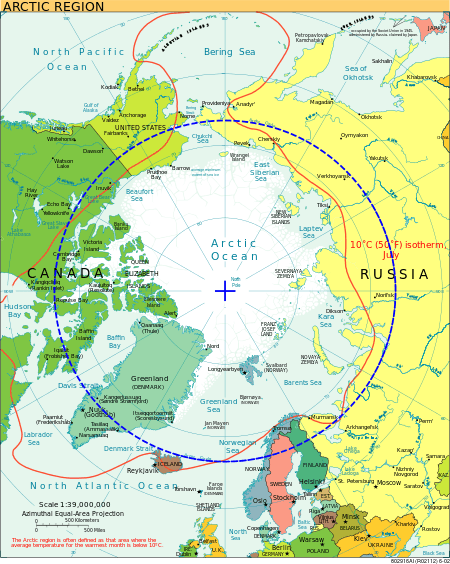

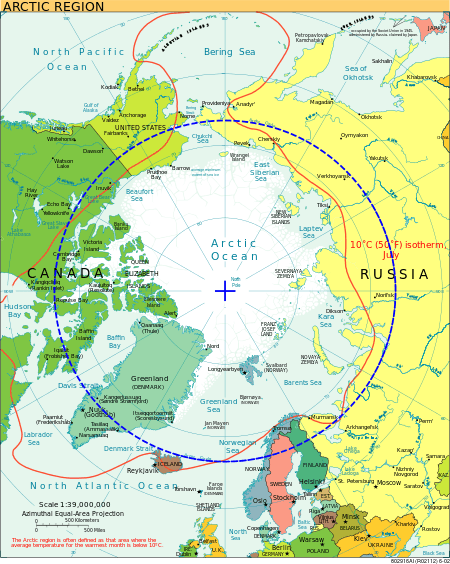

The globe pictured above on the island of Vikingen marks the location of the Arctic Circle off the western Norwegian coast. However, surprisingly the position of the Arctic Circle is not fixed – as of 28 February 2017 it was 66°33′46.6″ north of the Equator but changes depending on the Earth’s axial tilt, which itself varies within 2° over a 40,000-year period due to differing tidal forces that occur as the Moon’s orbit changes around Earth. The region north of the Arctic Circle is famous for the midnight sun in the summer and its corresponding 24-hour darkness during the winter months, with major implications for life itself, as well as contrasting scenery and photographic conditions unique to this hostile region.

During the last two weeks of February, when the return of limited daylight has just begun to mark the end of winter, I travelled by ship along the entire western and northern coast of Norway close to the Russian border, spending much of the time within the Arctic Circle. The area is famous for its beautiful scenery, in particular the fjords which typify the coastline and for time immemorial have posed a significant challenge to all seafarers passing this way.

Looking north at Norkapp 1,306 miles to the North Pole.

Me at 71 10’ 21”N. Nordkapp: the most northerly point on the European Continent.

Our ship, the Richard With, was named after the Norwegian captain who in 1893 pioneered this difficult sea passage which we took from Bergen to Kirkenes and back. Today a fleet of 12 ships are operated by the original Norwegian company Hurtigruten on a daily basis providing ferry transport for goods, vehicles and personnel, as well as a base for tourists seeking a view of the Northern Lights – in all the ship stops at over 30 ports in each direction.

The Richard With in Kirkenes

Scenery doesn’t get better!

Mountains south of Harstad

Apart from the scenery, during the winter months the area north of the Arctic Circle is probably best known for the occurrence of the Aurora Borealis or Northern Lights (Norwegian – Nord Lys). A view of this feature is treasured by all who see them but for astrophotographers it will be one of their ‘must do’ images to acquire. The Aurora is caused by a solar wind originating from the Sun that consists of charged particles, which when drawn downwards at the Earth’s poles by the planet’s magnetosphere ‘excites’ atmospheric atoms which produce different coloured lights depending on the type of gas which is excited by the charged particles; a similar feature occurs around the South Pole called the Aurora Australis and is also now known to occur on Saturn and Jupiter. The lights are mostly green in colour (ʎ 557.7 nm), sometimes red (ʎ 630 nm) or blue (428 ʎ nm) and less commonly pink, ultraviolet or yellow, depending on the altitude and type of excited gas – which is mostly either oxygen or nitrogen. The resulting aurora takes the form of rapidly moving clouds or often curtains of light that dart across the night sky, constantly changing shape under the influence of the Earth’s magnetic field and does not disappoint when seen.

The Northern Lights are best imaged with a standard DSLR camera on a sturdy tripod, using a wide angle lens at full aperture, set at between ISO 800 to 1,600 and exposures of about 8 secs to 25 secs, depending on the brightness and quality of the light and the speed of movement of the aurora; focus and all other control needs to be operated manually for best results. On land a tracking mount, such as a Vixen Polarie, could be used to improve sharpness but on a moving ship set-up and technique is a more difficult.

In this case exposure needs to be carefully balanced in order to account for the ships movement – forwards + up-and-down on the water – and the quality of the aurora light. As exposures will always need to be greater than a few seconds, star trails are unavoidable and have to be dealt with in post processing as best as possible. I found imaging directly forwards or to the rear of the ship helped minimise this effect but still trails were still inevitable. Experimenting with various settings I found about 12 to 15 seconds exposure and ISO 1,600 generally worked quite well but varied depending on the sea conditions and nature of the aurora at any time.

Seagulls following the ship? No star trails, now you see them….

Now you don’t!

At such high latitudes it is still very cold in February and warm head-to-feet-to-hands clothing is absolutely essential. On this occasion, together with wind chill the temperature at the ships bow ranged from between -20oC to -30oC (that’s a minus sign!), making camera control very difficult and uncomfortable! I tried using an intervalometer for remote shooting but as settings have to be changed frequently by hand it was not very practical; I’m sure on land it would prove much more helpful. Furthermore, much of the time I had to hold the tripod down with some force as the wind was very severe.

Before the show starts – sunset at Trollfjord

Venus looks down on the Raftsundet passage through the eastern Lofoten Islands

Notwithstanding, I’m very pleased with the results shown below and would love to return again one day, perhaps in the summer – it is a truly different and very special part of the world – hat’s off to Richard With and all those who still sail these waters.