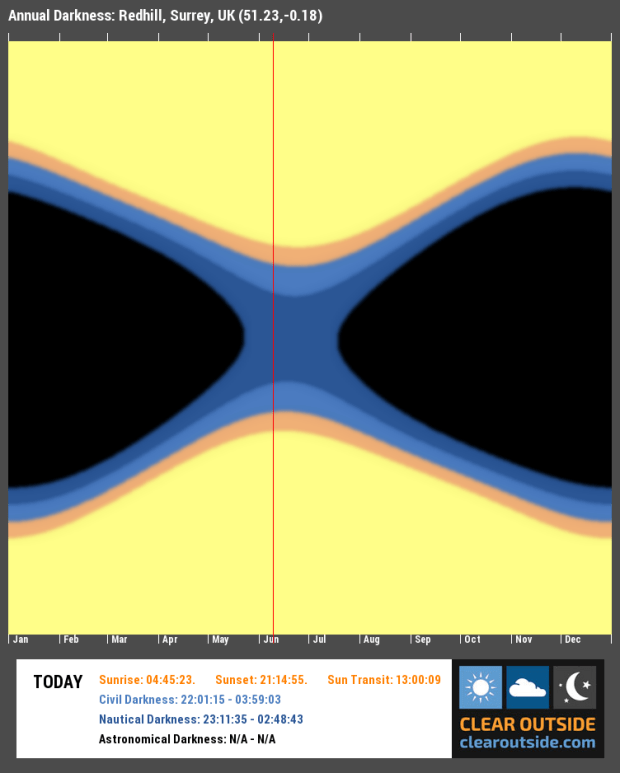

This year the Summer Solstice falls on 20th June at 23.34 BST, meaning the Sun will have reached its furthest point north; as a result from 22nd of May to 19th July 2014 there is a state of permanent Astronomical Twilight AKA Nautical Darkness at Fairvale Observatory. This means there is a complete lack of Astronomical Darkness for imaging, which when combined with short nights poses various problems for astronomy in general. Notwithstanding, there are benefits and other opportunities which are worth exploiting.

Annual darkness at Fairvale Observatory 2016

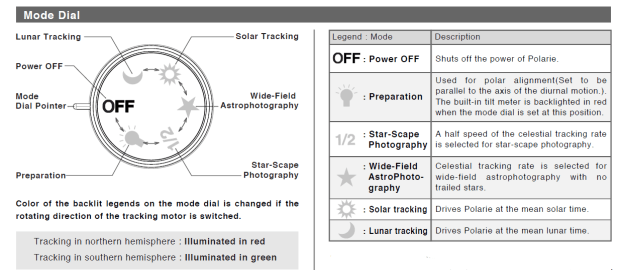

To turn the problem around an obvious solution at this time is viewing and imaging the Sun. However, following the initial success of testing my equipment in preparation for Mercury’s transit of the Sun on 9th May, the actual event proved disastrous for solar imaging. I have subsequently re-checked the equipment and software set-up and the problem has continued but without any obvious reason. Popular opinion on the EQMOD Forum is that it is a software issue – drivers, EQMOD, EOS Utilities – so when time allows over the summer I will reinstall and test everything, hopefully ready for the return of astronomical darkness on 20th July. Murphy’s Law will likely mean it’s something else but for the moment this seems to be the only way forwards, or is it backwards? Having just managed to get guiding to work, I had been looking forwards to a new imaging era but that’s astrophotography!

Although the nights are now short the temperatures have been pleasantly warm; after the long dark but cold nights of winter (and spring this year) it’s been a real pleasure to be outside in summer clothing and without the threat of condensation on the equipment. Notwithstanding, ever present cloud and inevitably the Moon has continued to thwart my efforts until recently, as I have at last just managed a couple of very enjoyable evenings.

