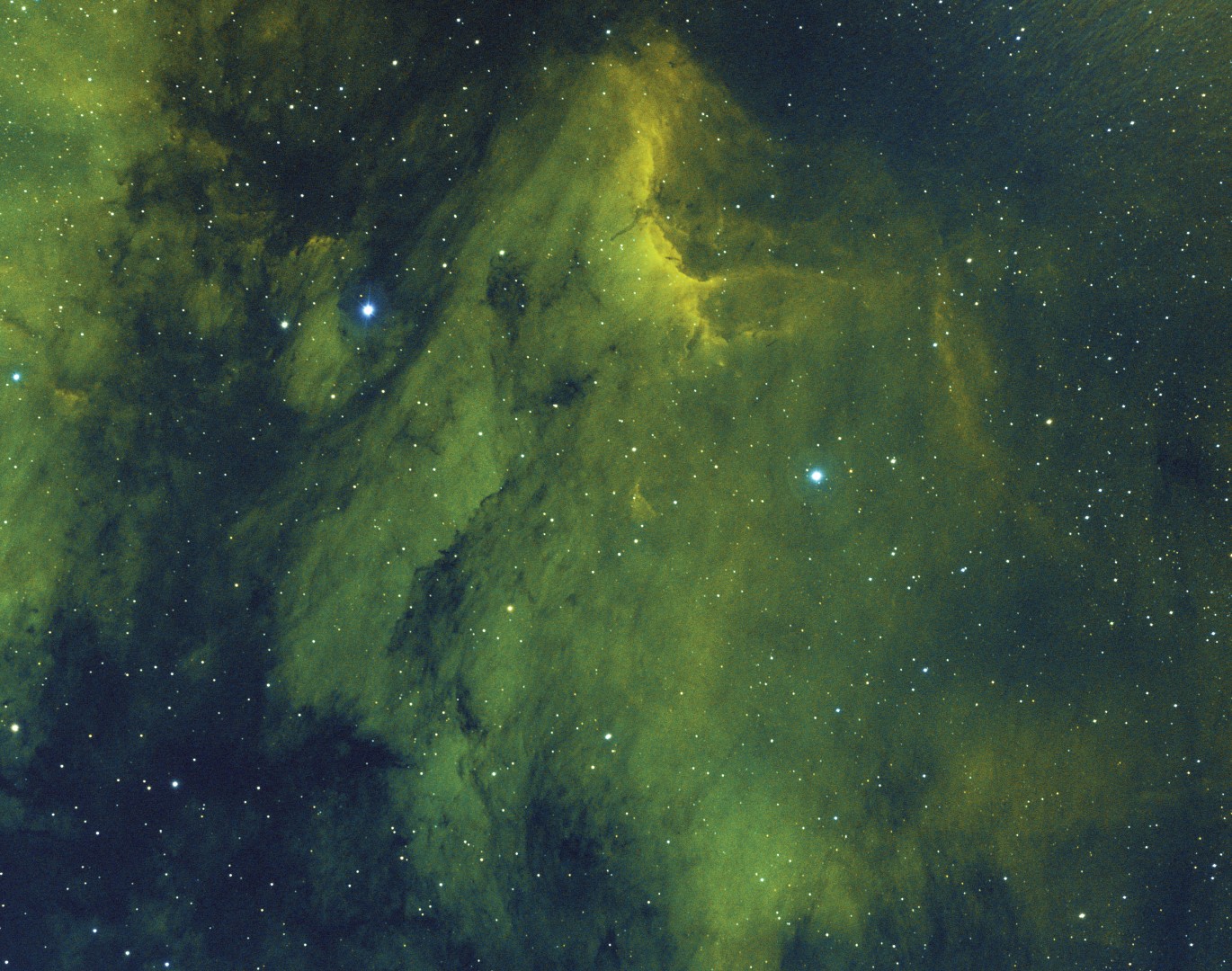

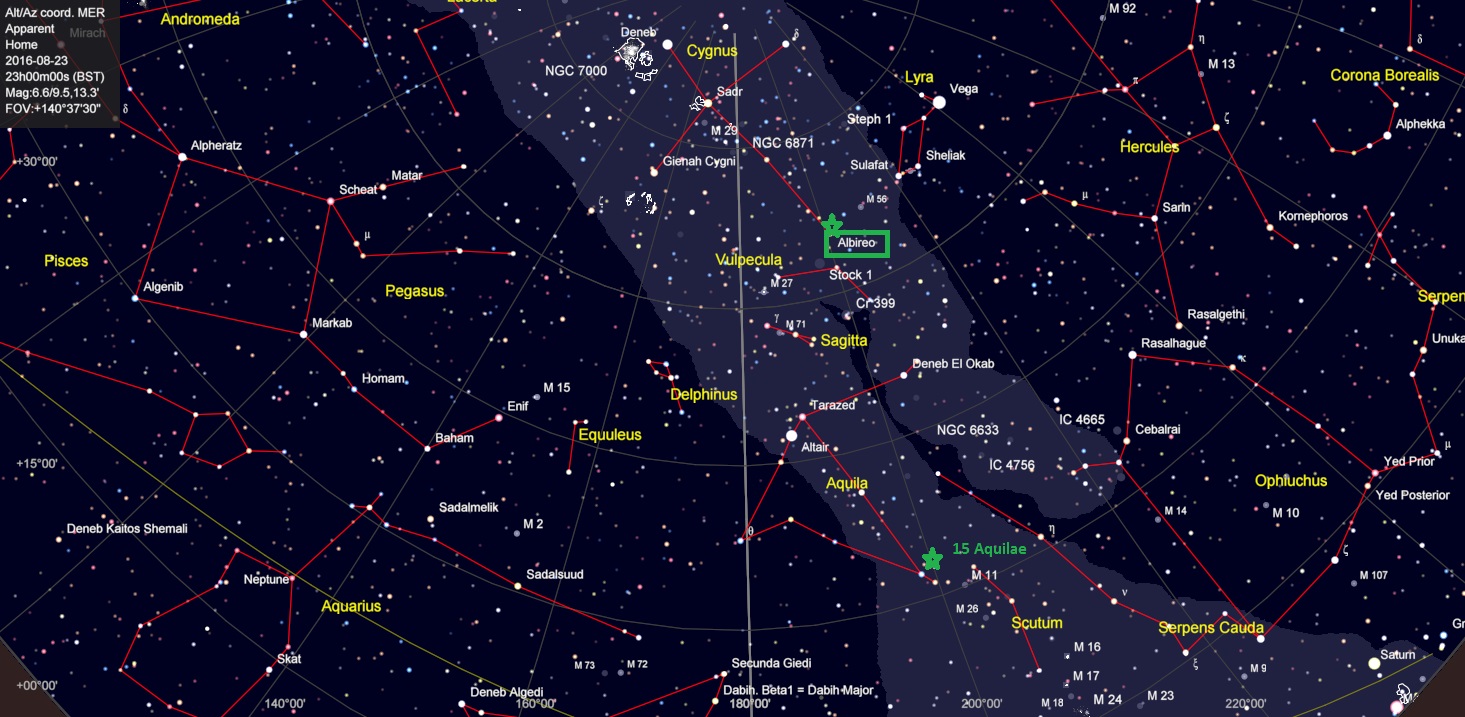

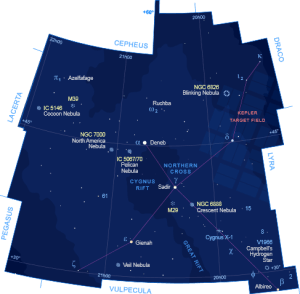

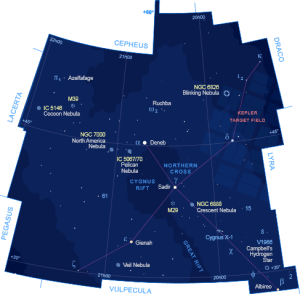

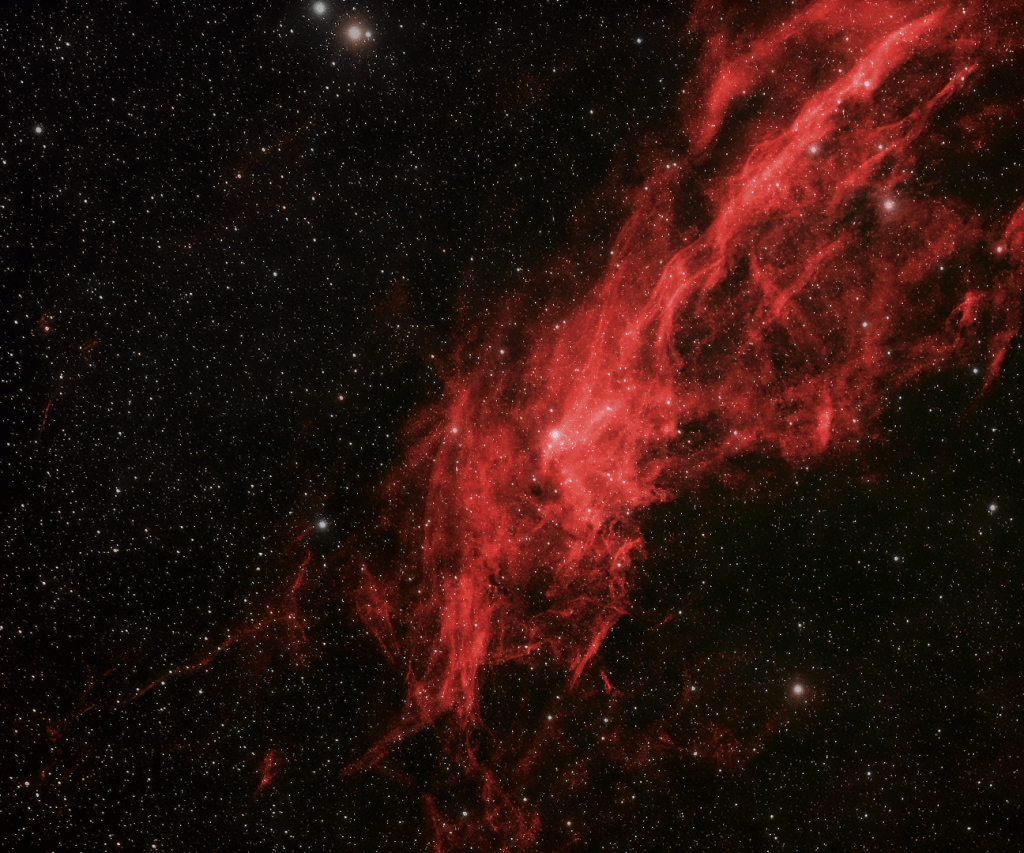

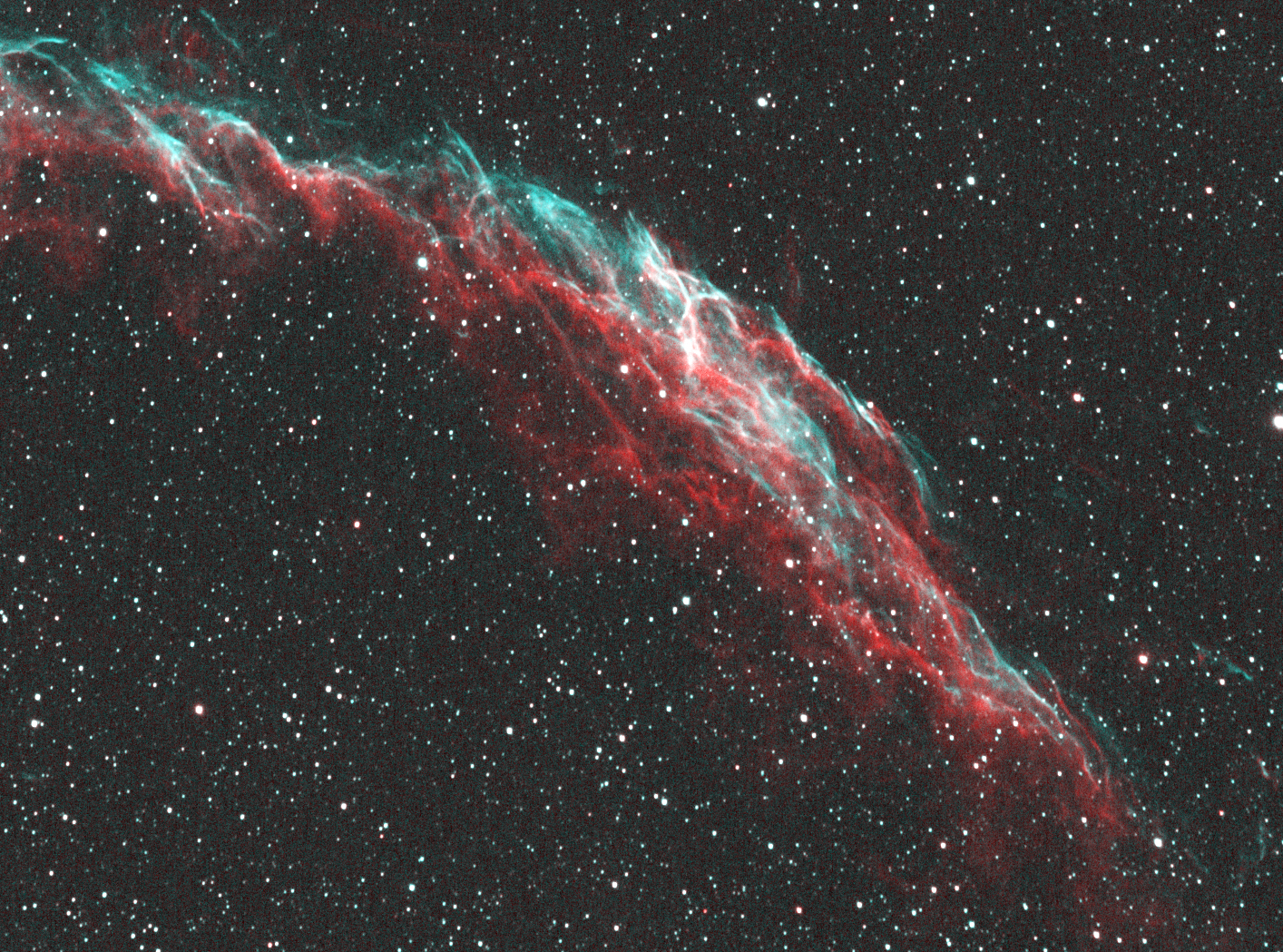

In September I returned to the Cygnus constellation, popular for The North America and Veil Nebula at this time of the year but elsewhere often overlooked by astrophotographers. In particular the vast HII-region that is located around the Deneb-Sadr area which contains an abundance of exciting imaging opportunities, this time my target was LBN325 which contains numerous Ha emission nebulae, a dark nebula and a supernova remnant. To capture these features at their best, I chose to shoot, process and then combine separate HaOO narrowband and RGB images for the first time.

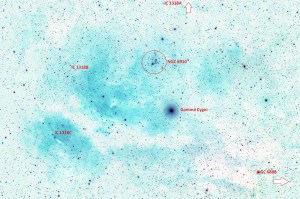

Integrating RGB data for better star colours and narrowband data for nebulosity turned out to be tricky but by removing the stars from the narrowband nebulosity and then processing the starless image before combining with RGB image manually eventually worked out well (see top-of-the-page image). However, the narrowband and broadband data had respectively been taken either side of the Meridian without plate solving and unfortunately my manual alignment was on this occasion poor. However, with careful cropping I was eventually able to able to align and combine each of the images, though at the cost of losing 25% of the overall field-of-view which did not overlap; see full size Ha-image below with interesting features along left and right edges which had to be cropped out to align the final narrowband and broadband images.

