At this time of the year, I produce an astrophotography calendar for members of my family, which consists of my better images from the year just ended. In combination with the calendar, I also compile a video of the calendar images set to appropriate music, which we all watch together prior to seeing the actual calendar. It’s a great way to present the images, which look really stunning on today’s large Smart TV’s and is also fun to watch with the family.

2022 CALENDAR

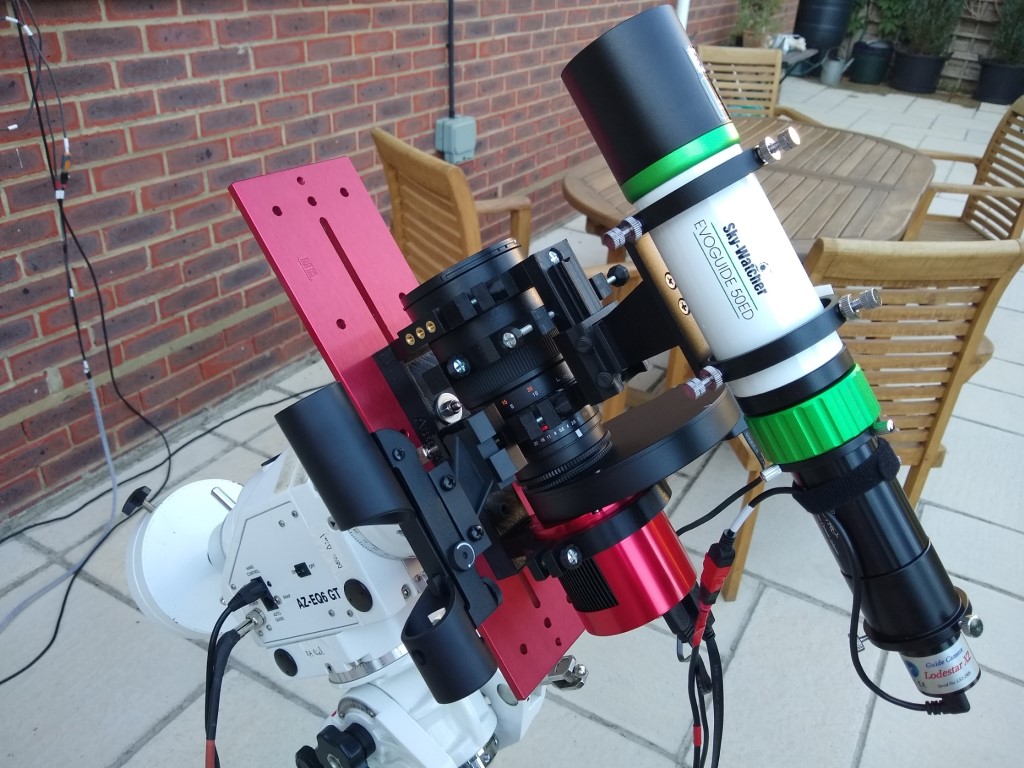

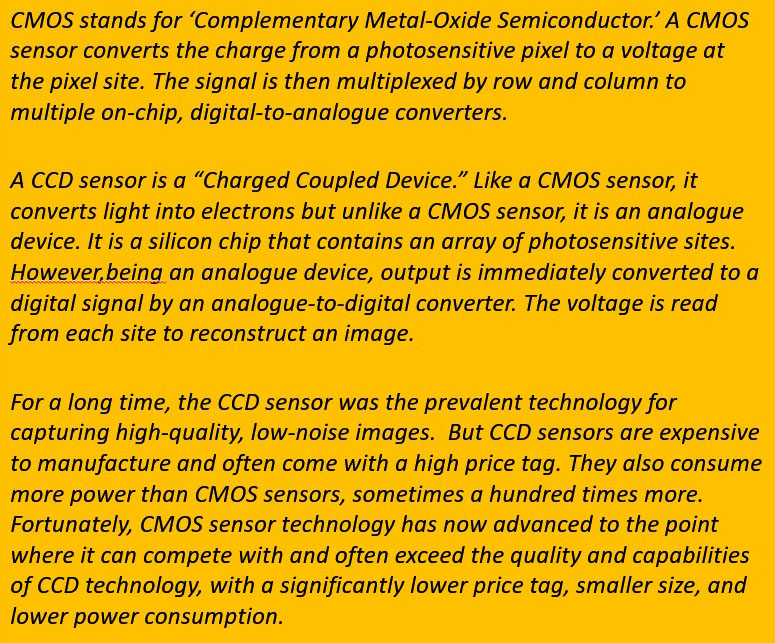

Last year’s new Chroma filters, a new ZWO ASI294MM camera, further processing improvements, dark sky data from a remote Takahashi 106 telescope in New Mexico, USA (indicated by an asterisk *) and the addition of a new widefield rig built around the excellent Samyang 135 lens, contributed to a successful astrophotography year in 2022.

