It’s nearly 4-years since I started astronomy, like so many inspired after observing Saturn through a telescope. Not just any telescope but the 13” Astrographic Refractor at the Observatory Science Centre in Herstmonceaux. Built in 1890 specifically to make use of the then new technique of astrophotography, the telescope was first employed as part of the worldwide Carte Du Ciel project to map the entire night sky by photography and subsequently for a crucial test of Einstein’s then new theory of General Relativity. Soon thereafter I was to view the aforesaid planet once again with my first, newly purchased Skywatcher 150PL Newtonian telescope. Inevitably something of a lesser view than that at Herstmonceaux it was nonetheless just as exciting, if not more so. I was hooked!

I then attempted afocal imaging using a compact camera held up to the telescope eyepiece but with poor results, except in one respect. By clamping the camera onto the front of the eyepiece and achieving longer exposures, nebulosity otherwise unseen with the naked eye was revealed in the resulting image, in this case Orion’s Nebula. As crude as the image was, for me the penny had dropped and I’ve been pursuing images of the hidden beauty of the night sky ever since.

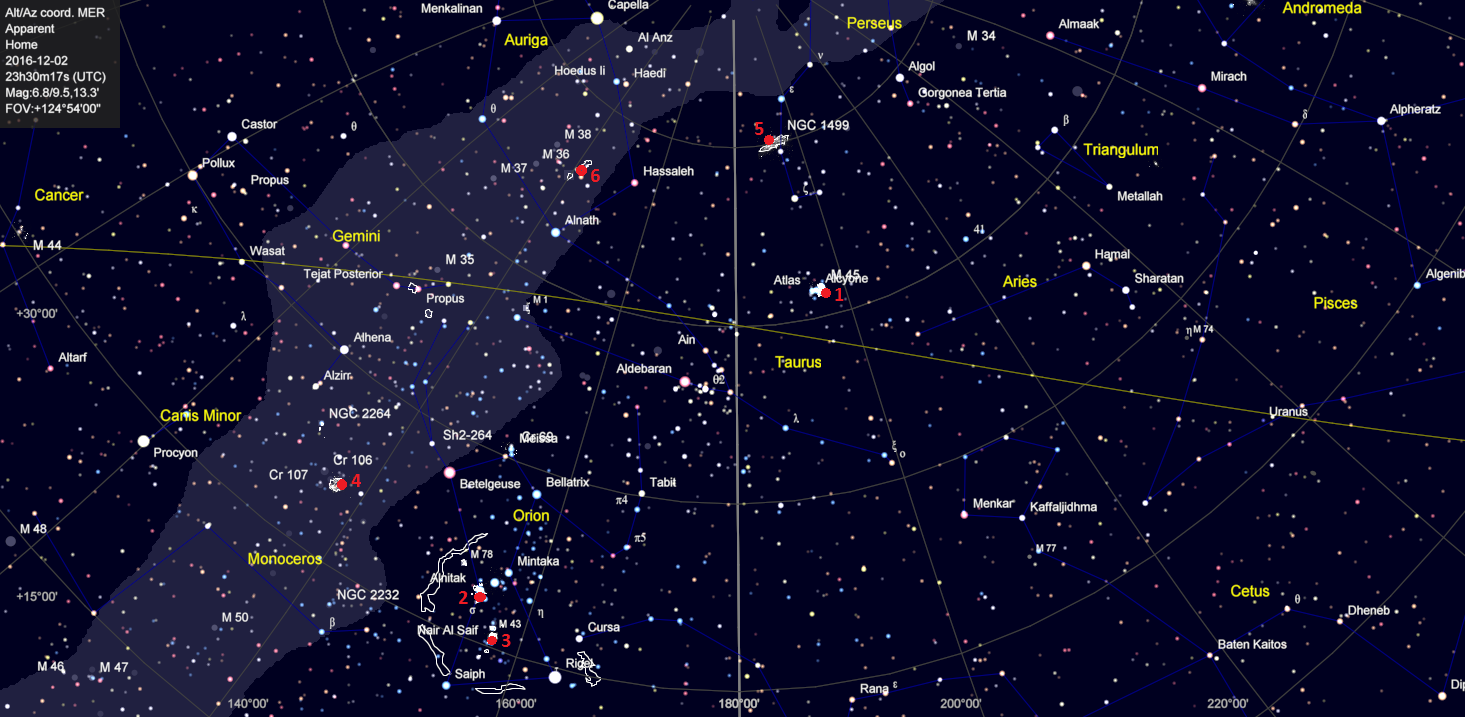

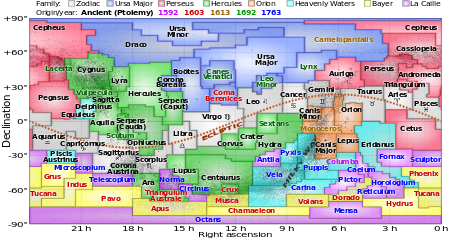

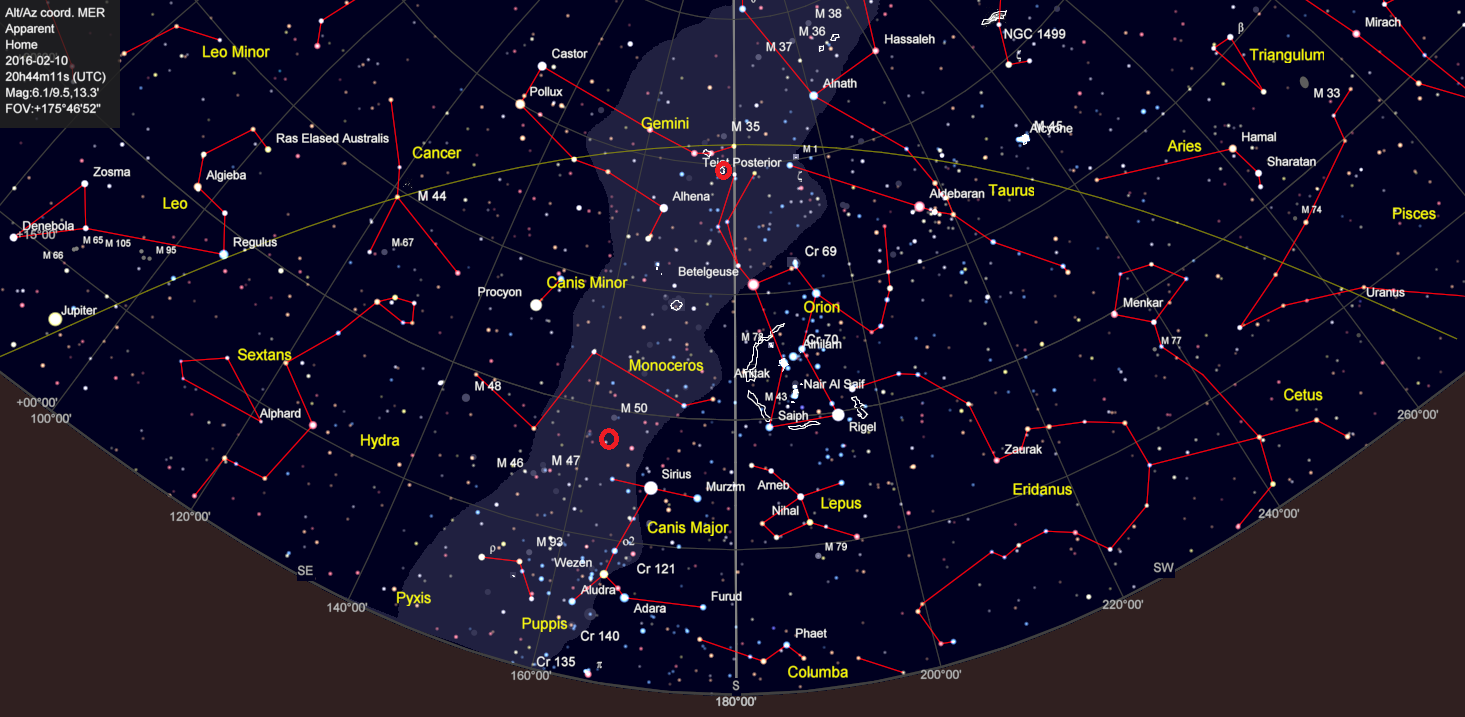

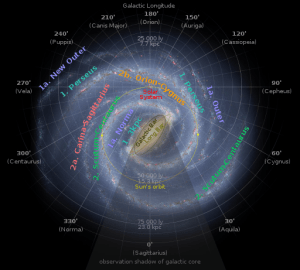

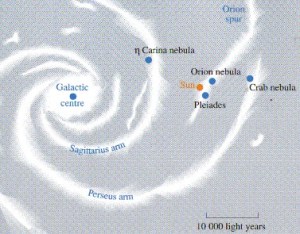

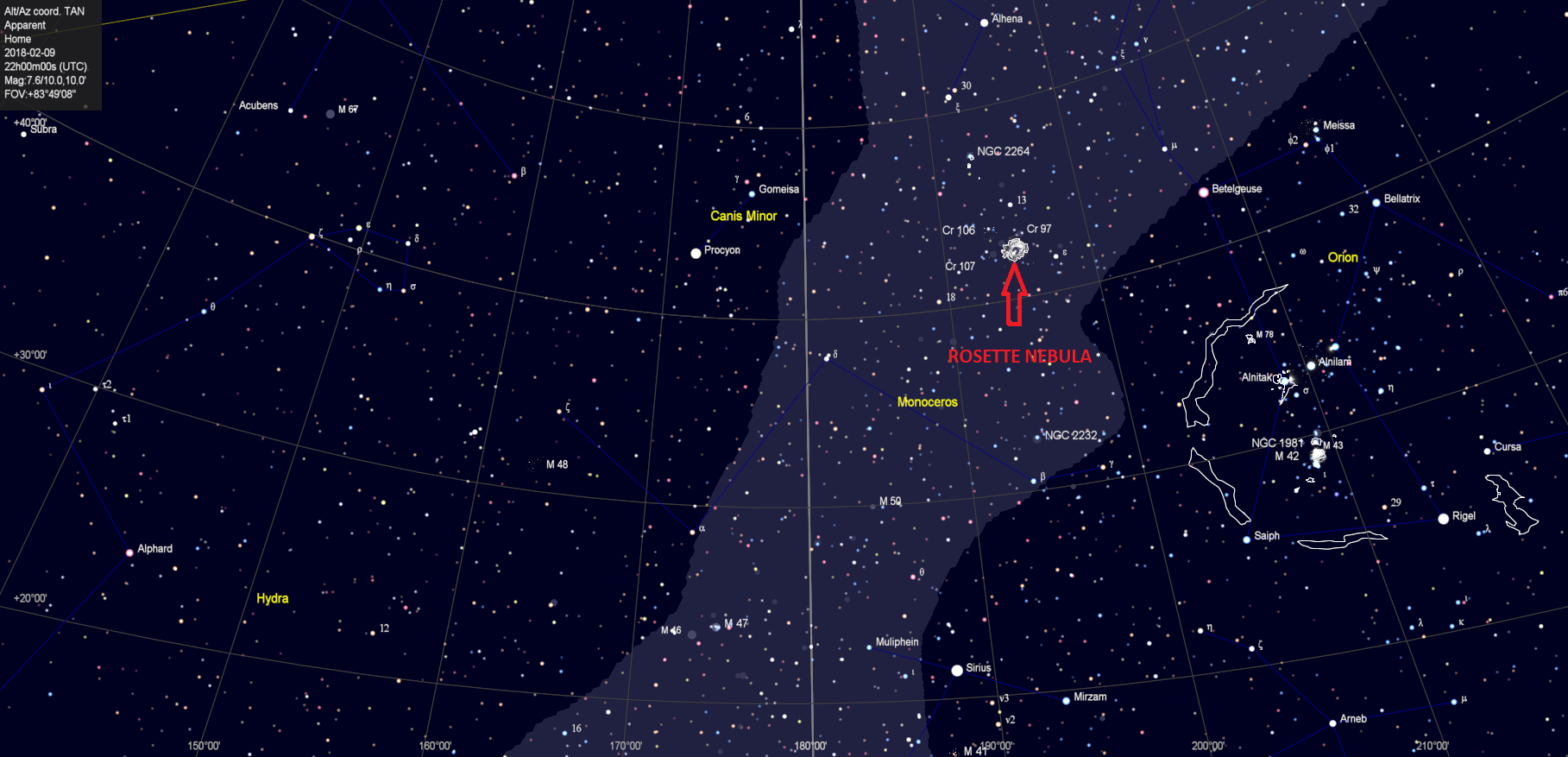

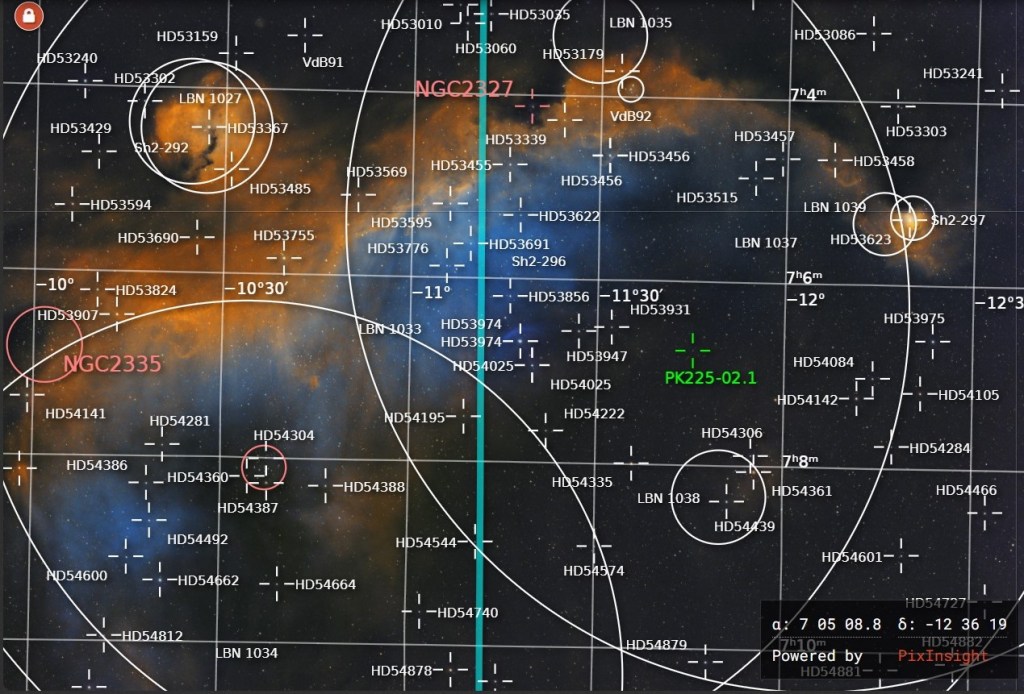

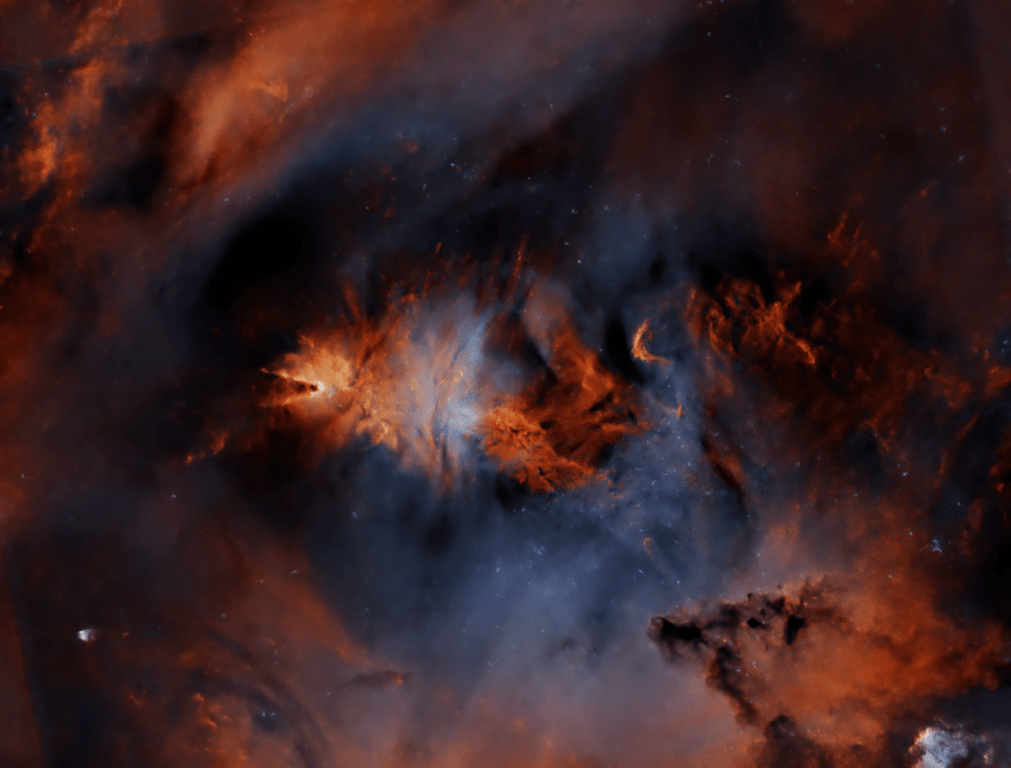

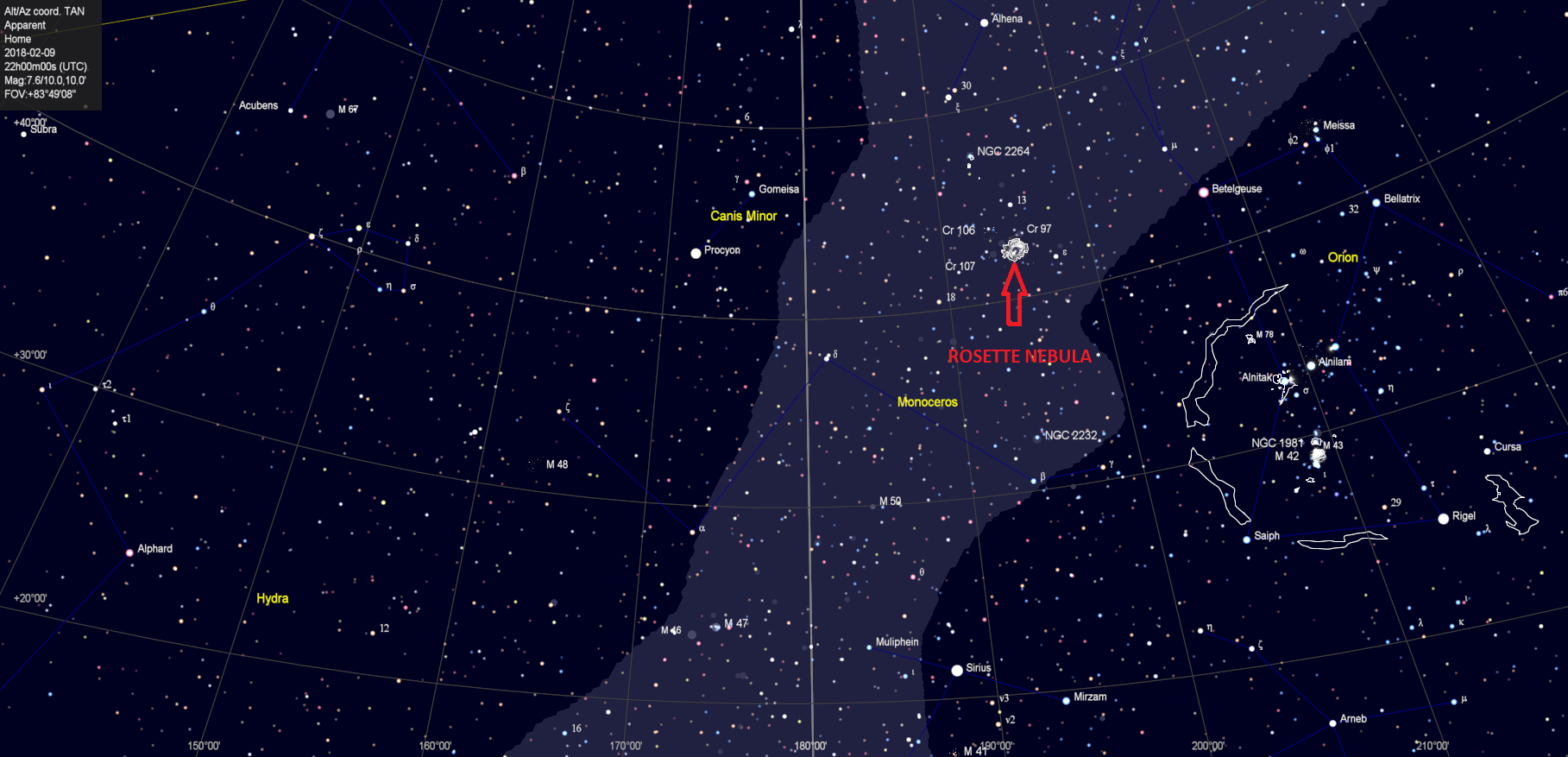

Like mariners, through astronomy I have by now become accustomed to the seasonal procession of the night sky wonders throughout the year, none more so than the Rosette Nebula. About 100 light-years across and 5,000 light-years from Earth, the