant IC 443 Jellyfish Nebula this year, in particular adopting a wider view to incoporate its sentinel-like parner stars Tejat (Mu Geminorum) left and the tripple star Propus (Eta Geminorum) right, together with the reflection nebula IC 444 in the background. As an experiment I think it may hold promise but will require a lot more integration time to improve the quality, colour and bring out more of IC 444.

I’ve tried the Leo-1 group (M95/96/105) before but, as they say, if you don’t succeed try again. Unfortunately the passage of time didn’t help – I need a larger telescope to do these critters justice!

Dinosaur National Monument – Split Mountain, Utah. Even at this wonderfully remote location, which is one of the darkest places in the USA, passing planes still get in the way of a good image – just like at Fairvale Observatory!

At <=10 arc minutes the spiral galaxy M74 is too much for my equipment.

Located between the constellations Auriga and Gemini, SH2-240, Simeis 147 AKA the Spaghetti Nebula is a very large (+3 degrees) supernova remnant but it’s very low brightness makes imaging extremely difficult. In fact prior to and during capture in Ha-wavelength, I had no idea if it was even within the image frame. Aggressive stretching shows that it was there but only much darker skies and probably longer exposure time is likely to produce a more viable picture.

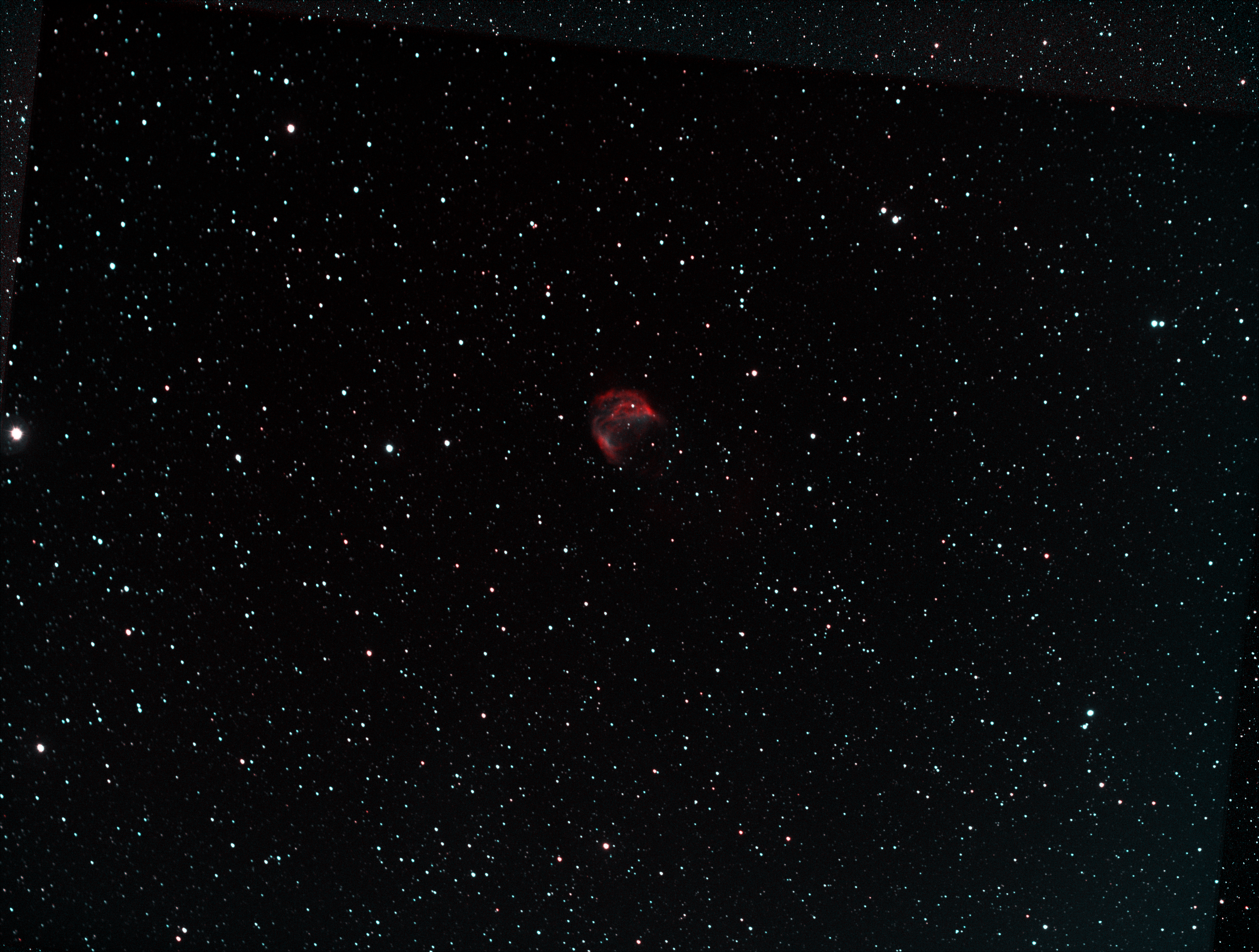

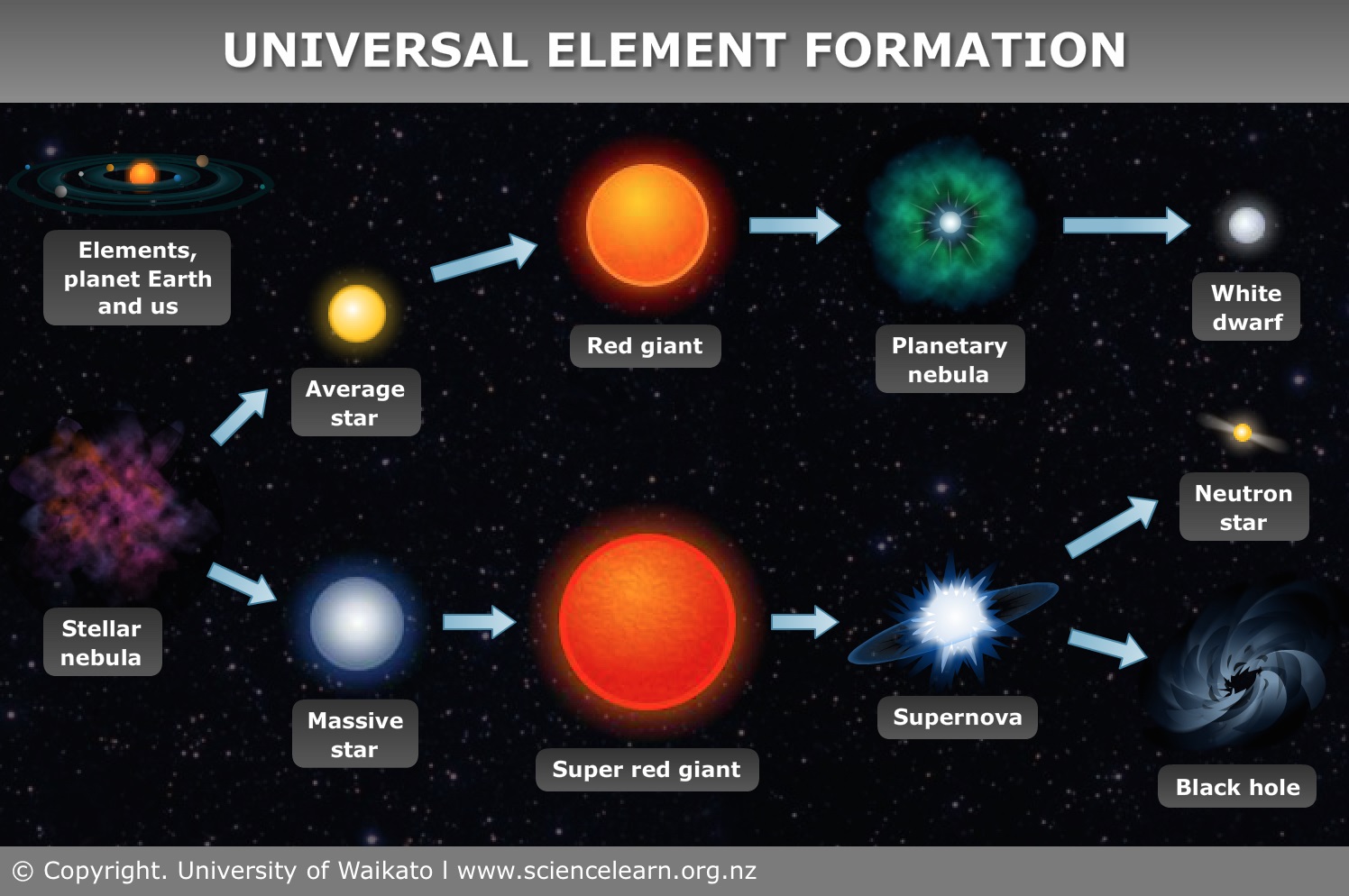

Such objects are usually short lived and unfortunately small and faint, making them a challenge for smaller telescopes and Bortle 5-6 skies, such as I have at Fairvale Observatory. However, I recently decided to return to the Medusa Nebula, a planetary nebula which I previously had imaged as a test in

Such objects are usually short lived and unfortunately small and faint, making them a challenge for smaller telescopes and Bortle 5-6 skies, such as I have at Fairvale Observatory. However, I recently decided to return to the Medusa Nebula, a planetary nebula which I previously had imaged as a test in