The said calendar video can be viewed on YouTube by clicking HERE and below is a brief overview of each image. More detailed background information and imaging details for those interested can be found in relevant blogs I posted on this website during the year. The background music is the track Leaps and Bounds from Nils Petter Molvaer’s album Re-Vision.

| COVER | Pickering’s Triangle: A close-up, starless section of the Cygnus Loop SNR (Supernova Remnant). |

| JANUARY | M45 Pleiades Nebula: An open star cluster containing over 1,000 stars formed in the last 100 million years. Hot, blue stars are passing through an interstellar dust cloud, with the blue light from the brighter stars reflected off the interstellar dust. |

| FEBRUARY | Cone Nebula: Located 2,500 light-years from Earth, this rich star forming region is full of hydrogen gas, reflection, and dark nebulae. With nearly 14-hours exposure time this narrowband image shows the Christmas Tree open star cluster, Cone Nebula, and the Fox Fur Nebula to good effect. |

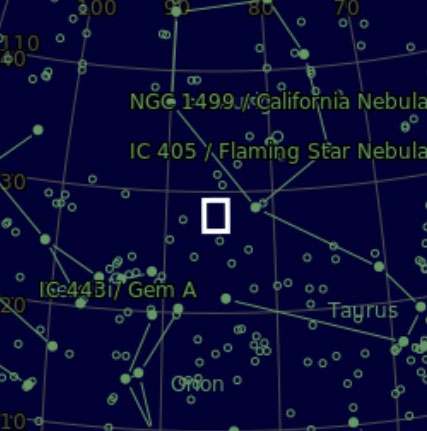

| MARCH | Barnard-22: Close to the aforesaid Pleiades, lies the dark region of the Taurus Molecular Cloud (TMC), which at 430 light-years is the nearest star-forming region to Earth. Consisting of hundreds of solar masses of primordial hydrogen and helium gas, as well as heavier elements, this vast area of dense stardust obscures almost all light from behind; Barnard-22 forms part of the TMC. |

| APRIL | Helix Nebula*: This iconic planetary nebula in the Aquarius constellation was formed by a star near the end of its life shedding its outer layers, which is expelling the resulting gases into space. |

| MAY | Thor’s Helmet*: An emission nebula, produced as a hot dying star, 20-times more massive than the Sun, emits a stream of particles expanding outwards, thus producing an interstellar bubble which here interacts with nearby molecular clouds and gives the nebula its form and glow. |