Rosette Nebula is surely one of the annual highlights for most astrophotographers? Located just east of Orion, the Rosette is at its best between December and February, so that I was first able to image this beautiful object myself at the end of 2014.

As a very large HII region the Rosette Nebula emits light mainly at narrowband wavelengths, which produces wonderful but mainly red colours when imaged with a modded DSLR camera. As my astrophotography and equipment have since developed, it has become a pleasure and challenge to image objects as they return each year such as the Rosette, thereby also charting my own improvements or otherwise from year-to-year. Its size makes the Rosette an especially attractive target for smaller telescopes such my own with an 81mm aperture, which nicely fills much of the sensor of an APS-C camera.

Despite having purchased a new ZWO1600MM-Cool mono camera at the end of 2016, by the time I was ready to use it at the end of the following March, the Rosette Nebula had almost disappeared over the western horizon for another year. Notwithstanding, in the limited time remaining I managed to capture a few Ha-OIII-SII subs, thus marking first light for the camera, which ironically resulted in one of my favourite images for 2017. Using narrowband for the first time it was immediately possible to see the potential of the new camera when imaging this type of object.

Returning from an extended overseas trip at the end of January this year, 10-months had passed since my last encounter with the Rosette Nebula last March and I found myself with the first real opportunity to image the nebula properly with the ZWO1600MM-Cool camera. Since last year I’d acquired more knowledge and experience with the camera, plus this time the Rosette was now in the south eastern quadrant and provided significantly more imaging time than before.

