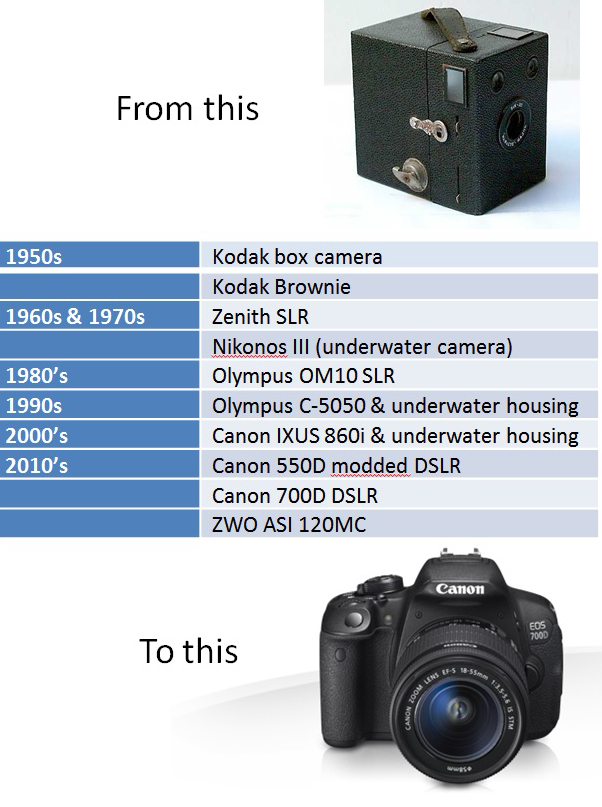

After some months I have just finished reading Walter Isaacson’s outstanding biography of Albert Einstein. I don’t know how the author, as far as I know a scientific layperson and writer of the equally good Steve Jobs biography, is able to pull together Einstein’s thoughts and theories in such an engaging and comprehensible manner that provides both insight and understanding into his scientific thinking, life and personality.

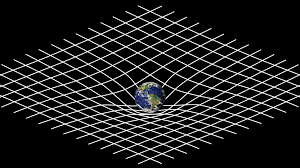

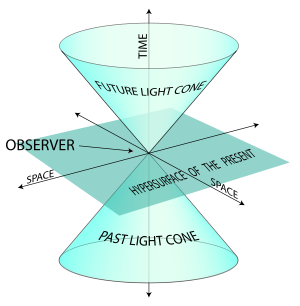

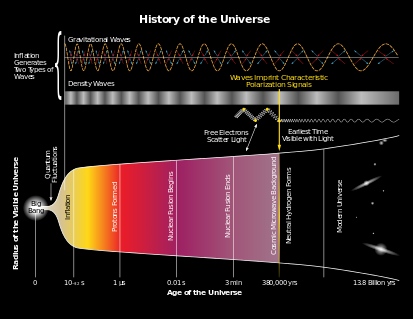

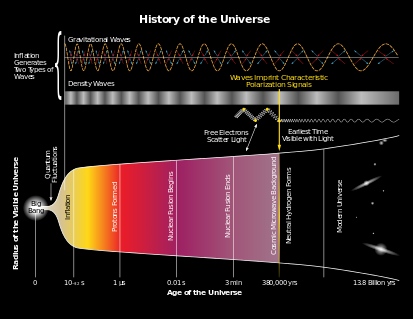

Besides the implications his work already has for nuclear physics and astronomy, even in the 21st Century we are only just starting to understand and confirm concepts that were either predicted or implied by his work of uniquely pioneering theoretical physics in the early part of the last century – much of which is still difficult even to comprehend, let alone understand. In the world of astronomy two of Einstein’s predictions have only recently been shown to actually exist, with very exciting implications for our understanding of the Cosmos: gravitational lensing and earlier this year, confirmation of the presence of gravitational waves – ripples in the fabric of space-time itself!

Einstein vindicated: In the constellation of Cetus, the galaxy cluster Abell 370 abounds with evidence of gravitational lensing – imaged here in 2009 by the Hubble Space Telescope

During his early work Einstein battled with 19th Century scientists who continued to believe in the presence of the so-called ‘aether’, as proposed by Isaac Newton in 1718 – an undefined substance that supposedly filled the void in space and was responsible for the transmission of electromagnetic and gravitational forces. Subsequently Einstein’s Special Theory of Relativity was able to explain such effects without the presence of the aether but there remained problems that were finally borne out in 1924 by Edwin Hubble’s evidence that contrary to the prediction of Einstein’s work and previous astronomical theories, the Universe was in fact expanding. However, though serious these observations did not prove to be the end for Einstein’s work, merely the beginning of even more incredible theories that have even greater and more profound implications for the Universe.