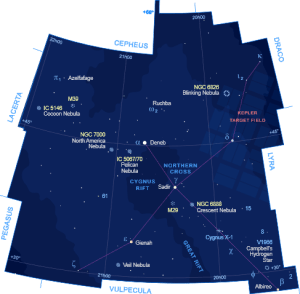

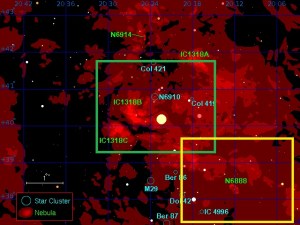

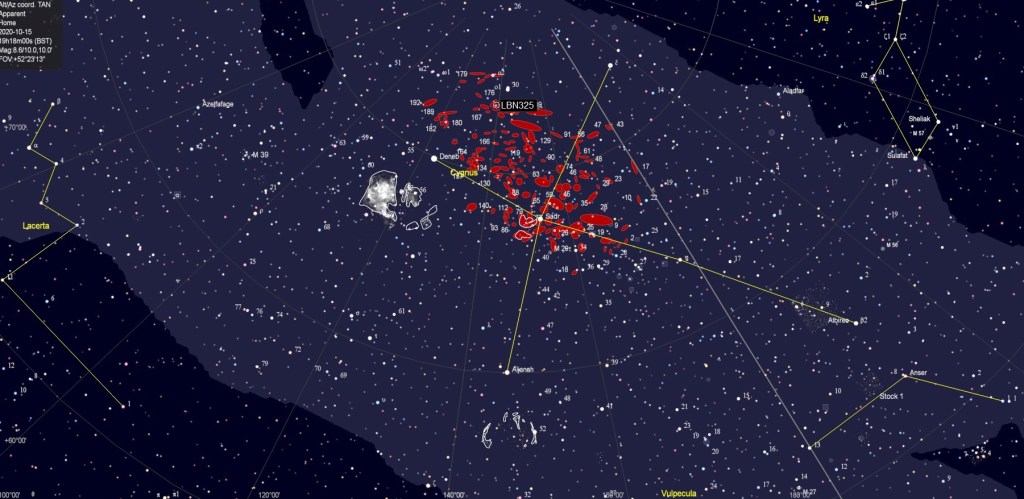

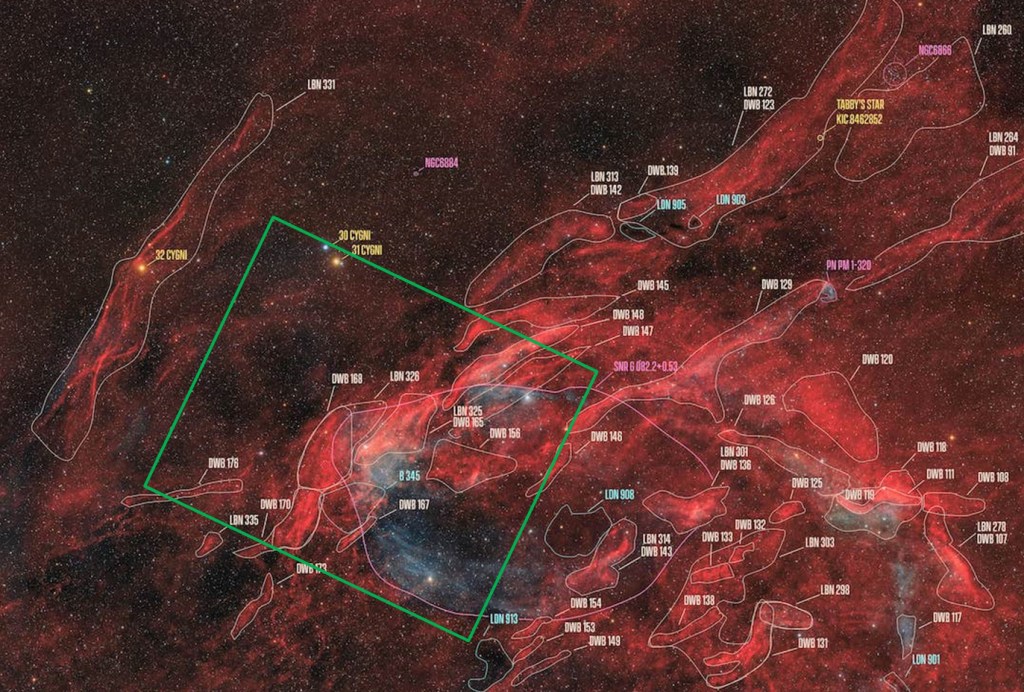

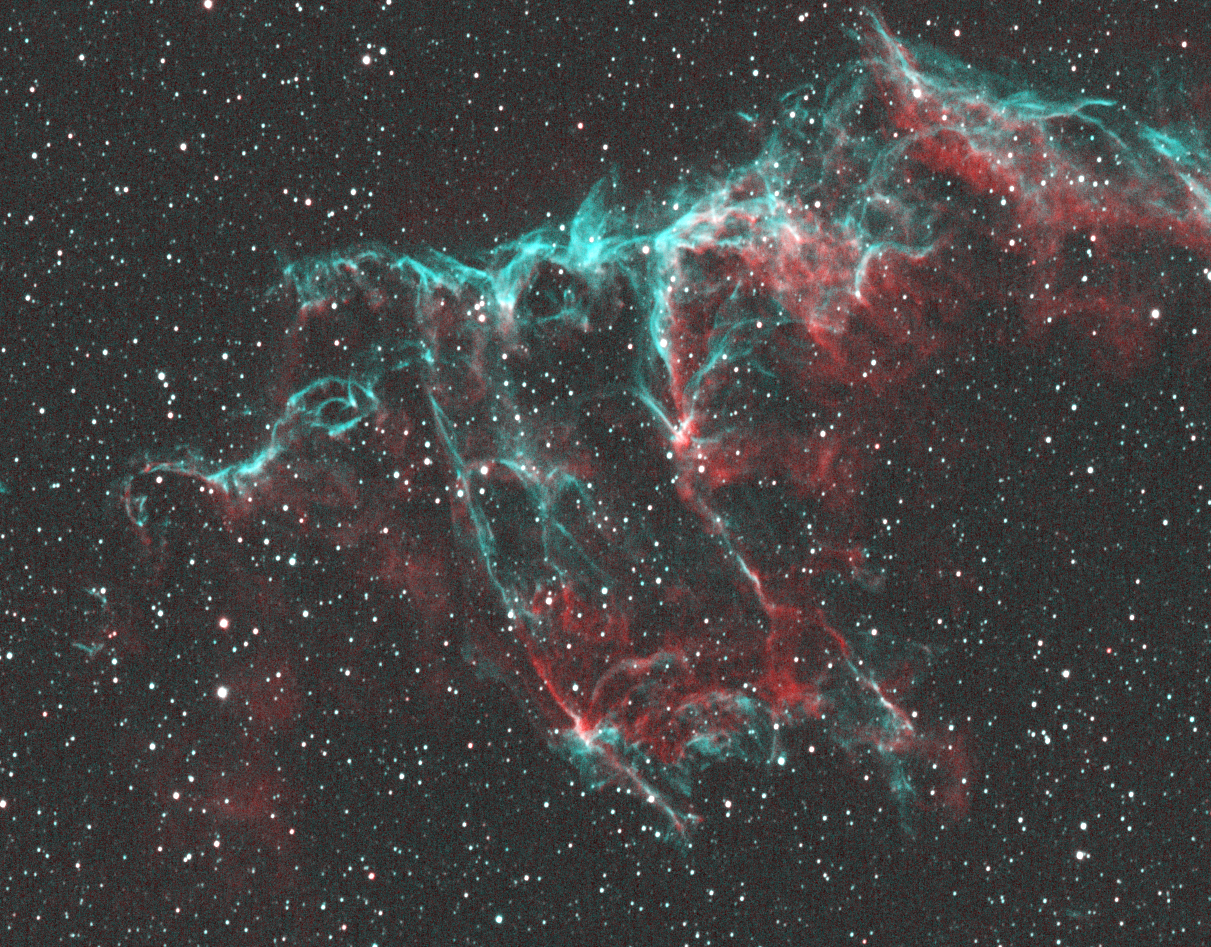

In addition to LBN325 there are a large number of other notable features (see Image Details table at the end & Nico Carver’s annotated image below – green outline delineates areas of my image). In addition to the many Ha emission nebulae, the most noteworthy are the dark nebula Barnard 345 and a large section of the Supernova Remnant G082.2+53. Some 100 light-years in total diameter, this OIII-rich feature is unfortunately too faint to be picked out in my image, which would require significantly more OIII data to be seen. Looking further afield of the image the continuing richness of the adjoining area cannot be overstated, which is beautifully seen in Nico Carver’s accompanying image (Northwestern Cygnus by Nico Carver is licensed under a CC BY-SA 4.0 License) – an 8-pannel 46-hour mosaic! I can only dream of such work but certainly hope to return to this area again when possible, in order to enjoy more of the exquisite objects that can be found across this truly exciting area of Cygnus. But for now there’s another story about this image.

For some time I’ve known that I had to improve my processing skills and to this end purchased PixInsight software at the beginning of the year. Very few of the best astrophotographers do not use this processing software but PixInsight has a notoriously steep learning curve and no doubt like many others I gave up after a few days! I can unequivocally say that PixInsight is by far the most user unfriendly software I’ve come across in nearly four decades; there’s no denying it’s abilities but the developers clearly gave very little thought to its users. Nonetheless, spurred on by the need to improve my images and the ‘opportunity’ of more time that Covid-19 has provided us all recently, I returned to PixInsight a number of times over the summer and slowly made progress.

