I’ve been interested in photography from a young age. As I child I played with my parent’s Kodak box camera and, as far as I can remember, my first camera was a Kodak Brownie at the age of about nine. It’s a wonderful medium that I have now experienced for over 50-years, on land, underwater and now for astrophotography.

My cameras

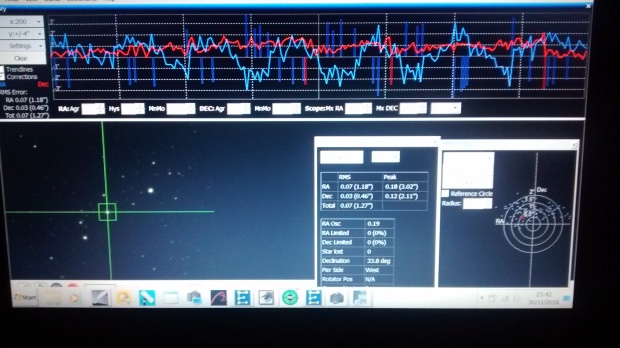

I’d like to think I know a thing or two about photography by now; underwater photography and digital astrophotography have been particularly challenging in different ways but the latter is a real eye opener that has expanded my knowledge of digital imaging significantly. Capturing images of distant objects that can only be seen with the use of sophisticated equipment and complex processing also requires an in-depth understanding of light itself.

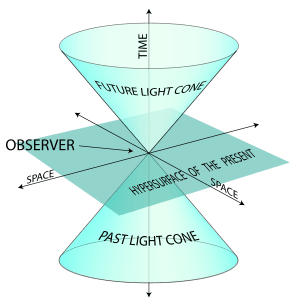

Having spent the first half of this year reading Einstein’s biography, I have recently started an online course at Stanford University on his ground-breaking Special Theory of Relativity. Einstein’s many insights into the physical world are profound, which more than 100-years on still challenge most of us to understand. Light was at the core of his famous 1905 paper, in particular it’s duality as a waveform and light quanta, or photons – defined as a quantum of electromagnetic radiation. His concept of the photoelectric effect has enabled the development of today’s digital camera sensors and CCDs. The core principal is the production of electrons as light shines onto a material, whereby the light (photon) knocks out an electron which can then be collected electronically – the basis of digital photography.

In September I visited Lacock Abbey in Wiltshire, initially a 13th century nunnery which is now run by the National Trust. Today it is better known as the home of William Henry Fox Talbot (1800 – 1877) – mathematician, astronomer and archaeologist but most famously the inventor and pioneer of photography, notably developing, fixing and printing. The window photograph below (left) was taken at Lacock Abbey in August 1835 and is recognised as being from the oldest ever camera negative produced by Fox Talbot, on the right is the same window in 2016.

In the early 19th century Thomas Wedgwood had made photograms – silhouettes of leaves and other objects – but these faded quickly. In 1827, Joseph Nicéphore de Niepce produced pictures on bitumen, and in January 1839, Louis Daguerre displayed his ‘Daguerreotypes’ – pictures on silver plates – to the French Academy of Sciences. Three weeks later, Fox Talbot reported his ‘art of photogenic drawing’ to the Royal Society, which subsequently became the de facto basis of modern film photography.

Fox Talbot’s desk in his study at Lacock Abbey

Fox Talbot lived and worked at the Abbey for most of his life. As well as an excellent museum, which details the history of photography and photographic processes, the house contains his rooms where he developed (no pun intended) the aforementioned inventions and is surely a ‘must do’ visit for any keen photographer. Like many at that time he was a polymath, with notable friends and accomplices who worked in similar and other scientific fields:

Sir John Herschel – astronomer, mathematician, botanist & chemist, Gold Medal winner and founder of the Royal Astronomical Society, son of William Herschel who discovered Uranus.

Charles Babbage – mathematician, philosopher, mechanical engineer, considered “the father of the computer”;

William Whewell – leading 19th century scientist, recognised in the fields of architecture, mechanics, mineralogy, moral philosophy, astronomy, political economy, and the philosophy of science;

Sir Charles Wheatstone – physicist, inventor of stereoscopic photography, the telegraph & accordion;

Sir David Brewster – physicist specialising in optics, mathematician, astronomer & inventor of optical mineralogy and the kaleidoscope;

Peter Roget – physician, theologian, lexicographer and publisher of Roget’s Thesarus.

This particular group are now remembered by a table setting in the Abbey’s dining room, where they gathered for dinner; the mind boggles at the conversation!

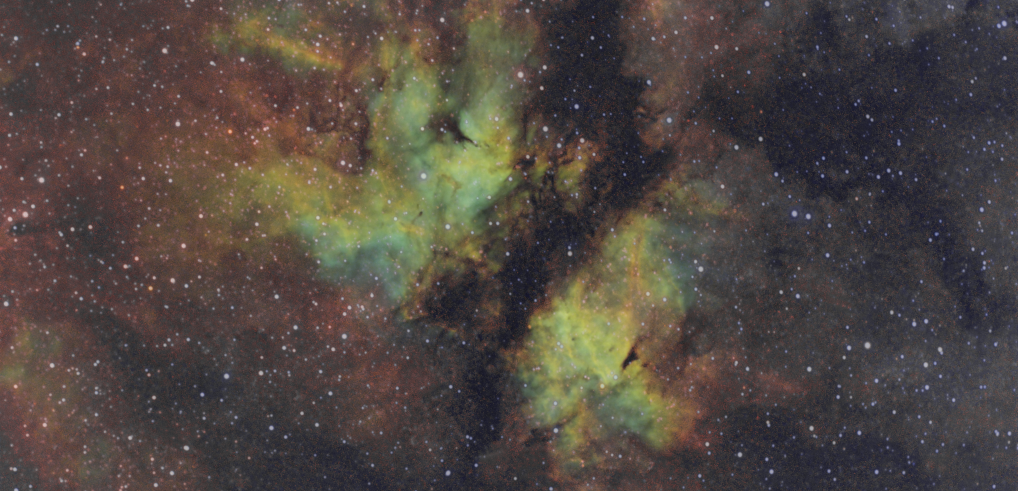

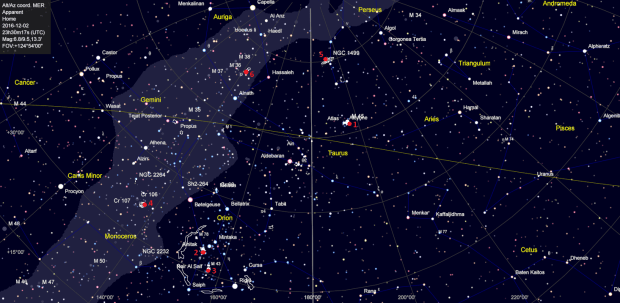

Fox Talbot’s pioneering photography work preceded the early 20th century understanding of light that arose from Einstein and its more recent application in semi-conductors as camera sensors, of which I am sure he would have approved. At that time the Universe outside of our galaxy was also unknown and he would have marvelled further at the thought of imaging other such distant galaxies such as M33 below; like photons, photography has come a long way since his death in 1877.

M33 Triangulum Galaxy – consisting of some 40-billion stars, the photons in this image have travelled 3-million light years to reach my camera’s sensor! | WO GT81 + modded Canon EOS 550D & FF guided | 18 x 300 secs @ ISO 800 & full calibration | 22nd October 2016