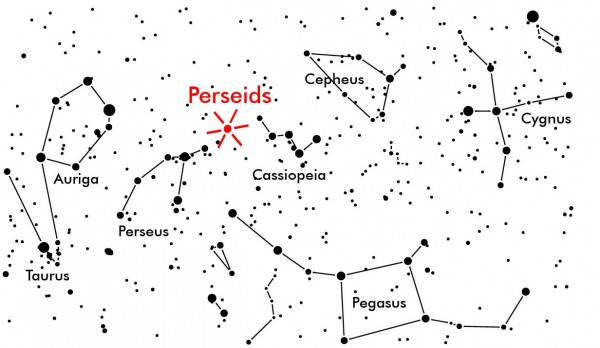

It’s that time of the year when Earth ploughs its way through the tail of comet Swift-Tuttle, resulting in a the Perseids meteor shower. The name is derived from the location of the radiant point within the constellation of Perseus and Greek mythology’s reference to the sons of Perseus. Such are the orbital paths that Earth’s encounter with the comet occurs around 11th to 13th of August each year and can provide an enjoyable spectacle as the meteor particles rain down through atmosphere.

Travelling at some 37 miles-a-second, the sand-grain size particles literally burn up in the blink of an eye, with the energy created producing a bright path of the light path that very briefly shoots across the night sky, sometimes green or red coloured. Some 16-miles in size, from time-to-time the comet itself actually passes nearby to Earth during its orbit around the Sun, last time being in 1992 and the next in 2126.

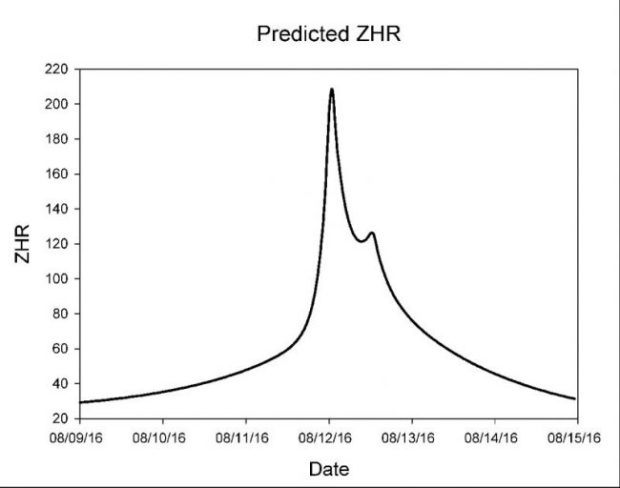

Whilst the timing of our annual encounter can be predicted with good accuracy, a sight of each individual meteoroid particle is entirely down to chance. Over a period of two or three days the frequency (Zenithal Hourly Rate or ZHR) may vary from a few tens to a few hundred, depending on which section of the comet’s tail Earth is passing through. Of course, observation requires a clear sky – something that’s been notably absent here at Fairvale Observatory for some time now. Notwithstanding, this year there were three consecutive clear, dark, warm nights, which occurred shortly after a new Moon that provided excellent Perseid observing opportunities.

Viewing is a matter of lying back in a suitable garden chair looking up towards the radiant position, which starts in the north east then moves to the south during the night and just waiting. This year peak Perseids were on the evening of 11th/12th August between about 11pm and 1am, during which time we probably saw between 20 to 40 hits an hour; the previous and subsequent evenings were also quite good, though with slightly less hits. Such is the randomness of each meteoroid hit that in practice Perseid trails occurred all over the sky and were easy to miss if outside the peripheral vision. However, overall it was a very good and enjoyable show but probably not as good as that from the ISS.

At first this looks great but look again, it’s an aircraft trace – living next to Gatwick airport doesn’t help. The giveaway is in the next shot which shows the track continuing i.e. too long and too far for a meteoroid.

At the same time using the Canon DSLR and an ultra-wide lens, I also attempted to image the Perseid shower. On the first night using Vixen Polarie tracking, set towards the radiant position and on the second night pointing east, without tracking. Control was via an intervalometer, with camera settings at ISO 800, 20 or 14 second exposures, and 5-second shot intervals. Even with such a high incidence of meteoroid hits, obtaining a photograph was still very difficult; mostly the strikes occurred outside the field-of-vision or sometimes in the 5-second pause. In total I shot over 300 images but obtained just two Perseid hits and more than a few plane tracks! Even with good preparation and clear skies it really is a case of chance but I was nonetheless pleased to have my share of luck this time and look forwards to another opportunity this time next year, weather permitting.

Gotcha – the real thing: ISO 800 @ 20 seconds with tracking.

Only just! This time the Perseid is just sneaking out of view at the bottom of the frame: ISO 800 @ 14 seconds, without tracking.