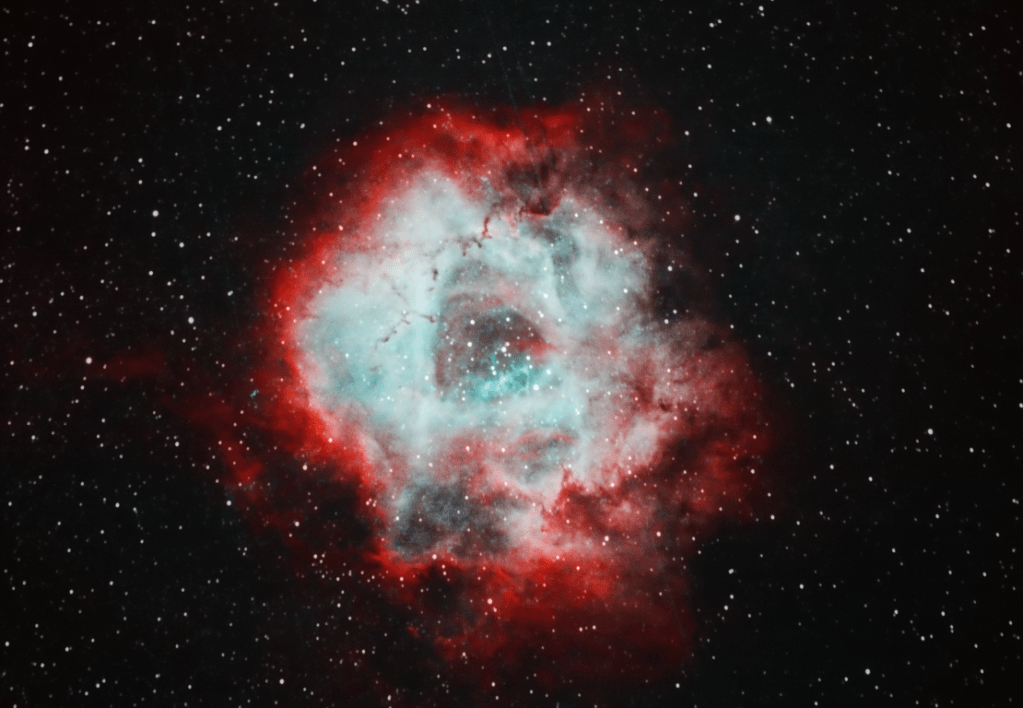

| JUNE | Lower’s Nebula: Located in the outer regions of the Orion constellation, between the Orion and Perseus arms of the Milky Way, the nebula mainly consists of ionized hydrogen, which is thought to be energised by a runaway star situated at its centre. |