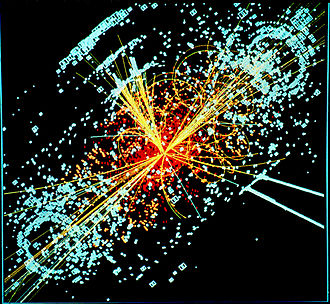

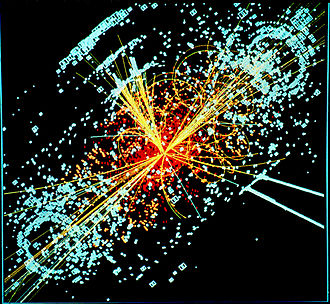

As a geologist by training, my background is scientific and I continue to follow with interest related developments across a broad spectrum. My perception, which I think is justified by facts, is that we are again experiencing something of a quantum change in our understanding of physics at the moment. No ‘new Einstein’ has yet emerged, though Stephen Hawking perhaps comes close and there are many bright minds still struggling to understand what it all means – certainly we seem no closer to a unified theory. At the ‘very small’ scale the increase in particle types since I last studied science in the 1970s is staggering, recently culminating in confirmation of the Higgs boson at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) in Geneva; almost certainly there’s more to come from the LHC but I’ve already lost track (no pun intended) of what makes up matter.

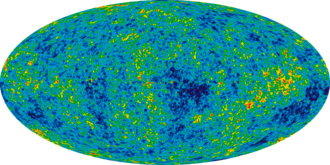

In the meantime, ever since Hubble’s expanding Universe bombshell, the world of physics has struggled to provide an explanation of what’s happening, except to say that for expansion to happen 95% of the Universe must consist of stuff we don’t know about, that is arbitrarily (and misleadingly) called Dark Matter (27%) and Dark Energy (68%), which have theoretical properties of mass and energy that would explain why the Universe is expanding; I find this exciting and even amusing.

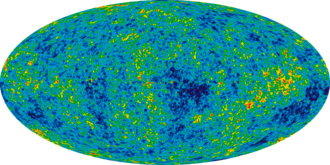

Our earliest view of the Universe – the Cosmic Microwave Background, formed some 380,000 years after Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago.

As I get older I look upon the world with increased wonder and ask all the same big questions as everyone else. I still find science itself exciting as we continue to unlock nature’s wonders but have increasingly had a suspicion that despite the incredible discoveries made by mankind, we are really only scratching the surface of what’s going on. The prospect that there is still so much we do not know also provides many possibilities for what is really happening; a consoling thought as I move towards old age! I believe it’s humbling for science that they (we) only know what 5% of what the Universe is made of. Notwithstanding, like Deep Thought’s answer to the question “what’s the meaning of life the Universe and everything?” in Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (answer = 42), it will keep thousands of scientists, their computers and the media gainfully employed for many years to come. In the meantime, perhaps I can already help them?

