As Douglas Adams succinctly puts it in the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxies: Space…..is big. Really Big. If he had lived longer, even he would be surprised to learn how true these words were. Recent analyses using data from the James Webb Space & Hubble Telescopes, suggests there could be some 2 trillion galaxies. Notwithstanding, as this applies only to the observable universe, which is about 93 billion light-years across, the entire universe could be significantly larger, with many more galaxies beyond what we can already observe!

Perhaps then it is not so surprising that from time-to-time galaxies run into each other – our own Milky Way Galaxy is expected to collide with the Andromeda Galaxy in about 4.5 billion years. But there are already many exciting examples of such phenomena that we can image today, of which the Antennae Galaxies are one of the most famous and visually striking examples of two colliding galaxies. Located in the constellation Corvus, they provide a striking insight into what happens when massive galaxies merge – a process that reshapes their structure, triggering intense star formation, thereby setting the stage for the eventual creation of a single, larger galaxy, all played out over 100’s or even billions of years.

The Antennae Galaxies earned their name from the long, curved tidal tails of gas, dust, and stars that extend outward from the colliding pair of galaxies (NGC 4038 & 4039), thus resembling the antennae of an insect. These tails were created by the immense gravitational forces at play during the collision. As the two galaxies then pass through each other, their mutual gravity distorts their original spiral shapes, pulling out vast streams of stars and interstellar material. These tidal tails stretch for tens of thousands of light-years, making them some of the most spectacular features of any known galactic merger.

At the core of the Antennae Galaxies lies a chaotic and extremely active region. The violent gravitational interactions have compressed enormous clouds of gas and dust, sparking a burst of intense star formation, at a rate hundreds of times faster than that of our own Milky Way. Many of these newly formed stars are massive but short-lived, destined to explode as supernovae, thus enriching the surrounding space with heavy elements. Within another 400 million years, the Antennae’s nuclei will collide and therafter become a single galactic core with stars, gas, and dust swirling around it.

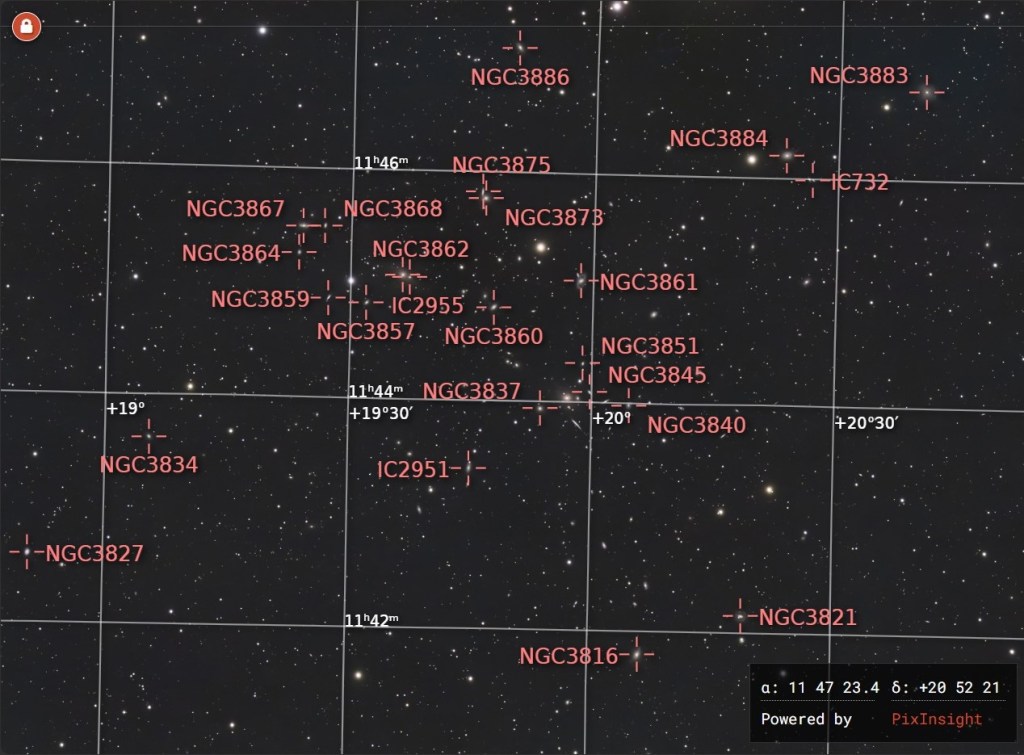

Imaging such a feature from Earth requires significant telescopic power, the darkest of night skies and the acquisition of lots of data. Located at the El Sauce Observatory in Chile, 50 hours of data acquired using the Planewave CDK20 astrograph is such a set-up worthy of the task. However, despite the excellent data quality, I found processing this complex event difficult so as to both show the complexity of the merging galaxies, whilst at the same time preserving the delicate nature of the tails of galactic debris. The final image is as profound as it is beautiful, demonstrating the immense forces across the cosmos and the inevitable consequences for the many galaxies that occupy the vastness of the Universe.

| IMAGING DETAILS | |

| Object | NGC 4038 & 4039, AKA Antennae Galaxies |

| Constellation | Corvus |

| Distance | 62 million light-years |

| Size | 5.21 x 3.1 arc minutes (actual 634,410 x 456,780 light years) |

| Apparent Magnitude | +10.3 / 10.4 |

| Scope | Planewave CDK20 |

| Mount | Planewave L500 |

| Focuser | Optec Gemini |

| Camera | QHY600PH-M |

| Filters | Chroma LRGB + Ha 3nm |

| Processing | Deep Sky Stacker & PixInsight v1.9-3 |

| Image Location & Orientation | Centre: RA 12:01:54.47 DEC -18:52:45.2 Up = North |

| Exposures | Ha 117 x 10 mins, L x 127, R x 80, G x 80, B x 70 @ 5mins Total Integration Time: 50hr 5min |

| Location & Darkness | Obstech El Sauce Observatory, Chile |

| Date | February 2025 |