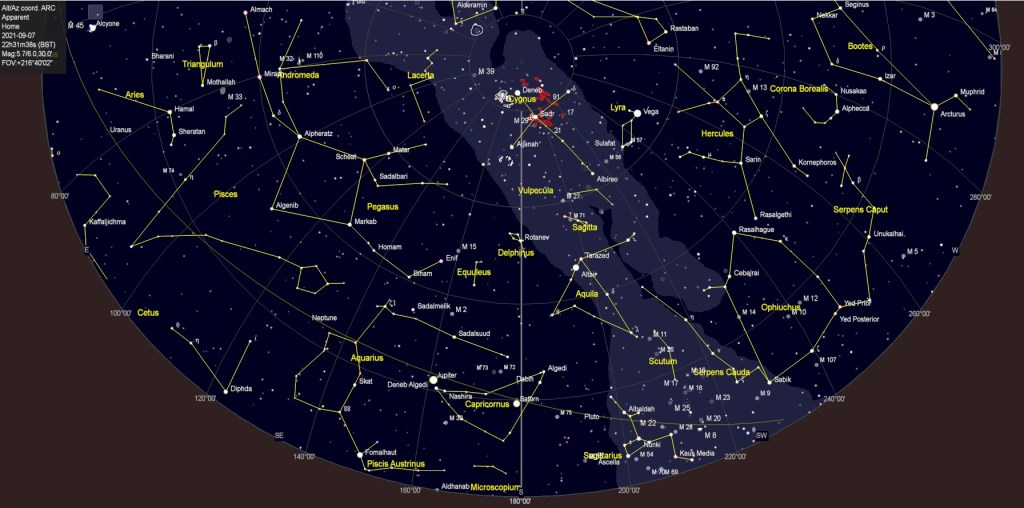

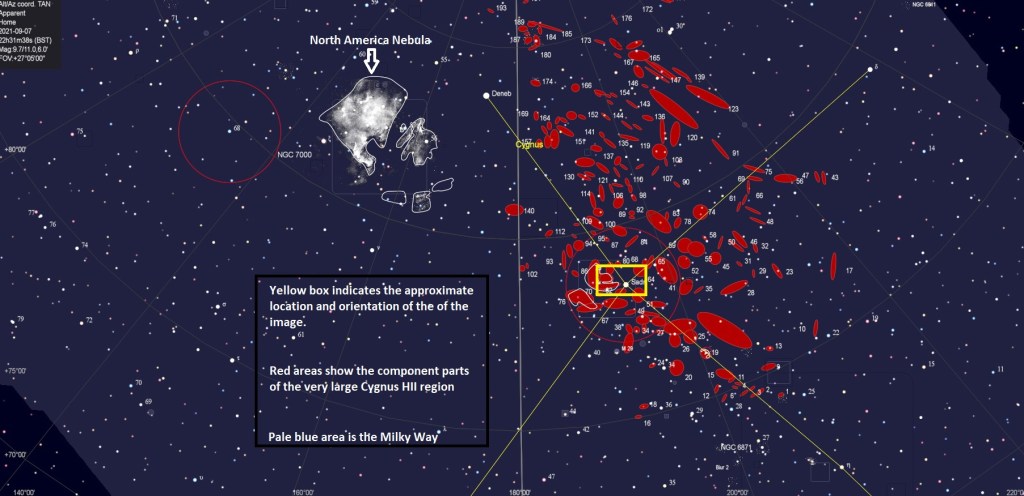

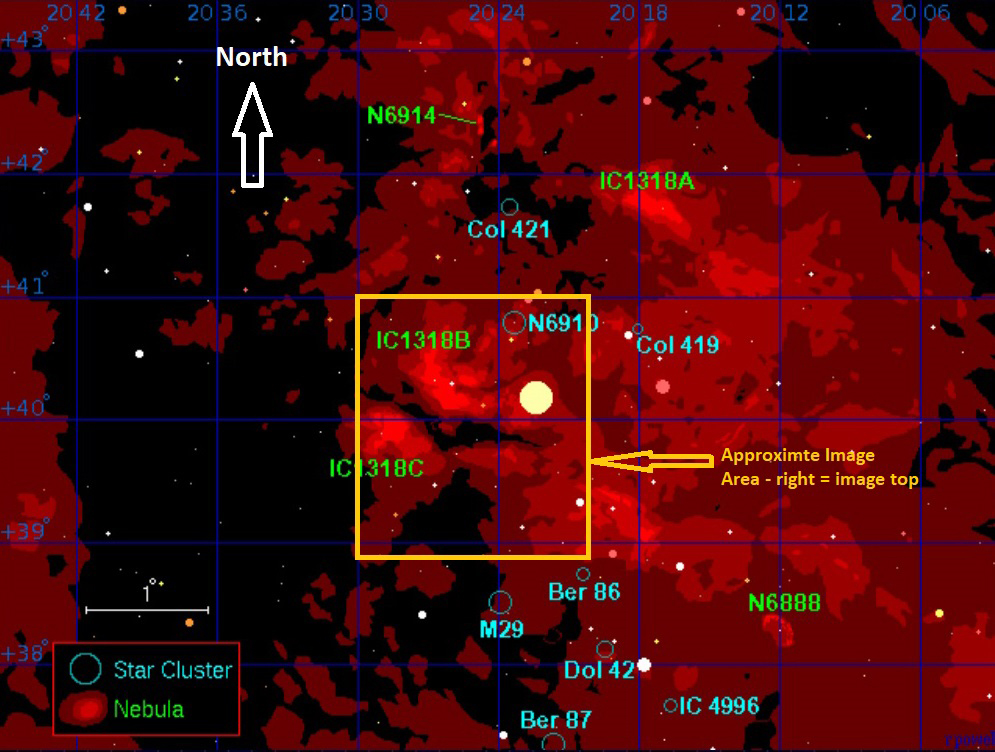

| JULY | Sadr Region: This busy image uses a new widefield lens (8 x greater than my telescope’s field-of-view), framed to include some familiar objects across the very large Cygnus-X region, including the yellow-white supergiant Sadr star, Butterfly Nebula (top right) and the Crescent Nebula (centre). |

| AUGUST | Cygnus Loop / Western Veil Nebula: Located 1,500 light-years from Earth, this supernova is still expanding at 60 miles per second. The debris cloud has been sculpted by shock waves from the star’s explosion, with the colours arising from ionized hydrogen (red) and oxygen (blue) gases. |

| SEPTEMBER | Bodes & Cigar galaxies*: Located in the constellation of Ursas Major, Bodes spiral galaxy and the Cigar irregular galaxy are 11.8 million light-years distant. These galaxies have a gravitational lock on each other which has affected the shape and composition of each other. |