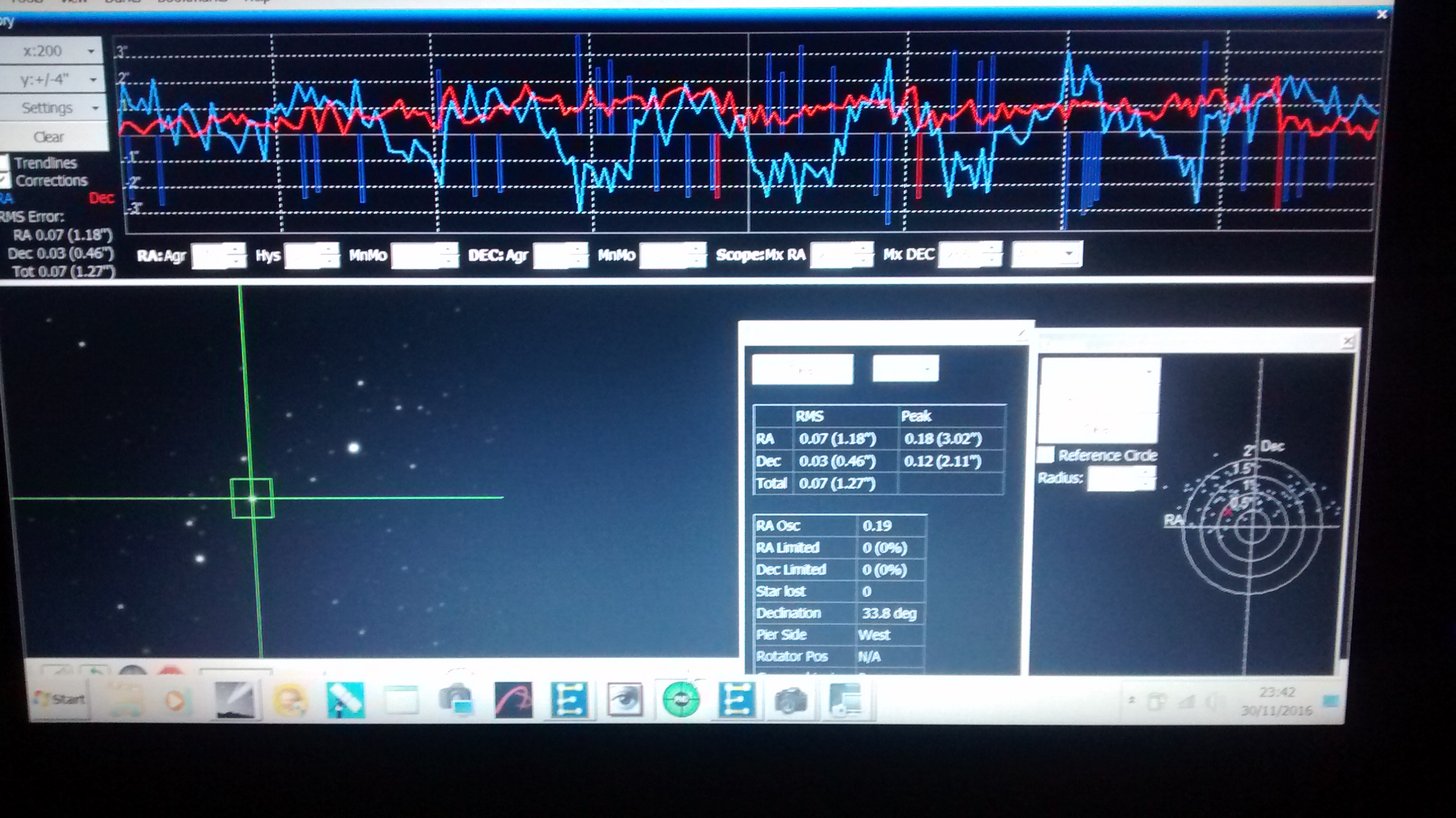

After a break of nearly two months I needed to sort out the equipment, refocus the camera and start a new alignment model in EQASCOM. For the first time I also decided to use longer exposure times of 300 seconds, which altogether produced a good Ha+OIII Bi-Colour image (top of page – awarded BAA Picture of the Week 4th March 2018); whilst much longer exposures are used with conventional CCD sensors, such is the sensitivity of the CMOS mono sensor in the ZWO camera that 5-minute exposures provide exceptionally good quality data. Overall the impact of longer exposure, good focus, tracking and much longer total integration time had a noticeably positive impact on noise and overall image quality, though there’s still room for improvement – there always is!

