Aside from all the paraphernalia required for astrophotography, two other critical items are essential to start imaging: clear skies and darkness. This year astronomical darkness ceased on 25th May at Fairvale Observatory and remained absent for the next 8-weeks whilst Earth performed its annual summer gyration about the Sun, culminating on 21st June with the solstice. As a result this period is typically quite a barren time for astronomers, especially for those in the higher latitudes where the sun does not set for the entire 24-hour day. Some options during this time are: give up, stop imaging and use the time to sort out equipment, if you have the right equipment change to solar astronomy or just enjoy what happens to be about in the less than dark sky. This year I chose the latter, during what has been a very hot summer, often with continuously clear skies for days-on-end.

From the early evening we’ve been treated to views of all the planets of the Solar System, as during the short nights one-by-one they transited along the ecliptic, though were relatively low in the sky seen from the UK. In order of appearance, the main show (see above) each night has been that of Jupiter, followed by Saturn and finally at about 2.00 a.m. (June) Mars – which this year was an unusually large, unusually bright red disc as it reached its closest orbit relative to Earth for almost 60,000 years – all of which could be clearly seen with the naked eye. Unable to sleep in the hot weather, night after night I was able to view and sometimes imaged the aforesaid planets with a DSLR camera as they moved across the night sky.

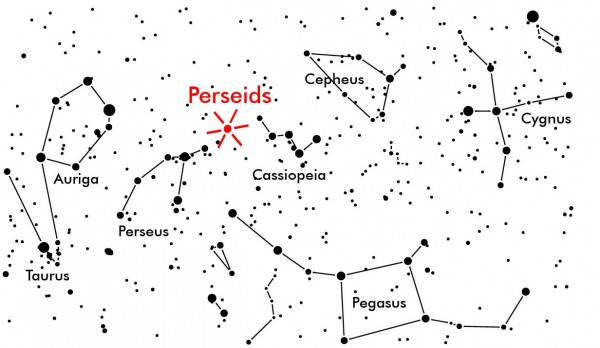

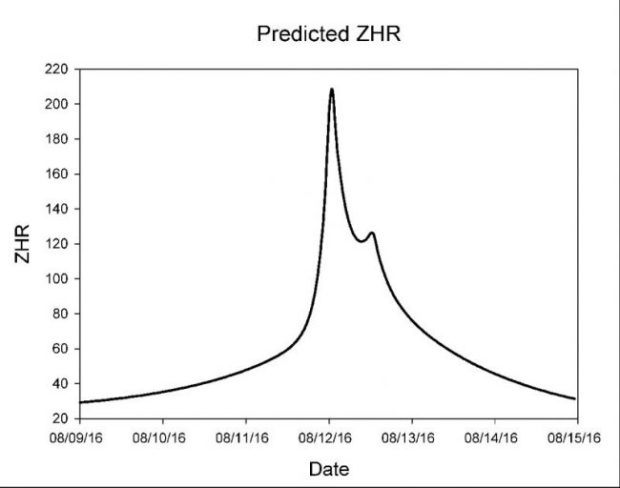

Shortly after darkness started to return on 20th July came two further special events. First on 27th July a lunar eclipse, that despite all the previous clear nights was ironically obscured by cloud cover over most of the UK! Fortunately, clear skies returned for 13th August and the annual Perseids meteor shower, which on this occasion produced some of the best meteor trails I have personally experienced.

And so, with astronomical darkness back and the chance to return to the recently established Fairvale Observatory South AKA The Shed Observatory, it was time to resume my hitherto brief imaging experience of the northern sky again. As a newcomer to this part of the night sky there were considerable new imaging possibilities to explore but only one I now wanted to capture – the Heart Nebula or IC 1805 (also known as the Running Dog Nebula when viewed from a different angle).