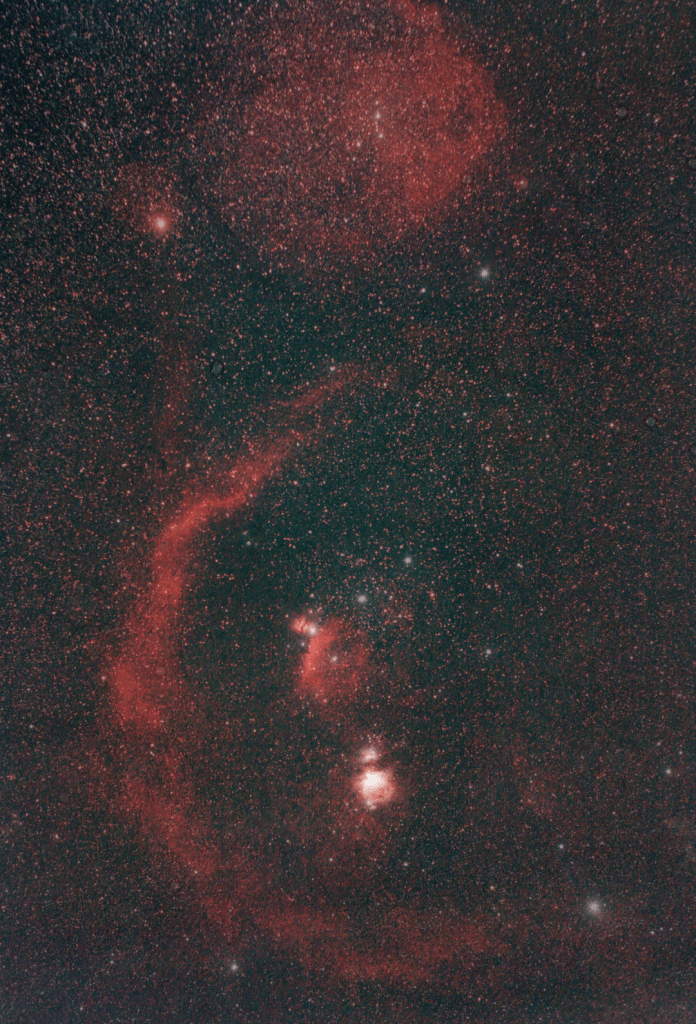

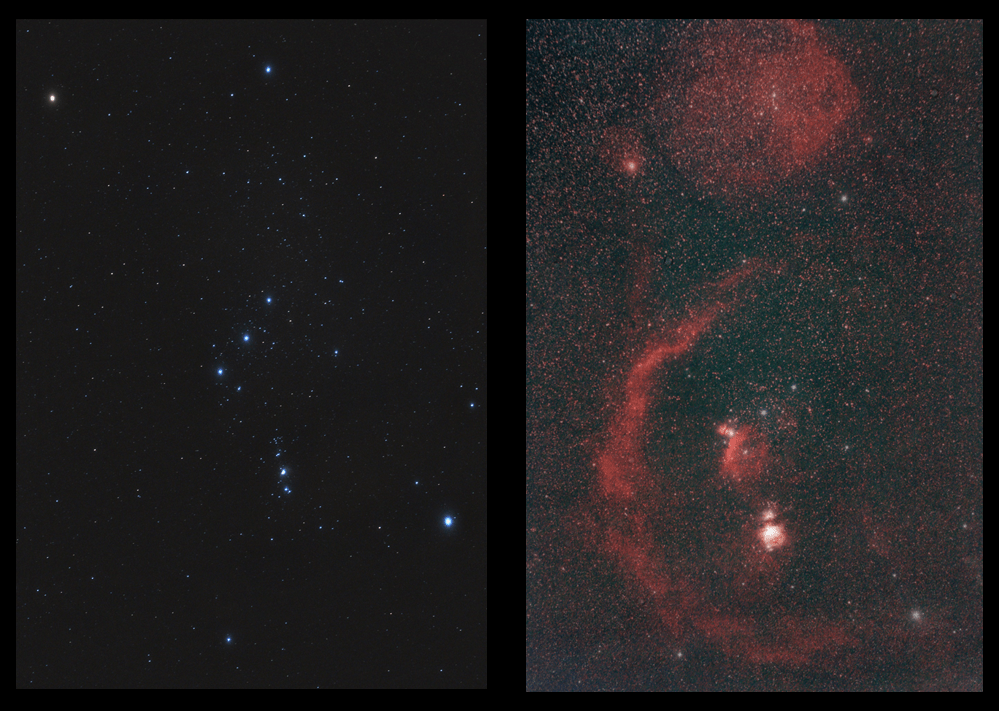

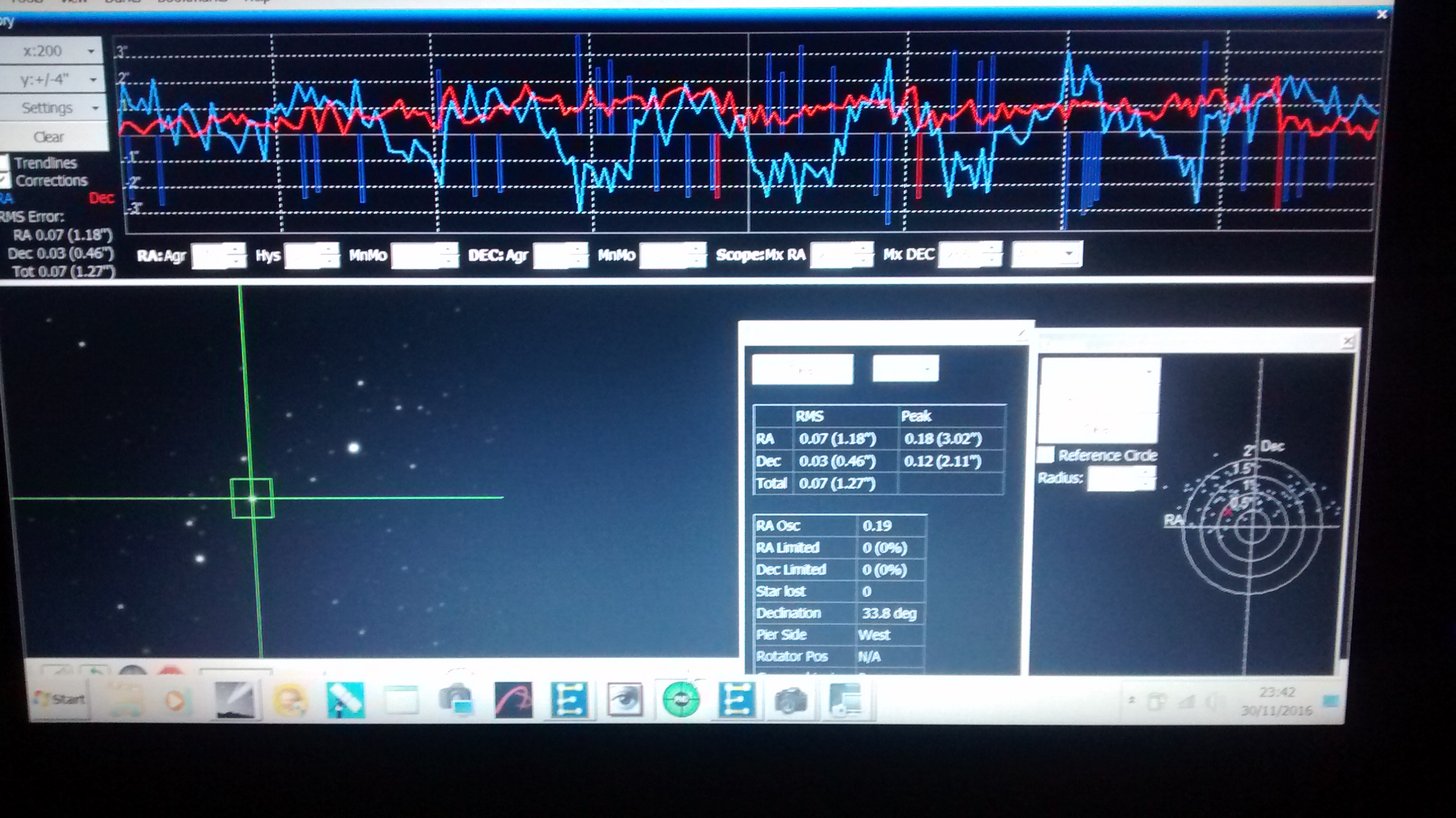

Early on in my astroimaging odyssey I discovered an interest in Deep Sky Objects, in particular nebulae. I find their very nature beautiful, as the birthplace of new stars and matter itself their science is also fascinating – as Moby puts it We Are All Made of Stars. There are numerous types of nebulae of equally diverse origin, with a complex variety of delicate forms that can be both enthralling and beguiling. Generally they are made of gases and dust that emit types of light that often cannot be properly seen with the naked eye and only captured by photographic methods using various sophisticated imaging techniques, such as modified cameras or narrow band filters; their very elusiveness is part of the attraction. I have been fortunate to photograph a number of these features and never get tired of their science and beauty. However, there are other types of nebulae that are quite different.