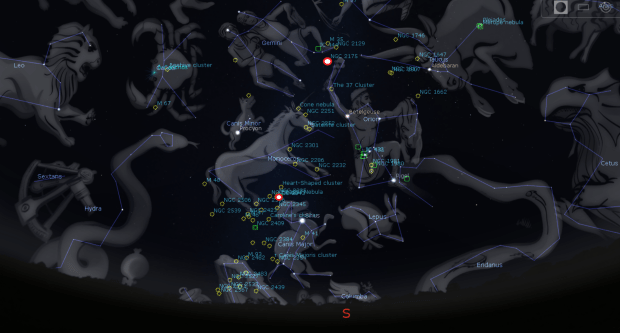

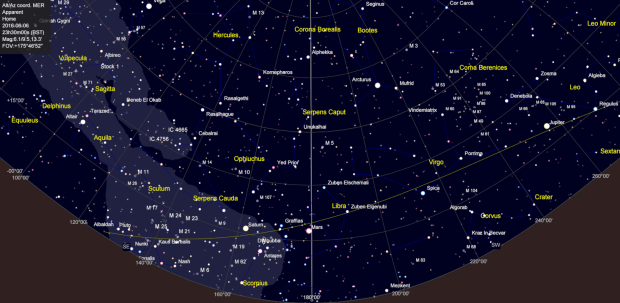

At the moment the three major planets of Jupiter, Mars and Saturn can all be seen at various times between 10.00 pm to nearly 3.00 am, when the early morning light then becomes evident. After putting on a great show during May, Jupiter still remains high in the sky just after sunset. Mars and Saturn are at a much lower declination of between 10o and 17o but provide very good views in the right seeing conditions, especially Mars which with an apparent dimension of 18.6o has recently looked excellent, even to the naked eye.

With such opportunities I decided to try out the Skywatcher 150PL and the ZWO ASI120MC once again. It is almost two years since I used this telescope, preferring instead the superior William Optics GT81 for viewing and imaging. However, with a focal length of 1,200mm and 150mm aperture (f8) the Newtonian scope is better suited to planetary objects; this was also the first time I rigged the scope for use on the AZ-EQ6 GT mount, thus providing better control than the EQ3-2 I have previously used.

Sure enough the views of each planet were very good but also being unaccustomed to the ZWO webcam through lack of use, I failed to obtain any images! Pity but the lesson learned is that I cannot just dabble with this equipment and need to dedicate more time in the future if I am to learn how to use properly again. Nonetheless, it was fun re-acquainting myself with these planets. As an unexpected bonus the ISS also flew right over Fairvale Observatory for over 7 minutes. This time the station was noticeably brighter than previously observed, which I put down to Nautical Darkness and the relative position of the Sun that results, thus producing greater reflection and therefore better illumination of the ISS when viewed from the ground?

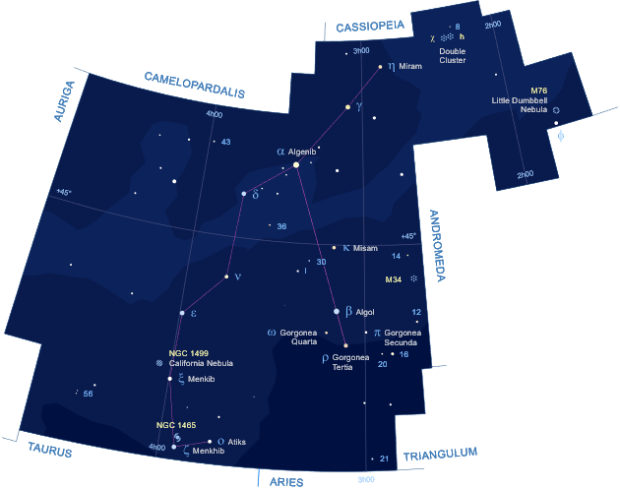

All-in-all after months of difficulties and inactivity it was a good night and at midnight I therefore decided to swap to the William Optics GT81 for some DSO imaging. After setting-up the scope I looked up and, as if from nowhere, broken cloud had rolled in obscuring much of the sky and putting an end to any DSO imaging. Oh well, I had had a good time before and was at least able to get to bed at a civilised time – one of the other drawbacks of summer astronomy. As luck would have it the weather was also good on the following night, probably even better than before and this time I concentrated on bagging some DSO images as the planets again marched across the sky from east to west.

As a result of the aforementioned equipment and software problems I have resorted to the trusty SynScan handset again for alignment and mount control. Impressive though EQMOD and all the other paraphernalia are, so far I have found it all to be somewhat fickle and from my personal experience often unreliable. However, after last year’s enforced astronomy hiatus following my operation and the almost farcical lack of observing conditions over winter and now spring, I’ve become a little rusty with the set-up and as a result, on this occasion encountered my old nemesis – polar alignment – to be something of a problem once again.