The Heart and nearby Soul Nebula are situated in a busy region of the sky (see above – from Wikisky), which also contains seven open clusters of young stars, as well as the Pacman Nebula and galaxies of Maffei 1 & 2 and M31 Andromeda. The discovery of a bright fish-shaped HII object – known as the Fishhead Nebula IC 1795 or NGC 896 at the edge of the main object – preceded that of the Heart Nebula itself in 1787 by William Herschel. The Heart Nebula has a red glow, a result of intense radiation emanating from a small cluster of large, hot, young (1.5 My) bright-blue stars at the centre known as Melotte-15. The stellar wind and stream of charged particles that flow out from these newborn stars then creates the characteristic heart-shape of the nebula from the stellar dust and hydrogen gas clouds.

The Heart and nearby Soul Nebula are situated in a busy region of the sky (see above – from Wikisky), which also contains seven open clusters of young stars, as well as the Pacman Nebula and galaxies of Maffei 1 & 2 and M31 Andromeda. The discovery of a bright fish-shaped HII object – known as the Fishhead Nebula IC 1795 or NGC 896 at the edge of the main object – preceded that of the Heart Nebula itself in 1787 by William Herschel. The Heart Nebula has a red glow, a result of intense radiation emanating from a small cluster of large, hot, young (1.5 My) bright-blue stars at the centre known as Melotte-15. The stellar wind and stream of charged particles that flow out from these newborn stars then creates the characteristic heart-shape of the nebula from the stellar dust and hydrogen gas clouds.

Located in the Perseus arm of the Milky Way in the Cassiopeia constellation, this large emission nebula is an excellent object for narrowband imaging at all wavelengths and is also well framed in the field-of-view of my telescope-camera combination; the images presented here are rotated 180 degrees to achieve the correct orientation to see the heart shape, with the Fishhead Nebula located in the bottom right corner. Not surprisingly this large HII object produces strong Ha subs, which make a pleasing stand-alone image (above section). But the OIII and especially SII wavelengths are also very good, resulting in very good HHOO bi-colour (top-of-the-page) and SHO (below) images too.

The limited time I’ve had to image the northern sky for the first time this year has already proved to be exciting and bodes well for the future. On this occasion I’ve been very pleased with my first imaging results of the Heart Nebula, which is a superb object for my equipment and am sure to return next year given suitably clear skies and, of course, darkness.

| IMAGING DETAILS | |

| Object | Heart Nebula IC 1805 AKA Running Dog Nebula Sharpless 2-190 |

| Constellation | Cassiopeia |

| Distance | 7,500 light-years |

| Size | 150’ x 150’ = 2.5o or 200 light-years |

| Apparent Magnitude | +18.3 |

| Scope | William Optics GT81 + Focal Reducer FL 382mm f4.72 |

| Mount | SW AZ-EQ6 GT + EQASCOM computer control |

| Guiding | William Optics 50mm guide scope |

| + Starlight Xpress Lodestar X2 guide camera & PHD2 control | |

| Camera | ZWO1600MM-Cool (mono) CMOS sensor |

| FOV 2.65o x 2.0o Resolution 2.05”/pix Max. image size 4,656 x 3,520 pix | |

| EFW | ZWOx8 + ZWO LRGB & Ha OIII SII 7nm filters |

| Capture & Processing | Astro Photography Tool + PS2, Deep Sky Stacker & Photoshop CS2, HLVG |

| Image Location & Orientation | Centre RA 02:33:09 DEC 61:24:23

Top = South Right = West Bottom = North Left = East |

| Exposures | 20 x 300 sec Ha + 10×300 sec OIII & SII (Total time: 200 minutes) |

| @ 139 Gain 21 Offset @ -20oC | |

| Calibration | 5 x 300 sec Darks 20 x 1/4000 sec Bias 10 x Flats Ha-OIII-SII @ ADU 25,000 |

| Location & Darkness | Fairvale Observatory – Redhill – Surrey – UK Typically Bortle 5 |

| Date & Time | 16th & 17th August 2018 @ +23.30h |

| Weather | Approx. 12oC RH <=95% |