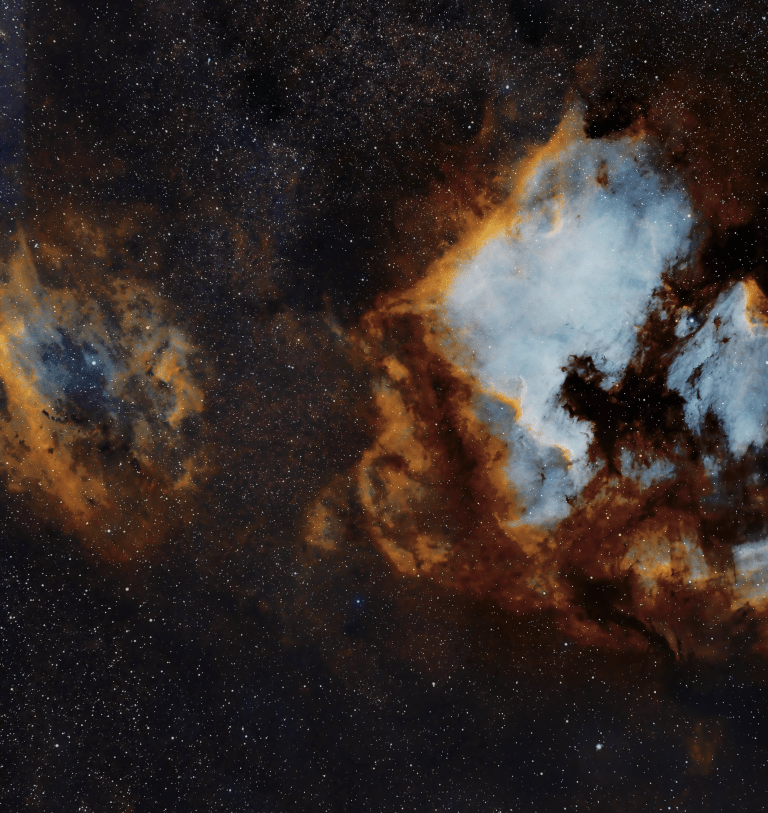

| OCTOBER | Clamshell, North America & Pelican Nebula: The Cygnus constellation is rich in targets and by using the new widefield lens, it was possible to capture all three nebulae in one narrowband image. |

| NOVEMBER | Horsehead & Flame Nebula: An old favourite located in the Orion constellation, here for the first time imagedin LRGB wavelengths to produce this colourful and exciting image. |

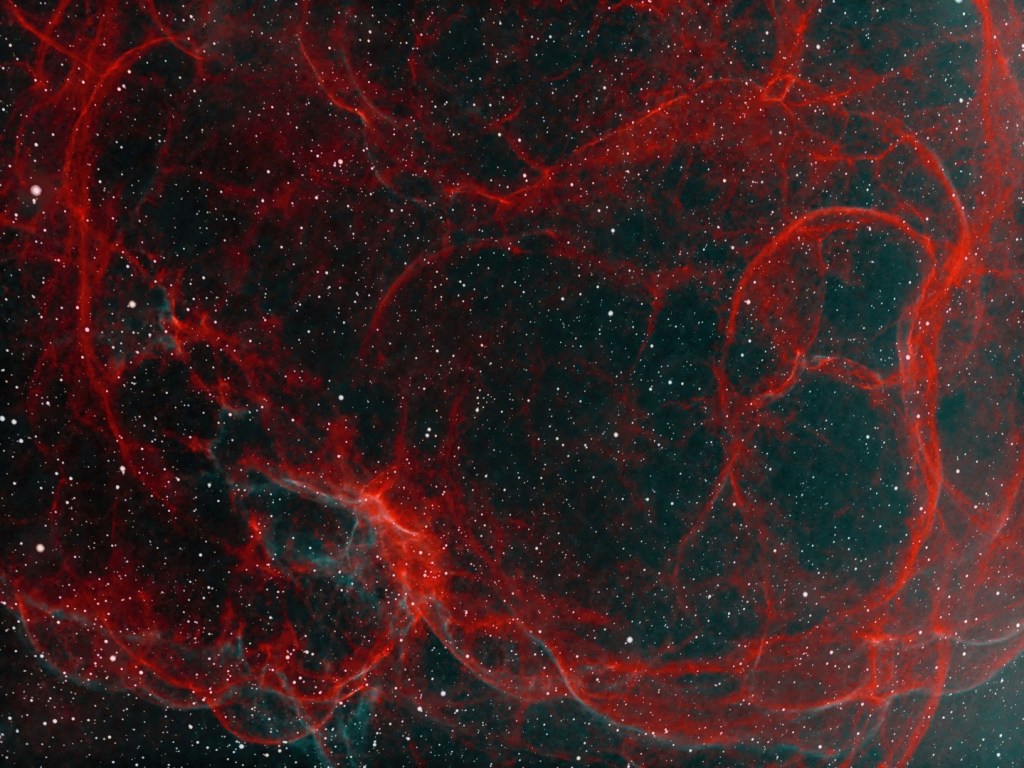

| DECEMBER | Spaghetti Nebula: The beautiful complexity of this cosmic cataclysm is the product of a massive stellar explosion that took place some 40,000 years ago. Aptly named, the image concentrates on the southern lobe of this very large supernova remnant. |

| HAPPY NEW YEAR & CLEAR SKIES IN 2023 |