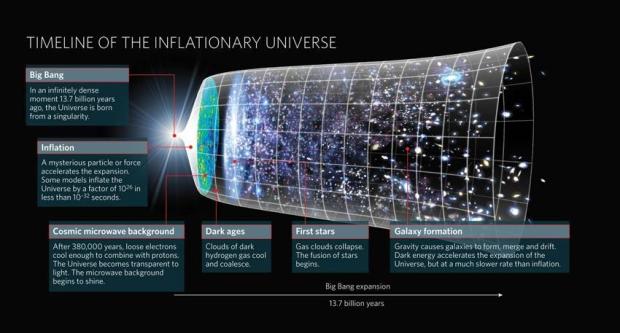

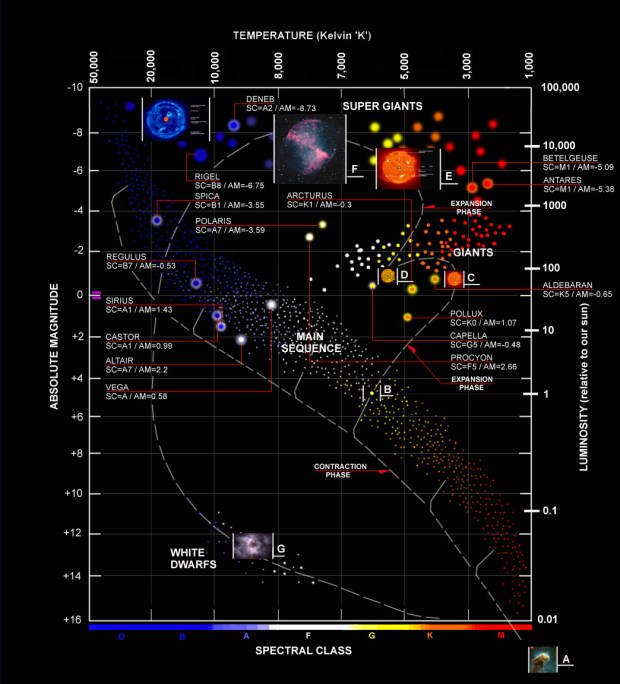

Amongst the types of DSO objects, I find globular star clusters to be particularly intriguing; I had not even heard of such features until taking up astronomy in 2013. Some 158 of these ancient star clusters are known to orbit around the main disc of the Milky Way. At about 11bn to 13bn years old they are very old and despite what so-called experts might say, it seems to me their origin remains something of a mystery; it’s interesting that such clusters are also associated with other galaxies.

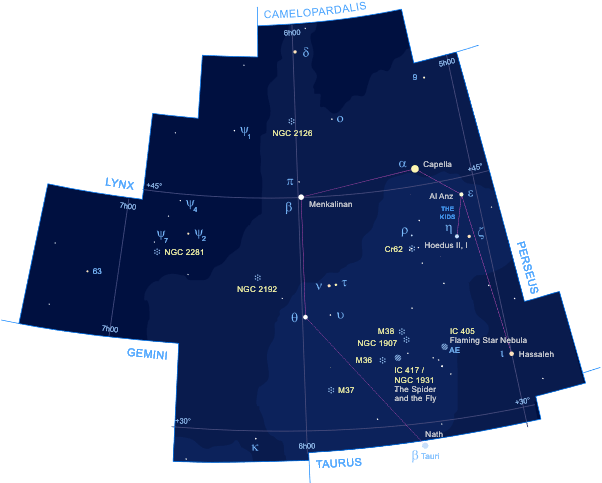

At this time of the year a number of globular and open clusters feature across the night sky and form excellent imaging targets. First up at about 11.00pm was M5 and immediately I discovered the shortcomings of my polar alignment, further aggravated by the decision to try 4.00 minute exposures = big mistake; ironically prior test shots turned about better!

M5 globular cluster + excess trailing! WO GT81 Canon 700D + FF | 9 x 240 secs @ ISO 800 + darks | 6th June 2016

M5 test shot: 10 sec @ ISO 6,400

M5 test shot: 15 sec @ ISO 6,400

Following on from M5 shortly after midnight, M13 appears at a much higher altitude, thus helping to reduce the impact of star trails. Furthermore, as I was by now fully aware of the polar alignment error, I reduced the exposure time from 4.00 to 2.00 minutes; it helped but nonetheless could not hide the impact on the resulting images. Note to self: always ensure good polar alignment. An EQMOD – ASCOM – CdC alignment model would be much better but until I can correct the aforesaid problem it’s down to SynScan and hopefully in the interim I can return to globular clusters once more during summer.

M13 with less but still noticeable trails! | WO GT81 & Canon 700D + FF | 19 x 120 secs @ ISO 800 + darks | 7th June 2016

Before going to bed I couldn’t resist a few quick shots of an old summer favourite, M57 or the Ring Nebula, itself also very high above Fairvale Observatory by this time of night. Considering the alignment problems the image wasn’t too bad, however, the first half of 2016 has really been a case of one step forwards, two back. I hope the next 6-months will be more positive, they will inevitably be darker and colder.

M57 Ring Nebula (left of centre) + Sulafat (left) & Sheliak (right) | WO GT81 & Canon 700D + FF | 13 x 120 secs @ ISO 800 | 7th June 2016

M57 – Ring Nebula, cropped.