To some extent, even after a year I’m still in the experimental phase with this camera. For most of 2017 I used a high gain setting of 300 but this time I chose the Unity gain setting of 139 and for interest also imaged at a shorter exposure of 180 seconds. Comparison between the two settings for Ha images – Unity gain at 300 and 180 seconds – shows that for such a nebulous type of feature as the Rosette, Unity gain works very well at the longer 300 second exposure (first image below) but not 180 seconds (second image below), which is too short to collect sufficient data.

Notwithstanding, in the past I have found shorter exposures at Unity or less have generally been more suitable for brighter objects such as star clusters or galaxies like Andromeda. An alternative SHO Hubble Palette image below of the Rosette Nebula at Unity gain and 300 second exposure also compares more favourably with the same image taken last year using less subs, higher gain and shorter exposure time.

When the object is right, such as the Rosette Nebula, narrowband imaging using the ZWO camera produces exceptional results. This is evident in these recent images where it’s now possible to clearly see structural elements of the nebula, as well as the star fields located within. Frankly I am very excited by these new images and can’t wait for next year to come around again!

When the object is right, such as the Rosette Nebula, narrowband imaging using the ZWO camera produces exceptional results. This is evident in these recent images where it’s now possible to clearly see structural elements of the nebula, as well as the star fields located within. Frankly I am very excited by these new images and can’t wait for next year to come around again!

Postscript: Research at Leeds University just published suggests that the Rosette Nebula is a disc but I believe my eyes and this image and many others which says otherwise!

|

IMAGING DETAILS |

| Object |

Rosette Nebula NGC 2244 + 2237, 2238, 2239 & 2246 |

| Constellation |

Monoceros |

| Distance |

5,000 light-years |

| Size |

Approx. 100 light-years or 1.3o |

| Apparent Magnitude |

+9.0 |

| |

|

| Scope |

William Optics GT81 + Focal Reducer FL 382mm f4.72 |

| Mount |

SW AZ-EQ6 GT + EQASCOM computer control |

| Guiding |

William Optics 50mm guide scope |

| |

+ Starlight Xpress Lodestar X2 guide camera & PHD2 control |

| Camera |

ZWO1600MM-Cool (mono) CMOS sensor |

| |

FOV 2.65o x 2.0o Resolution 2.05”/pix Max. image size 4,656 x 3,520 pix |

| EFW |

ZWOx8 + ZWO LRGB & Ha OIII SII 7nm filters |

| Capture & Processing |

Astro Photography Tool, Deep Sky Stacker & Photoshop CS2 |

| Exposures |

12 x 300 sec Ha, 6 x 300 sec OIII & SII (Total time: 120 minutes) |

| |

@ 139 Gain 21 Offset @ -20oC |

| Calibration |

5 x 300 sec Darks 20 x 1/4000 sec Bias 10 x Flats Ha, OIII & SII @ ADU 25,000 |

| Location & Darkness |

Fairvale Observatory – Redhill – Surrey – UK Typically Bortle 5 |

| Date & Time |

9th February 2018 @ 22.00h |

When the object is right, such as the Rosette Nebula, narrowband imaging using the ZWO camera produces exceptional results. This is evident in these recent images where it’s now possible to clearly see structural elements of the nebula, as well as the star fields located within. Frankly I am very excited by these new images and can’t wait for next year to come around again!

When the object is right, such as the Rosette Nebula, narrowband imaging using the ZWO camera produces exceptional results. This is evident in these recent images where it’s now possible to clearly see structural elements of the nebula, as well as the star fields located within. Frankly I am very excited by these new images and can’t wait for next year to come around again!