After 24-weeks I have just completed Imagining Other Earths, a Coursera MOOC presented by David Spergel, Charles A. Young Professor of Astronomy at Princeton University – soon to become Director of the new Computational Centre of Astrophysics, NY – and cannot speak too highly of the course. In my quest to better understand what I am seeing and imaging, I have participated in five astronomy courses and this is by a country mile the best; how many country miles in a parsec I wonder? There was very little not covered about astronomy in the course, including related geology and life itself but it was outstanding for three reasons:

- Frequent use of easy-to-understand equations to explain and link various processes responsible for the Universe and everything in it;

- It is very comprehensive, thorough and well produced, and…

- David’s lecturing is just very good – easy to understand and well delivered.

For some while now the trend in my astrophotography has been increasingly directed towards seeing the big picture and by coincidence the course followed a similar scientific theme in order to Imagine Other Earths throughout the Universe; a metaphor for life itself and possibilities across the Universe.

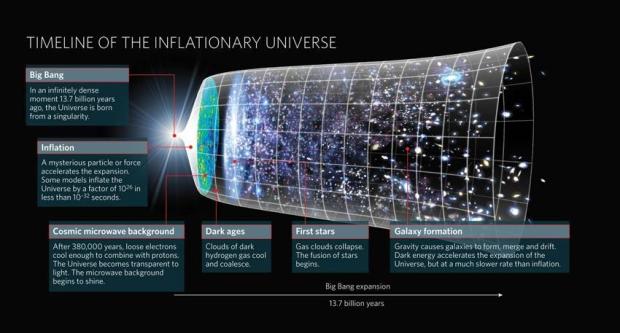

The ultimate question starts at the beginning – where do we come from? Moby and astrophysicists seem to have the answer: we are all made of stars. How we get from that to here may be an even bigger question and like the philosophers in The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy looking for the meaning of life (answer = 42!), should keep many astrophysicists gainfully employed for aeons.

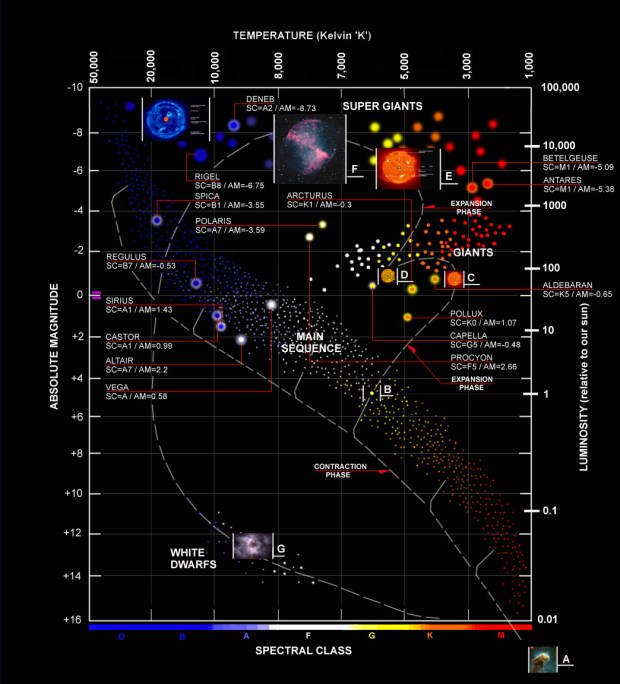

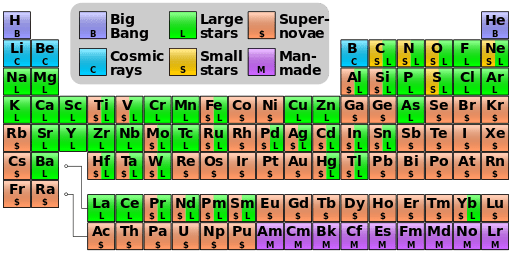

In the meantime there is strong evidence that we do indeed come from stars and their evolution through the process of nucleosynthesis, which is responsible for all but a few man-made elements that we find on Earth. Through the action of nuclear fusion a star burns its way through the periodic table, first from hydrogen to helium then carbon-oxygen-magnesium-silicon and eventually iron. Thereafter the other, heavier elements require even more extreme conditions – heat & pressure – that can only be found in the late or final stage of a star’s life such as a Super Nova.