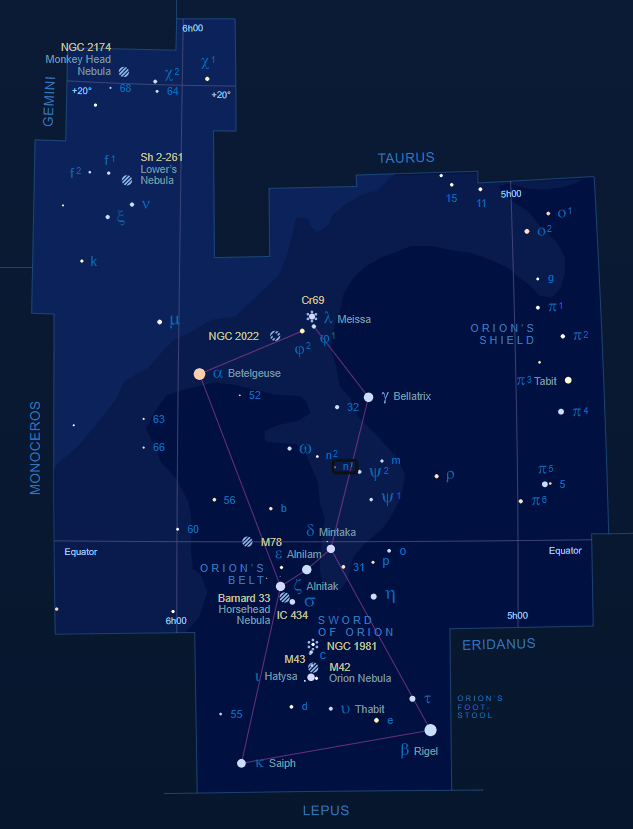

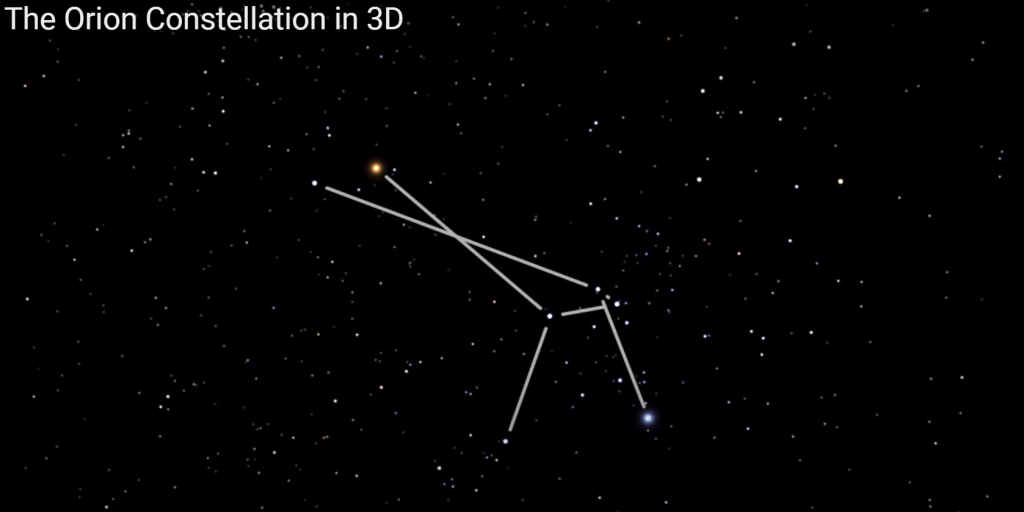

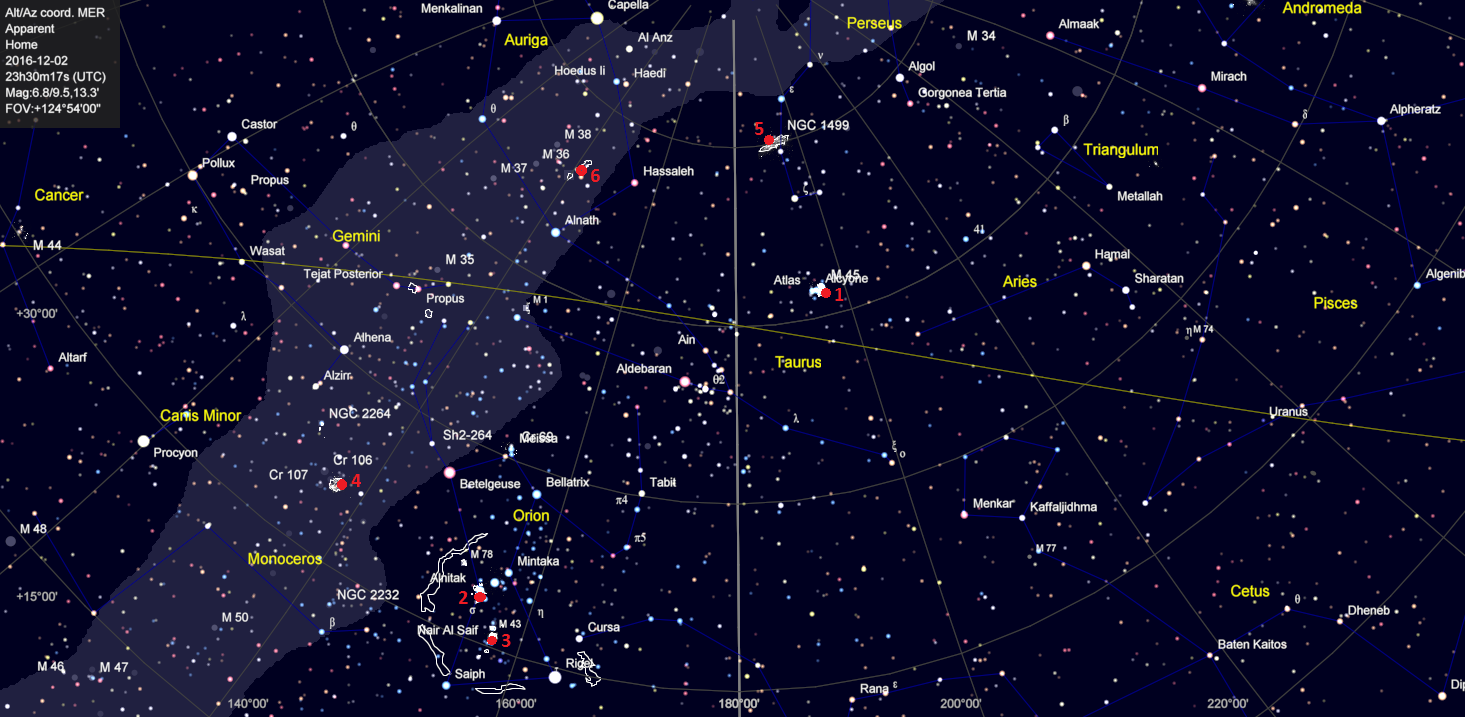

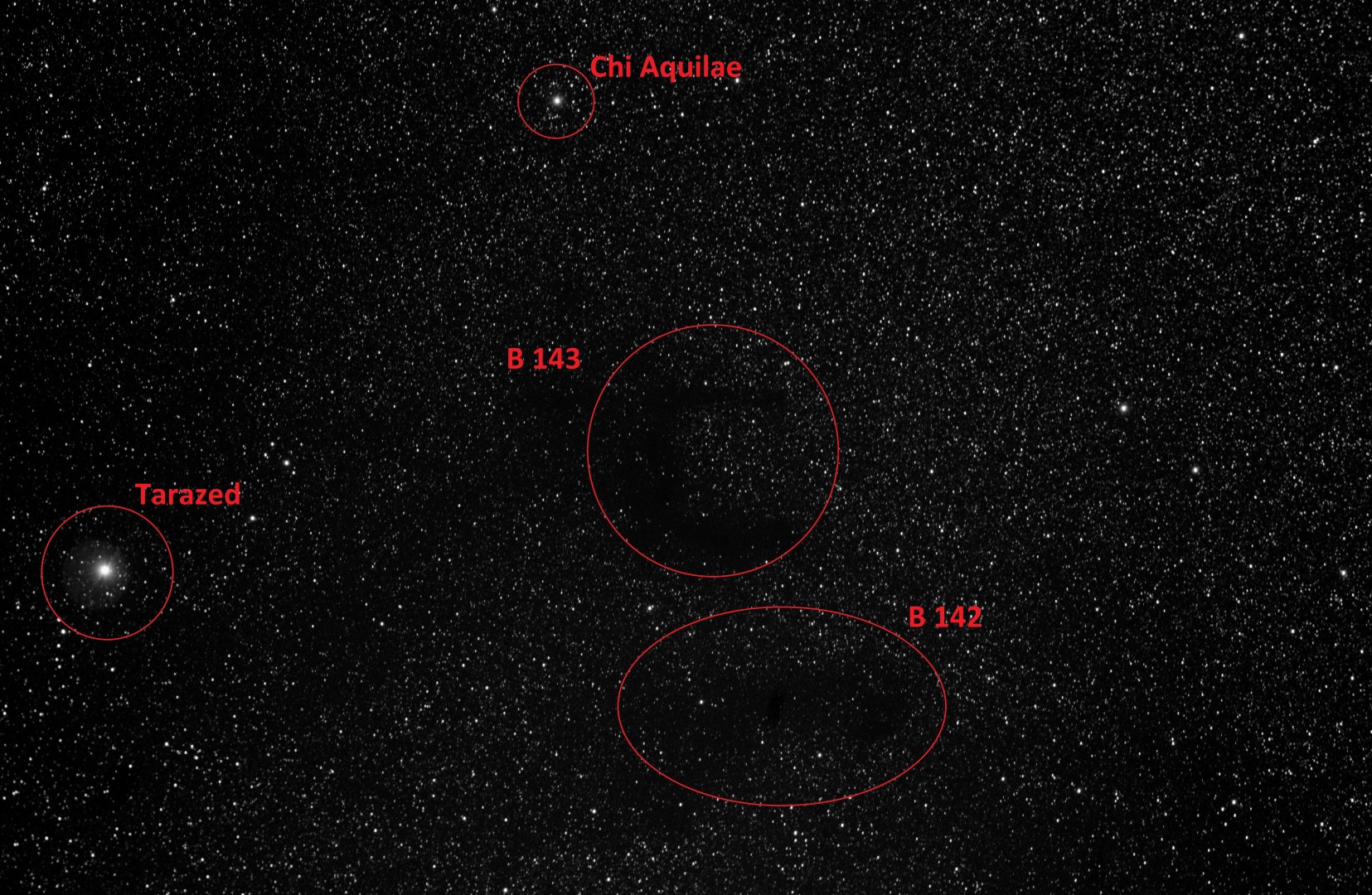

Whereas the ‘common’ nebula is fundamentally based on activity that results in the emission or reflection of light, their other ‘ relations’ are the result of a quite opposite process. In this case so-called dark or absorption nebulae are clouds of dense interstellar dust that obscures or scatters light from nearby objects behind, such as stars or emission and reflection nebulae, resulting in large, unusually dark patches in the sky. I’ve imaged a few of these features before, where in the case of Orion such a process has produced Barnard 33, better known as the Horsehead Nebula – a dark interstellar dust region in the shape of yes, a horse’s head. Recently I set out to image another less famous but equally exciting dark nebula.

Other than resorting to solar astronomy, the period of summer sometimes seems like something of a barren period, further compounded by short nights and the absence of astronomical darkness. Notwithstanding, look closely and there’s plenty happening and, if you’re lucky, it’s possible to work into the night enjoying the warmth of the season too; I’ve recently been able to stay out in a shorts and T-shirt until past 3.00 a.m. – compare that to January – apart from the comfort there’s also no sign of the astronomer’s enemy, dew. This year my wife has grown and strategically placed two night flowering plants close to my equipment, which on warm evenings produce pleasant aromas that waft across Fairvale Observatory whilst I’m working. What’s not to like?

Night Phlox (Zaluzianskya Capensis). Though quite this small plant produces a strong smell of violets at night.

Nicotiana Alata. This large plant produces a strong, fragrant smell.