Using my existing data for M101, I first spent many days working through the calibration and integration process, which can only be described as exhausting! Undeterred and in an effort to speed up matters, I moved on to Batch Processing, which though helpful only partially assists the overall task of pre-processing and inevitably put PixInsight aside again in order to find renewed enthusiasm to continue. From this initial experience I had already come to one conclusion – that I would not be using PixInsight for calibration and integration, continuing for now with Deep Sky Stacker and possibly later switching to either Astro Pixel Processor (APP) or Astro Art, both of which get good user reviews.

From the results of others it’s clear that PixInsight is a route to better images and there is no shortage of online tutorials and books but hitherto I’d not found one that worked well for me. Online tutorials by Light Vortex Astronomy are an excellent learning aid but tricky to work with on screen and Harry’s Astro Shed video tutorials were also helpful but I needed a book on the matter to read, thumb through and casually refer to when needed. Then I got lucky!

It was my good fortune that in May a new text by Rogelio Bernal Andreo (AKA ‘RBA’) Mastering PixInsight became first digitally available and then in September was published as a book. The work is divided into two well thought out and presented volumes:

- A comprehensive, easy-to-follow and understand description of how to use PixInsight

- A reference guide providing more in-depth information on specific PixInsight processes

The two volumes come as a boxed set, are well bound and illustrated and for the first time (from my point-of-view) form an accessible, easy to use and helpful text on PixInsight. RBA deserves every success with this outstanding book(s) which I believe will transform the otherwise torrid experience of learning PixInsight. Armed with RBA’s Mastering PixInsight, Light Vortex Astronomy online tutorials, Harry’s Astro Shed and a other online videos, I’m pleased to say that I am now at last able to use PixInsight for processing and LBN325 is my first image; I should also mention Shawn Nielsen’s excellent Visible Dark YouTube channel, which demonstrates a number of very useful techniques.

As my first attempt to use PixInsight for processing, I’m pleased with the outcome of LBN 325 but realise there’s still much more to learn and, aside from the framing error, it’s clear that even more integration time is needed to get the best of LBN325 and its companions. Going forwards PixInsight and Photoshop both have their respective strengths and weaknesses and judicious use of various techniques from each is probably going to yield the best results. For now, at least, I feel the considerable time put into learning PixInsight is starting to pay off and I’ve finally turned a corner with my processing.

| IMAGING DETAILS | |

| Object | LBN325 & 326 + Barnard 345 & SNR G082.2+5.3 DWB 156, 167, 165, 168, 170, 176, |

| Constellation | Cygnus |

| Distance | 5,000 light-years? |

| Size | >2o |

| Apparent Magnitude | NA |

| Scope | William Optics GT81 + Focal Reducer FL 382mm f4.72 |

| Mount | SW AZ-EQ6 GT + EQASCOM computer control & Cartes du Ciel |

| Guiding | William Optics 50mm guide scope |

| + Starlight Xpress Lodestar X2 camera & PHD2 guiding | |

| Camera | ZWO1600MM-Cool mono CMOS sensor |

| FOV 2.65o x 2.0o Resolution 2.05”/pix Max. image size 4,656 x 3,520 pix | |

| EFW | ZWO x8 + ZWO LRGB & Ha OIII SII 7nm filters |

| Capture & Processing | APT + PHD2 + DSS + PixInsight + Photoshop CS3 + Topaz Denoise AI |

| Image Location | Centre RA 20h 18’ 42.55” DEC +46 25’ 03.12” |

| Exposures | NB 300 sec x 53 Ha & x 38 OIII BB 60 sec x 49 R, x 35 G & x 50 B Time: NB 7hr 58 min BB 2hr 14 min TOTAL 9hr 49 min |

| @ 139 Gain 21 Offset @ -20oC | |

| Calibration | Darks 5 x 300 sec & 10 X 60’ 20 x 1/4000 sec Bias 5 x Ha & OIII Flats 10 x LRGB Flats @ ADU 25,000 |

| Location & Darkness | Fairvale Observatory – Redhill – Surrey – UK Typically Bortle 5-6 |