When the Periodic Table was initially formulated in 1863 by Dimitri Mendeleev there were 53 elements, which through subsequent discovery have now grown to 118. I find it wonderful and exciting that almost all of these can be attributed to stellar evolution, which can be viewed and imaged in the night sky.

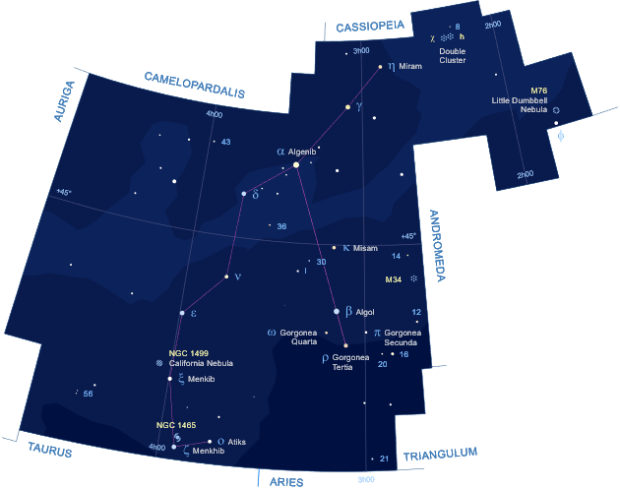

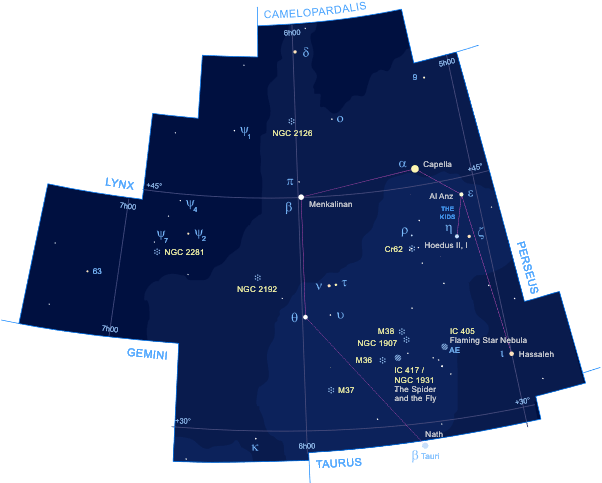

At this time of the year the Milky Way is a dominant feature passing across the winter night sky which provides numerous, sometimes spectacular objects that are favourable for imaging. Located close to the western edge of the Milky Way in the constellation of Auriga about 1,500 light-years from Earth, is IC 405 or Flaming Star Nebula and nearby (visually) IC 410 or Tadpole Nebula, itself at 12,000 light-years distance. Located across the central area between these objects is a star field, notable of which and actually within the IC 405 is the O-type blue variable star of AE Aurigae, that is responsible for illuminating the nebulae.

IC 405 is formed of two sections, consisting of an emission and reflection nebula. Radiation from the variable star AE Aurigea, that is located in the lower part of upper-east (left) lobe, excites the hydrogen gas of the nebula which then glows red, while carbon-rich dust also creates a blue reflection from the same star.

IC 405 (right)-The Flaming Star Nebula inc AE Aurigae varibale star & IC 405-The Tadpole Nebula: WO GT81 & modded Canon 550D + FF | 15 x 180 sec @ ISO 1,600 & full calibration | 8th December 2015

Located within the nebula IC 410 and partly responsible for its illumination is an open cluster of massive young stars, NGC 1893. Being just 4-million years old these bright star clusters are the site of new star formation and therefore are just starting their creation of new elements. The so named ‘tadpoles’ are filaments of cool gas and dust about 10 light-years long.

IC 410-The Tadpole Nebula: Illuminated from within by the NGC 1839 star cluster. Image cropped and forced to highlight the two ‘tadpoles’, which can just be seen indicated in the green ellipses (‘tails’ upwards)

Each nebula is large, respectively 30’ x 20’ and 40’ x 30’, with an apparent magnitude of +6.0, which combined with the star AE Aurigae makes an excellent target for the William Optics GT81. I find it thrilling to consider the processes taking place in these objects that I have captured in the photograph, which surely represents the ultimate Big Picture?