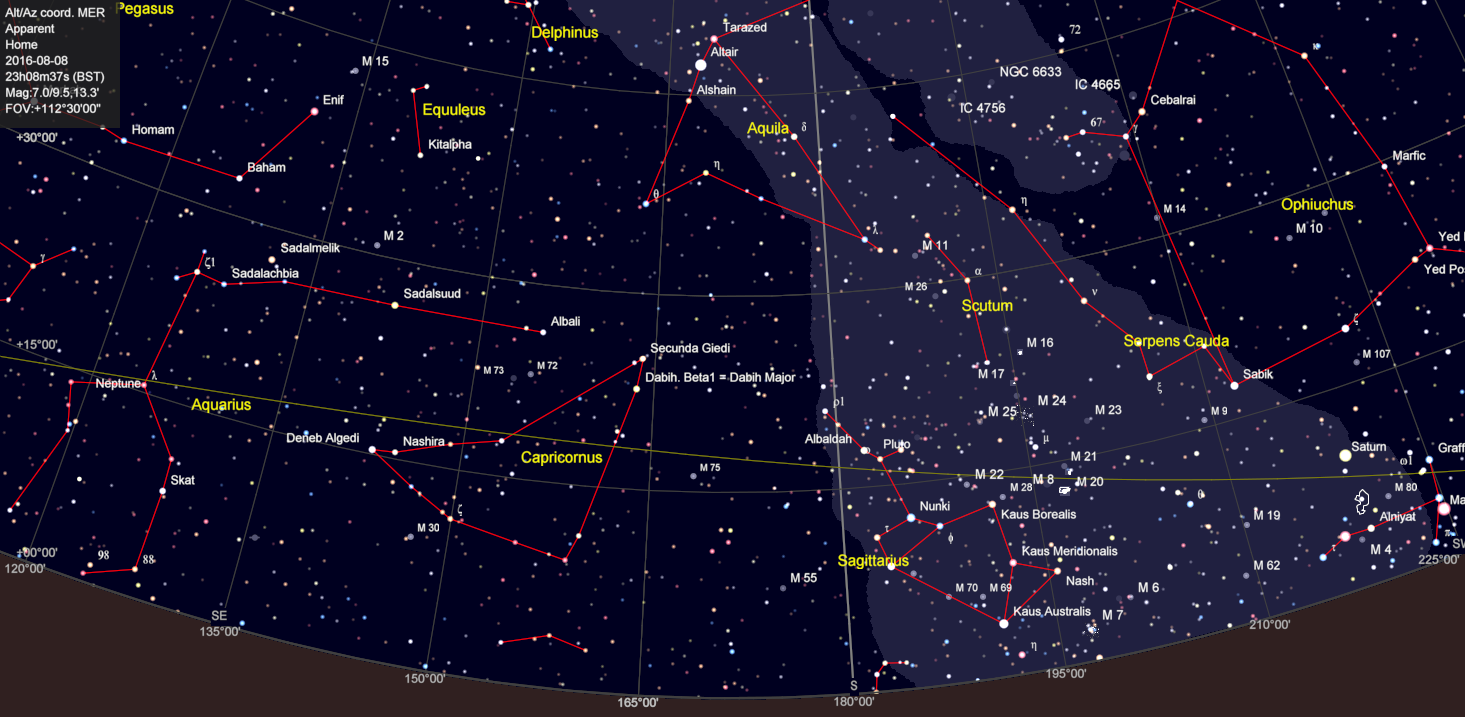

Whilst there’s no Orion (though it has made an appearance in the east from at about 3.00 a.m. since late August) or Taurus (also rising shortly before Orion) with all their iconic features, instead the summer arm of the Milky Way passes across the sky from about 8.00 p.m. presenting numerous opportunities of its own in the early part of the night.