| Date & Time | 9th 13th & 14th September 2020 @ +21.00h |

| Weather | Approx. 15-20oC RH <=60% 🌙 20% waning |

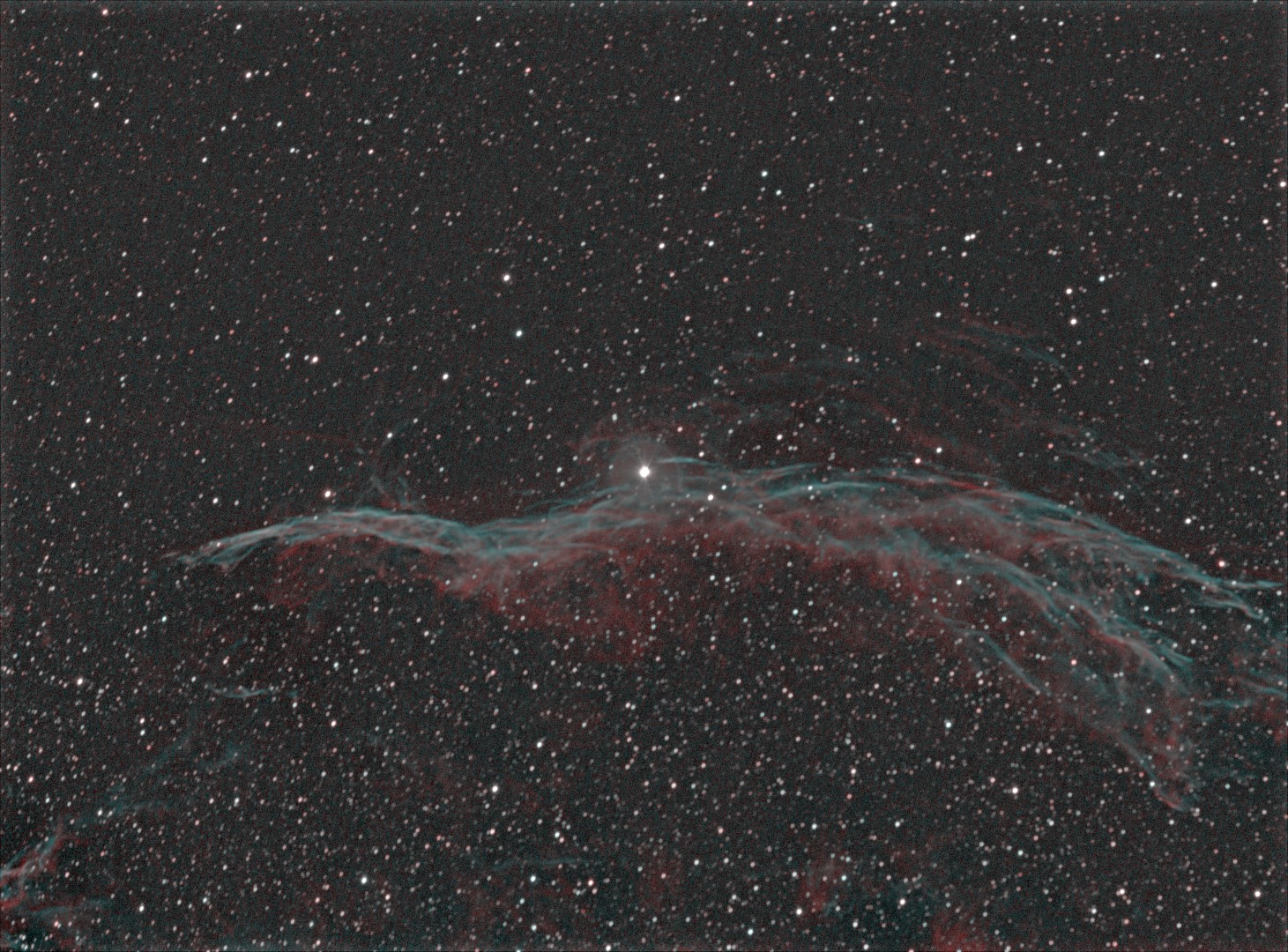

In this case the Ha-image of The Pelican that was obtained demonstrated the significant improvements that can be achieved with the CMOS based ZWO1600MM-Cool camera compared to a DSLR. I’m still learning about processing and in particular, with the plethora of options available when using LRGB and narrowband subs the issues have now escalated exponentially. Notwithstanding the aforementioned issues I’m very pleased with my ‘new’ bird The Pelican Nebula.

In this case the Ha-image of The Pelican that was obtained demonstrated the significant improvements that can be achieved with the CMOS based ZWO1600MM-Cool camera compared to a DSLR. I’m still learning about processing and in particular, with the plethora of options available when using LRGB and narrowband subs the issues have now escalated exponentially. Notwithstanding the aforementioned issues I’m very pleased with my ‘new’ bird The Pelican Nebula.