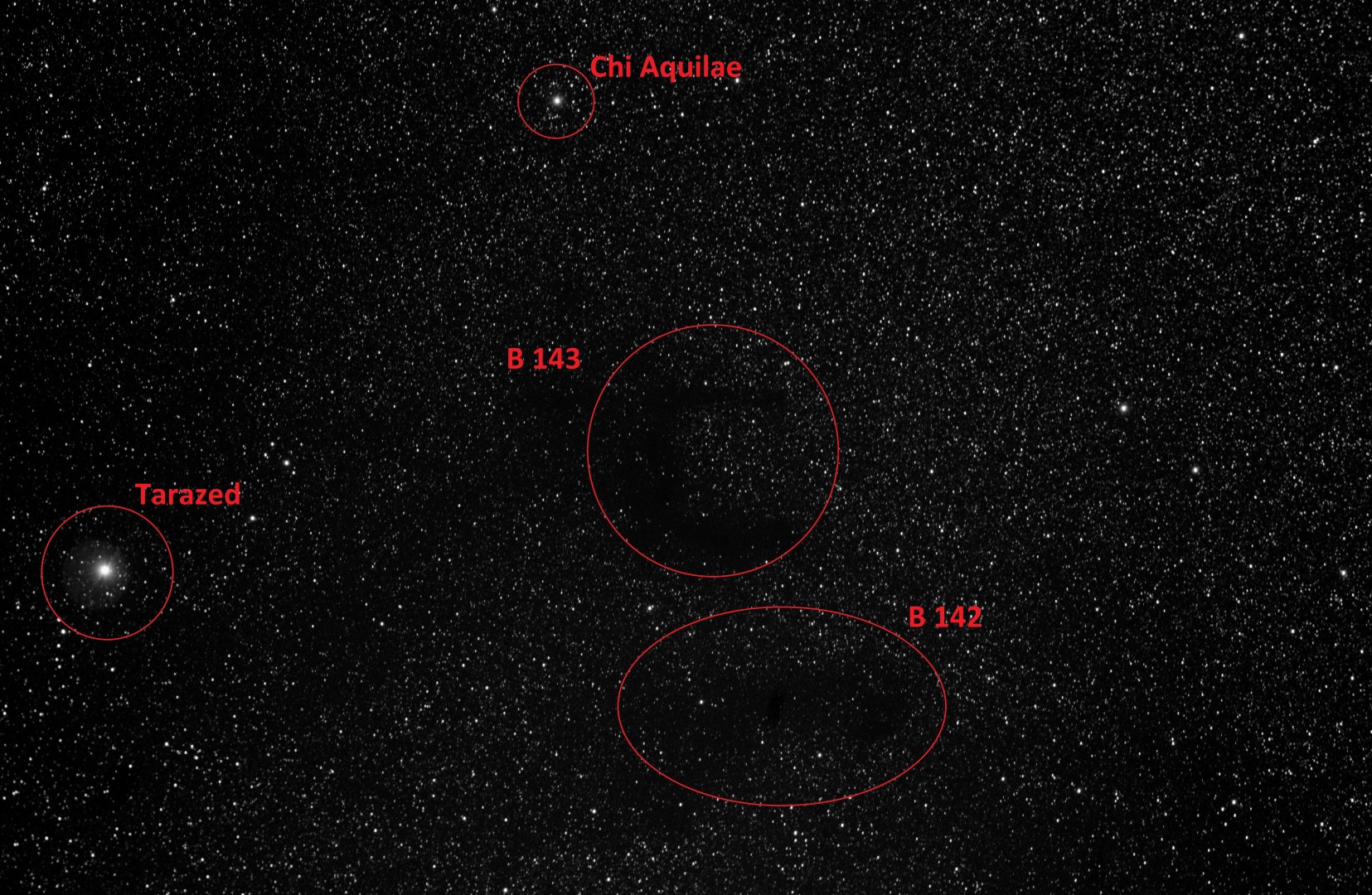

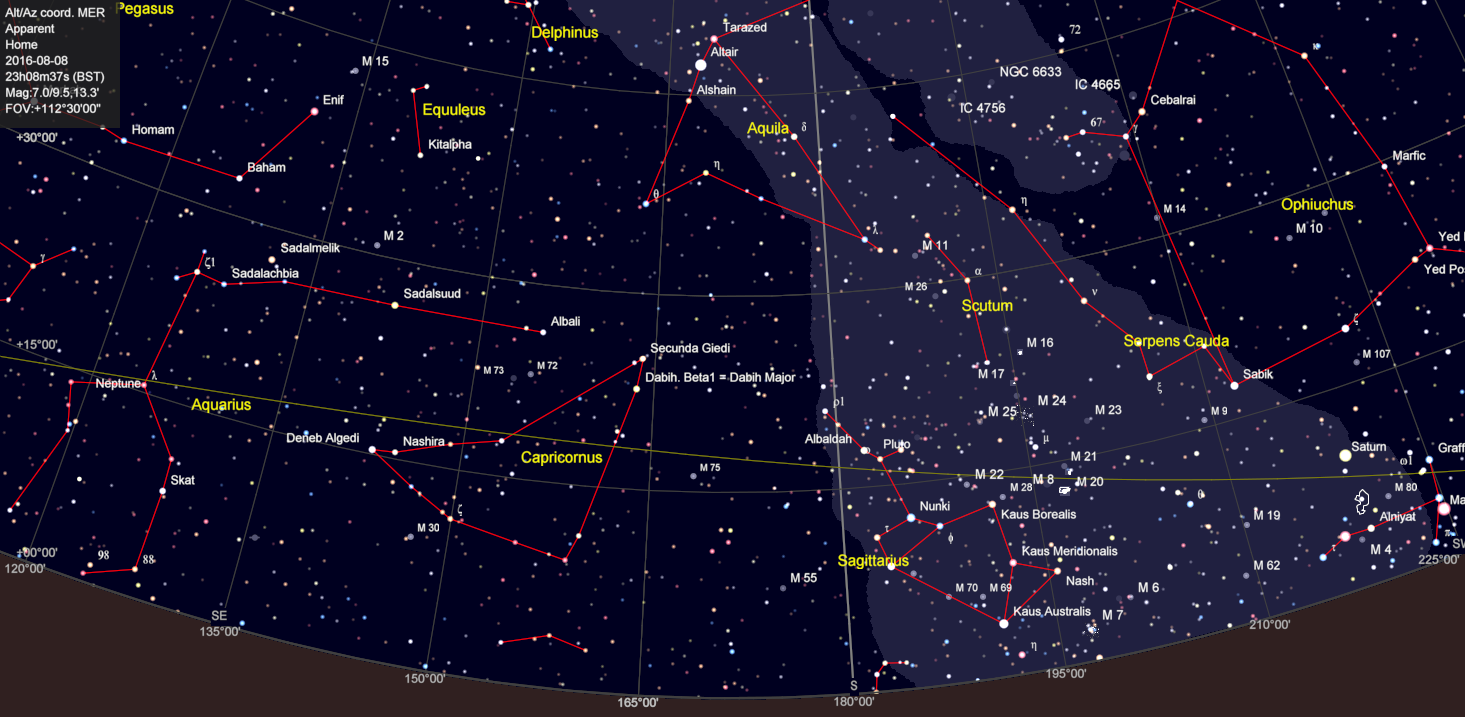

This time my targets were Barnard 142 & 143, located just west of the star Tarazed in the Aquila Constellation. Roughly equivalent to the full Moon in size distance and some 2,000 light years away, both are dark nebulae which viewed together against the dense background of stars in the Milky Way clearly make the shape of the letter E – shown first below in inverted colour.

Previously I’ve been too busy looking for the more conventional DSOs but at some 30 arc minutes, the E Nebula – as it is known – is another excellent imaging target for the William Optics GT81 field-of-view.

It turns out there are many such dark nebulae, so I hope to be imaging others in the future. I wonder what Einstein would have made of these and moreover, the hypothesis of Dark Matter & Energy? It seems that once again he may have foreseen such developments and their possible existence may ironically even be found to relate to the cosmological constant used in his original General Theory of Relativity.